Prison Guards Alleged to Have Kept ‘Trophies’ of Aboriginal Deaths In Custody

Amongst some of the more distressing malpractices raised by the recent NSW parliamentary inquiry into First Nations overincarceration and custodial deaths are allegations of a “trophy culture” existing within Corrective Services NSW (CSNSW).

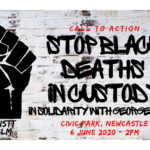

Initiated by NSW MLC David Shoebridge, the inquiry was sparked by last year’s huge Black Lives Matter protests.

Indeed, the Greens member told the Sydney 2021 Invasion Day rally that he couldn’t have established the select committee without the on-the-street mobilisations of mid-2020.

The inquiry held its final hearings last December, and it will be delivering its findings on 15 April this year, which will mark the 30th anniversary of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody handing down its final report.

The trophy culture suggestions involve certain prison guards having partaken in a practice where trophies linked to the death of an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander inmate – such as an item of their clothing or jewellery – are taken as some sort of macabre souvenir.

Trophies are awarded in the community for positive achievement. While the taking of trophies is most often associated with soldiers picking up items from the bodies of enemy troops. And both these aspects of what a trophy signifies reveals a serious prejudice within correctives culture.

Institutionalised malice

“The inquiry received an array of distressing evidence from family members and former inmates,” Shoebridge explained. “It suggests there’s a so-called trophy culture in place, where souvenirs are being taken by Corrective Services staff, including instances where inmates have died in custody.”

“It’s been difficult within the inquiry process to fully test these allegations,” he told Sydney Criminal Lawyers. “But they’re so disturbing that they further support the case for independent review of all deaths in custody.”

Since 1991, there have been over 440 First Nations deaths within the custody of either Australian police or corrections. These deaths are always put down to being accidents or suicides. And until very recently, a charge of murder has never been levelled against a police officer in relation to one.

In the case of corrective services, no officer has ever been charged with murder. However, in a national first, a NSW prison guard was charged this month with manslaughter for allegedly shooting Wiradjuri man Dwayne Johnstone in the back as he ran away whilst handcuffed and shackled.

Shoebridge added that the concept of a trophy culture operating against this backdrop is “sickening”, and, along with all the other evidence of systemic racism coming out of the inquiry, no First Nations family member can feel confident that their loved one is protected on the inside.

Identified and ignored

The Royal Commission Into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody handed down its final report in 1991. It made 339 recommendations, most of which have never been acted upon.

Take recommendation number 165. It states that within prisons and police stations there’s essential equipment that may have the potential to cause harm or self-harm to inmates. So, in the case of hanging points, these should be screened to eliminate the ability to use them.

The July 2020 coronial inquest into the 2017 death of Tane Chatfield in hospital following an incident in Tamworth prison, found that the 22-year-old Gamilaraay, Gumbaynggirr and Wakka Wakka man had taken his own life using a prominent hanging point in the cell he was detained within.

NSW state coroner Harriet Grahame recommended that CSNSW conduct an audit with the aim of removing hanging points from cells. She also found that a CSNSW staff member citing Tamworth prison’s heritage listing as a barrier to removing points as being “entirely inadequate” reasoning.

One of the chief investigators on the Deathscapes project Professor Joseph Pugliese recently explained that he’d attended the inquest into the death of David Dungay Junior, and many of the malpractices involved in that incident resulted from not having implemented the recommendations.

Dungay died in the hospital ward of Long Bay gaol in December 2015, whilst he was being held face down in the prone position by five corrections officers, some of whom were kneeling on his back, as he repeatedly called out that he was unable to breathe.

A toxic culture

Shoebridge added that the trophy culture allegations, and others like it, that emerged from the inquiry are hardly the first “examples of a disturbingly aggressive and racist culture amongst some of Corrective Services”.

The Greens justice spokesperson pointed to The Last Governor Facebook page, which “has been routinely distributing vile and inappropriate messages amongst current and former Corrective Services officers”. And he questioned why CSNSW management has done nothing to put a stop to it.

And further questions around the culture within Corrective Service were raised in the press last year, as former female staff members explained that they’d had to resign after being subjected to sustained campaigns of sexual harassment, discrimination and bullying.

Calls for independent inquiries

The NSW Select Committee on the High Level of First Nations People in Custody and Oversight and Review of Deaths in Custody received 132 submissions, many of which were from Aboriginal-led organisations and legal services, as well as some from the families of deaths in custody victims.

Being delivered on the Royal Commission’s 30th anniversary, the aim is to ensure that the current inquiry recommendations will be implemented in a post Black Lives Matter setting, which involves a vocal First Nations movement and a growing acknowledgement of the need for truth-telling.

Shoebridge maintained that one of the most prominent needs to come out of the inquiry is for the establishment of an independent body to investigate First Nations custodial deaths, as the current system is designed to be opaque with CSNSW in charge of inquiries and crime scenes.

In its submission to the inquiry, the National Justice Project outlined that in the case of David Dungay’s death, a forensic inspection of the scene was not possible as the cell had been cleaned, against protocol, prior to any investigations taking place.

“In an environment where the organisation that’s potentially culpable has complete control of the crime scene, the evidence and witness statements,” Shoebridge concluded, “you can see why no First Nations family would ever have confidence in the outcome under the current system.”