“Redrawing the Lines of Power”: Peace Activist Jacob Grech on Mounting Global Tensions

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has entered into its second month despite early claims that it would be a fast takeover. And as the Ukrainian civilian population continues to be slaughtered, the Kremlin is now suggesting a potential de-escalation.

But many doubt that Putin’s assertion can be trusted, especially after he repeatedly stated he wasn’t going to commence the invasion of his southern neighbour.

Although his US counterpart Joe Biden did stand on the sidelines, seemingly barracking on the Russian president into moving his troops over the border.

Parallels have been drawn to Russia rolling into Afghanistan in 1979, when the White House was similarly supporting the Mujahideen –those opposing Russia – with weapons.

Back then, Washington was hoping Moscow became bogged down in a prolonged conflict, as it had been during its time in Vietnam.

And further questions are being asked about how the White House might like the current conflict to play out, as many have suggested that Russia’s decision to go to war was long being prompted by NATO’s slow creep across the European continent towards Moscow over the last three decades.

Tensions grow higher

Australian PM Scott Morrison spoke to his Indian counterpart Narendra Modi last week about the war in Ukraine, yet our nation’s leader couldn’t help himself but to continually steer the conversation towards Beijing.

Following on from his September AUKUS announcement, which saw us join a security pact targeting China, Morrison began March by telling the press that his government has decided upon three potential sites to build a military base for housing our coming AUKUS-linked nuclear submarines.

Meanwhile, defence minister Peter Dutton commenced beating the drums of war again last week, when he announced the establishment of the ADF’s new space command unit, which will act to curb Chinese and Russian aspirations on the realms beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

While the recent announcement by the Solomon Islands that it’s negotiating a security alliance with Beijing, sent Canberra into major convulsions, as the government is concerned over suggestions that China could build a military base in the Pacific region.

New lines of division

As these rising tensions have been growing stronger over the last 12 months, a significant change has occurred regarding the role that Australia is now playing in geopolitical issues.

Indeed, our nation has moved to the fore in terms of its positioning in the AUKUS and the Quad alliances.

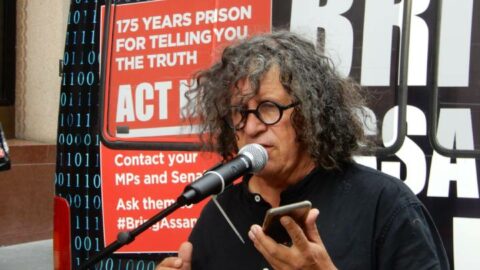

As long-term peace activist and war commentator Jacob Grech tells it, what we are witnessing now is a global realigning of political affiliations, and, as he further points out, in today’s world of the captured state, this also means a realigning of corporate allegiances and access to resources.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Jacob Grech about how his late 2020 assumptions about acquitted NT police officer Zachary Rolfe proved right, the reasons why he considers the conflict in Ukraine to be a proxy war, and questions around what leaders now mean by “the global rules-based order”.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has entered its fifth week. And while Moscow’s takeover was not the quick operation it was supposed to be, the Ukrainian population is being decimated.

Zelenskyy is demanding more help from the west in terms of arms supply. The US and its allies have been willing to provide weapons, yet so far they’ve hesitated on delivering any actual military support.

And Biden was recently in Poland as the war creeps closer towards its border, where the US president made some inflaming remarks about Putin.

So, Jacob, what’s your take on how the Ukrainian war is developing?

It’s a proxy war. Most people outside of the extreme mainstream media would accept this.

In the way it’s developing, it’s not about Ukraine. It has been allowed to develop and to progress so that the project of domination in Europe can continue.

I can’t see it ending in any way other than Ukraine coming down firmly as part of the western alliance.

A lot has been said about NATO provoking Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, in terms of the march the US-led coalition has made towards Russian borders over the last three decades.

Many consider after the end of the Warsaw Pact and the dissolution of the USSR, that NATO should have come to an end. However, instead it slowly incorporated eastern European nations into its fold.

Putin, of course, has been the leader running the preemptive war and making the nuclear threats towards anyone who interferes.

How do you consider the impact of NATO in all this?

To comment on NATO, let’s look at what’s happening in the Solomon Islands at the moment.

They’re talking about a base, and, before you know it, the pro-war brigade on both sides of local politics, and the so-called independent think tanks, like ASPI, are explaining how disastrous it would be.

They’re talking about China having the potential to attack Australia from the Solomons. But China being in the Solomons is more about a different geopolitical strategy to do with the United States being in the Pacific, rather than Australia.

If you look at ASPI executive director Peter Jennings, the main commentator on this, his response is to urge the Australian government to alternatively offer to set up our own naval base on the Solomons.

So, to bring that back to how NATO was involved in Ukraine, that’s just one base in the Pacific that isn’t directly related to Australia. And in keeping that headspace, think of the NATO encirclement of western Russia.

