No More Drug War Demands Sydney, as Berejiklian Drags Her Feet on Solutions

The 17th of June next year marks the 50th anniversary of the day on which US president Richard Nixon declared the war on drugs.

Marking an intensification of then half-a-century-old global drug prohibition, this gung-ho approach to a health issue has destroyed countless lives ever since.

Comprised of former heads of state and leading intellectuals, the Global Commission on Drug Policy released a 2011 report, marking the 40th anniversary. It asserted, “The global war on drugs has failed”.

Indeed, rather than erase them, the war has escalated drug use, availability, strength and their harms.

It’s in the shadow of this vast edifice that drug decriminalisation advocates gathered before Sydney’s Town Hall on Sunday to call out the “Just Say No” Berejiklian government’s latest fumbling of the ball on this issue.

The Coalition knows too well that something needs to change in terms of this state’s tired drug war policies. The NSW government has established an expert panel followed by a special commission all to ignore any progressive recommendations that Nixon would have frowned upon.

The 13 December No More Drug War rally was calling out today’s meeting of the Berejiklian cabinet, in which it plans to deliberate upon an approach to dealing with personal drug possession even more diminished than the already weakened depenalisation scheme it flagged two weeks ago.

A feeble approach

“The NSW government is going to make a decision. And we can already tell it’s going to be a seriously watered-down decision from the recommendations of the ice inquiry,” NSW Greens MLC David Shoebridge told those gathered.

“We know that because we’ve seen the right-wing of the Liberal Party launch attack after attack in the Daily Telegraph just because there was a suggestion, which had a small slither of rational changes to drug laws.”

The backlash Shoebridge was referring to involved the response that prehistoric Liberal and National politicians had to Berejiklian’s original depenalisation approach that would have seen those caught with a personal amount of drugs initially warned, then twice fined, prior to any charges being laid.

This was after the government-established Special Commission of Inquiry Into the Drug Ice recommended full decriminalisation, meaning no charges whatsoever. Veteran drug law reformer Dr Alex Wodak last week described depenalisation as a “very minimal” response to the inquiry.

However, Shoebridge explained that NSW police has now forced a change to the original proposal so the scheme being debated today will involve an initial fine, followed by two more fines within the same 24 month period, with a fourth finding of personal possession resulting in charges being laid.

The scheme will also involve mandatory drug rehabilitation for those found in possession of illicit substances for personal use. The fines could be as steep as $1,000. And there might also be a dob in your dealer clause, meaning those who turn in someone else could receive reduced penalties.

The Greens justice spokesperson outlined that this scheme is designed with middleclass kids in mind who can afford to be fined a couple of times at festivals without facing charges, while First Nations youths and young people of colour being overpoliced will eventually receive charges.

“Begging for a new approach”

“Unlike most other places in Australia, NSW does not have a drug and alcohol strategy,” said NUAA chief executive Mary Ellen Harrod. She added that the state did develop a strategy quite recently, which she was involved in, however the government has conveniently buried it.

According to Harrod, this most likely occurred as the strategy was founded in harm minimisation: supply, demand and harm reduction. “There is actually no place in harm minimisation for targeting users, but that’s our government’s preferred response,” she made clear.

NUAA (NSW Users and AIDS Association) was formed in the mid-1980s. Promoting the health and rights of people who use drugs, NUAA’s first task was distributing safe injecting equipment to people who inject drugs at the time the HIV/AIDS crisis was emerging.

Now president of the Australian Drug Law Reform Foundation, Dr Wodak was pivotal in bringing about the rollout of needle and syringe exchanges. And by the time Sydney established the King’s Cross medically supervised injecting centre in 2001, NSW was a world leader in harm minimisation.

“Our government’s current drug and alcohol strategy is one of ‘just say no’,” Harrod continued. “We know it doesn’t work. What ‘just say no’ is telling people is that if you experience harm, it’s your fault. You made that choice, and it’s your fault.”

The tireless harm reduction advocate maintained that what’s needed is a greater focus on the actual 109 recommendations of the official inquiry into ice, which saw those speaking at the hearings “literally, begging for a new approach to drug use in NSW”.

The end is nigh

“The people who have drug or alcohol afflictions have health problems. They should be treated as health problems,” explained Nathan Moran, chief of the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council. “In our culture, we certainly treat them as health problems.”

Rather than investing in more criminal justice solutions, Moran suggested that “a better return” would come from investment in “health, culture and identity”. And he stressed that, “It breaks my heart and my community’s in seeing so many of our mob locked away for their health problems.”

Along with Shoebridge and NUUA, the No More Drug War protest was hosted by Students for Sensible Drug Policy, the NSW Young Greens and the Sniff Off campaign.

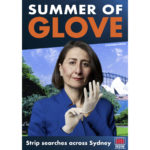

Moving into its tenth year in operation, Sniff Off is calling for an end to the warrantless use of drug dogs in public places, as well as an end to strip searches being applied in relation to turning up small amounts of drugs for personal use.

“First Nations communities and young people of colour in western Sydney are the ones who are going to get fine, fine, fine and then straight to court. Nothing will change for those communities who need the greatest relief from overpolicing and drug dogs,” Shoebridge concluded.

“That’s why we’re calling out these pretend changes for what they are. They won’t work. They won’t end the war on drugs. And we need to go much further than what’s being proposed. We need to decriminalise drugs across the board.”