Public Drunkenness Laws Must Be Repealed

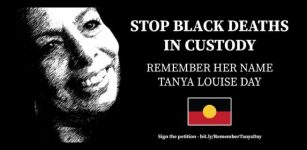

Tanya Day was asleep on a train from Bendigo bound for Melbourne on 5 December 2017, when a V/Line conductor woke her up and asked for her ticket. Disorientated, as she’d been drinking that day, the 55-year-old mother couldn’t find it.

So, the ticket inspector called the police. Officers then arrested the Yorta Yorta woman for public drunkenness at Castlemaine station and took her to the local police station, where they put her in a watchhouse cell to “sober up” at around 3.50 pm.

Whilst in the cell, Ms Day fell and hit her head at least four times during the initial two hours she was held in custody. CCTV footage shows that at 4.50 pm she fell and hit her forehead with “significant impact”. And the officers on duty neglected to conduct 30 minute checks of the cell, as per protocol.

The police realised Ms Day’s condition had deteriorated at 8.03 pm and she was taken to hospital in an ambulance. And a scan revealed that she’d suffered a brain haemorrhage. Ms Day never regained consciousness and died on 22 December in St Vincent’s hospital in Melbourne.

In a letter presented to Victorian premier Daniel Andrews on 15 April, her children called for the repeal of the state’s antiquated public drunkenness laws. They point out that while most Victorians have committed this offence, it’s mainly “over-policed” First Nations peoples who are arrested for it.

Systemic Racism

“In a word, it’s disgusting. She couldn’t find her ticket, when she was approached,” Indigenous Social Justice Association member Cheryl Kaulfuss told Sydney Criminal Lawyers. “By all accounts, she wasn’t disturbing the peace.”

The long-term social activist said that, as a non-Indigenous woman, she doubts that she’d be picked up by police under the same circumstances, as this is a law that very much disproportionately affects Aboriginal people.

The laws pertaining to public drunkenness don’t require police to breathalyse a person. It’s at an officer’s discretion to evaluate whether they’re displaying drunkenness. And of course, it’s also up to them to decide who this law is applied to.

“Taking aside that she was taken from the train, the fact that she was left in that cell for four hours without actually physically checking on her deserves questioning,” Ms Kaulfuss continued, adding that if these laws were applied to white people, police cells “would be totally full”.

Long denied

Recommendation 79 of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody states, “in jurisdictions where drunkenness has not been decriminalised, governments should legislate to abolish the offence of public drunkenness”.

Most jurisdictions in the country followed this recommendation after the commission tabled its report in 1991. NSW had already done so in 1979. However, there are two states that have kept these laws on the books: Victoria and Queensland.

“It’s a failure of duty of care, when they know who it’s targeting,” Ms Kaulfuss made clear. “We’ve got the Victorian government talking treaty down here. And meanwhile, we’ve got people being taken into custody. They’ve got no reason to balk at the suggestion that it be revoked now.”

Increasing the punishment

Section 13 of the Summary Offences Act 1966 (VIC) stipulates that “any person found drunk in a public place shall be guilty of an offence”. If arrested over this crime, an individual can be fined $1,289.52 – or 8 penalty units – which seems steep for a crime that many commit.

And while this law might seem like it’s just been hanging around on the books as a leftover from some distant past, a Victorian parliamentary committee’s 2000 Inquiry into Public Drunkenness report details that back then the offence only carried a fine of 1 penalty unit.

This means that Victorian authorities have upped the punishment for this antiquated offence by 700 percent sometime over the last two decades. “Why would you do that if you were just dragging your feet?” Ms Kaulfuss posed. “You wouldn’t be upping the penalty. You’d be looking for an alternative.”

As the inquiry report points out, in common law drunkenness is not simply being seen as drunk, it’s when a person’s “physical or mental faculties or his judgement are appreciably and materially impaired”. But, on the ground, it’s still up to police to decide for themselves what drunkenness is.

Early call for repeal

The Human Rights Law Centre is representing the Day family at the coronial inquest into Aunty Tanya’s death. At the first directives hearing on 6 December 2018, coroner Caitlin English took the unusual step of already stating that she’ll be recommending the law be abolished.

And at the second directives hearing last month, it was put forth that systemic racism should be included in the scope of the inquest, so that the coroner can examine whether it, along racial stereotypes, played a role in the way Ms Day was treated that day.

The humane approach

Recommendation 80 of the Royal Commission sets out that public drunkenness laws should be replaced with the establishment of “non-custodial facilities for the care and treatment of intoxicated persons”.

The next recommendation states that police should be statutorily required to take intoxicated people home or to these facilities. And this is exactly what the Justice for Tanya Day campaign is calling for: that a community health response be put in place to deal with public drunkenness.

Ms Kaulfuss recalled that she was at the recent rally in Fitzroy marking the 28th anniversary of the Royal Commission and a long-term former Victoria police officer told her that back in the day he used to take people he found in a state of drunkenness home.

A nation’s shame

Disappointingly, Aunty Tanya is not the first member of her family to have died in custody. Her uncle Harrison Day died whilst being detained after he was arrested for not paying his fine for public drunkenness.

Mr Day’s death was one of 99 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander deaths in custody the Royal Commission investigated. Indeed, since the time the commission tabled its report, over 400 First Nations peoples have died in custody.

“There’s a total disregard for any respect for our First Nations people”. In fact, “people of colour of any description, as we know with the African kids down here”, Ms Kaulfuss concluded. “Who is going to care? The mainstream media don’t give a toss.”