Contrary to the Mutual Obligations Cooperation Act of ‘97, we’ve got nuclear bases in Romania and Poland, equipped with MK 41 missile launchers.

So, just linking the Australian reaction to a potential base in the Solomons, how do you think Russia would be reacting to the encirclement of their western border with missile bases?

I haven’t been to these missile bases, so I can’t say which way the missiles are pointing. But I bet you they’re not pointing back to the United Kingdom, Brexit notwithstanding.

What I’m saying is that while in no way would I excuse the invading of Ukraine, Russia has been pushed to the point that it seems to have said that if it didn’t move now, Ukraine would be a part of NATO and it would place their missiles and NATO – read US – troops within 100 miles of Moscow.

Russia has been inflamed and inflamed.

Also, when we say NATO, we have to talk about the United States, which now seems deeply involved in the coup of 2014.

So, from the start of this whole conflagration, Russia has been pushed by NATO, and aided and abetted by the United States in 2014, to a point where war was the inevitable situation.

PM Scott Morrison spoke with Indian prime minister Narendra Modi last week.

The Australian leader said he understood why India had not moved to condemn Russia’s actions in Ukraine, which is in direct contrast to the way he’s been approaching Beijing on this matter.

Morrison then steered the conversation directly towards Beijing and the so-called rising tensions in the Indo-Pacific.

This is yet another example of how Morrison and defence minister Peter Dutton are presenting Australia as a frontline player in rising geopolitical tensions.

What do you think about this shift that’s occurred during Morrison’s time in office that sees our nation as a frontline advocate for war?

Morrison’s period of government needs to be seen as an extension of Howard’s period, which has all been marked by the culture wars.

Australia has become a big important player, and not just in subservience to the United States. We often see Australia as being in a position where the US says jump and we ask how high.

But rather than serving, which we do on a quotidian level, it’s more to the point where Australia and the US are now serving the same masters of capital. So we’re both interested in the maintenance of the international capitalist system.

What the war in Ukraine is doing, and the rhetoric on China, is not really about Ukraine or the Solomons, what we’re seeing is Australia, America and the United Kingdom, and the Quad to a lesser extent, redrawing political allegiances, which actually means corporate allegiances.

Although India’s position in relation to Russia and Ukraine at the moment is interesting.

So, we’re seeing this redrawing of the lines of power, and like all wars, this one is for the benefit of access to resources. Wars are not about conflict. They’re about accessing resources and trade routes.

So, whether we’re talking about Russia, China or the United States, there are no angels in this. What we are seeing is a proxy war taking place in Ukraine where, as Auden said, “children die in the streets”.

Right now, we’re seeing the redefining the allegiances and the access to resources that are going to determine which centre of capital triumphs over the next quarter of a century. And Australia is involved in that in our region.

March saw Morrison spruiking an east coast base for far-off future nuclear-powered submarines, while, last week, saw Dutton establish a new ADF space unit to protect us against countries, like China and Russia, having their sights focused on the outer limits.

Does our nation really need to be gearing up with these nuclear and space capabilities?

It depends on what you mean by that question. If you mean for the benefit of Australia, the landmass, the people and the biodiversity – everything we think of as Australia – or if by Australia you mean, the financial controls.

The current people who make the controlling decisions and make the profits from them do need those capabilities, so we’re part of the western military-industrial complex. If we don’t have them, measures would be instituted to make sure to bring us back into it.

Obviously, we don’t need these capabilities for the good of the people. But if we’re going to progress down this road of playing a part in western global hegemony, then all of this makes sense.

Submarine bases? We knew there was going to be a new submarine base when AUKUS was first announced because nuclear submarines need a bigger space.

The PM’s announcement of the base in reference to Port Kembla is just Morrison’s electioneering. He’s going to announce the base three or four more times and announce the spending before it’s actually decided on where it’s going to be built.

And the space force? Australia plays an important part in the militarisation of space. When you look at it geographically, in order to download and have communications with satellites around the globe, you need three download stations at minimum.

One of these needs to be in the United States. The other one is in western Europe, and possibly soon in eastern Europe, but the third one necessarily needs to be equidistant from the other two bases and, preferably, in the southern hemisphere.

The western military needs Australia to be onside in the space wars. That’s why Dutton is wanting to separate our space military assets to the air force military assets.

Once upon a time, airplanes were part of the navy, and when they played a bigger role, it was decided they needed their own defence force and became the air force.

So, we’re in that period of technology where we’re seeing the same thing happen with the militarisation of space.

Another point I’d like to make about China in the Solomons is that Beijing had a download station in Kiribati up until 2008. They’re now back in Kiribati, but they haven’t got a download station.

They haven’t got a base station in the Pacific. They’re base station is in China, which is too far away from the west coast of the United States.

So, at the moment, they’re satellite download communications – they’re Pine Gap equivalent – are on an adapted aircraft carrier sailing in international waters in the Pacific.

As well as needing the Solomons as a deep-water port for their submarines and to guard against the US moving into the western Pacific, the other reason that China is so keen on a base in the Solomons is to finally get a permanent satellite download link.

At a forum following the release of the Brereton report in late 2020, you suggested that NT police constable Zachary Rolfe, who shot and killed Warlpiri teen Kumanjayi Walker, was most likely serving in the special forces in Afghanistan.

Since Rolfe was acquitted of the murder of Walker, it’s come to light that while he was over in Afghanistan, he was being mentored by Ben Roberts-Smith.

So, what are your thoughts now that your prediction has been proven correct?

What struck me when the Brereton report first came out and we saw those hideous films in the media, was the state of the camps in Afghanistan.

I’ve never been to a refugee camp in Afghanistan, but I’ve spent a lot of time in Indigenous communities in the desert in Western Australia and the Northern Territory. I’ve spent time in Yuendumu.

So, what struck me when I first saw those images was how similar the Afghan camps look to the Indigenous camps, right down to the camp beds and the posters of Bob Marley.

When we first heard about Zachary Rolfe, we heard about the killing and then him almost being simultaneously charged with murder. And I thought, what are they trying to hide, because an NT copper getting charged for the murder of a blackfella is almost unheard of.

So, I started looking into Zachary Rolfe and I couldn’t find out anything about his service in Afghanistan, except that he was commended for it. But I couldn’t find out which detachment he was in, and this told me he was probably in the SAS.

The things that came out in the Brereton report about the way they shot people, and the way they dropped guns and knives and all the rest of it, just seemed to me to follow this pattern that we saw in Yuendumu. This incident was an extension of what happened over there.

Since that time, I’ve spoken to friends of mine who are former ranking police officers in NSW and Victoria. They both told me that a number of ex-servicepeople are now joining police forces all around the country.

That’s scary because these people are trained in warfare, where they’re in a country and everyone is a potential enemy.

On Zachary Rolfe, after he came back from Afghanistan, his parents became patrons for Soldier On, which is a post-traumatic stress disorder charity for ex-military. And he was also commended for reckless behaviour in saving a woman’s life in the Fink River.

So, a lot of people would have known his history. It’s now come out that he’d had quite a few allegations of going beyond what a normal person would do in his time in the Alice Springs Police Force.

One question we need to ask at the inquest is who made the decision not only to send out their riot squad equivalent to Yuendumu when they knew there was no medical support there.

But another question to ask is in having made that decision why not choose a calm and level headed person who would get the job done right, rather than choose someone who’s known for his risk-taking behaviour and known to be suffering from PTSD.

I hate to say it, but it’s almost like Zachary Rolfe was set up. Everyone knew what he was like, and they sent him out to the community to do something. Even if they didn’t know how he would act, they had a fair chance at guessing how he could react.

And lastly, Jacob, as you’ve mentioned rising global tensions have led to clear lines of division. Australia has joined the AUKUS pact and reinvigorated the Quad, while NATO is realigning in response to the Russian invasion.

And due to these forging of ties in the west, China and Russia have just entered into a “no limits” pact.

Considering that we haven’t seen such a global standoff like this since the 1940s, could we be looking at an escalation into a global war?

I hope not. But we could be. Once Ukraine comes into the central sphere of western influence, Belarus and all the others will follow.

That will realign the power dynamics, every bit as much as the post-World War Two conferences realigned the dynamics then.

The other thing that I want to say about China, and again, I’m not a Sinophile, but it has taken a fairly reasonable position in regard to Ukraine.

Basically, they’re condemning the invasion of Ukraine, but they’re also pointing out that it needs to be settled diplomatically and they’re calling on it to be settled within the United Nations Security Council.

Now, for the past few years, we’ve been hearing the term “the global rules-based order”. Until very recently, it was being used to point to the United Nations Security Council, as everybody recognised this as the global rules-based decision-making body.

But that has now been totally bypassed. It’s been blocked from going to the UN Security Council and instead people are talking about this global rules-based order, which was being used in terms of the Quad.

At the recent conference in Melbourne, every one of the Quad leaders used the term” global rules-based order”. AUKUS used it well.

Everyone is now using that term. So, part of what’s happening here is a redefinition of the global rules-based order towards a form of western hegemony, which sits outside of the UN Security Council, which is a body where both China and Russia, as well as the US, have veto powers.

What we’re seeing here with the alliance between China and Russia is more so a common enemy than friends coming together.

But China is having a reasonable time on this one. It’s just sitting on the sidelines gleefully watching two of its competing centres of capital fighting with each other.

We’ve got no precedent for what has happened here since the Russian invasion of Afghanistan. It had similar precursors with western influences in Afghanistan and Iran in 1979, and look what happened there.

If we’re going to look back in history to any precedent, we should be looking back at Afghanistan.

Back then, the media was speaking about the Afghan resistance fighters in the same glowing terms that they’re now speaking about Ukrainian resistance fighters.

So, it’s only a matter of time.