Refugees Left an Invidious Choice: Barrister Stephen Lawrence on Legal Indefinite Detention

According to Home Affairs, on 31 May this year, there were 112 people amongst the 1,486 individuals being held in our nation’s immigration detention facilities, who’ve been locked away for more than five years.

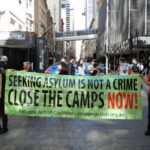

These people are classed as “unlawful noncitizens”, which is a dehumanising term used to refer to refugees, asylum seekers and former residents of this country, who have either never been granted a visa, or have had their visa cancelled on “character grounds”.

These people can’t be sent back to their countries of origin due to our nation’s non-refoulement obligations, under the 1951 Refugee Convention.

Non-refoulement is the principle of not returning refugees and asylum seekers to face potential irreparable harm in the country from which they fled.

So, our government’s solution on what to do with these people – some of whom have never committed a crime, while others have been convicted of minor ones – is to detain them indefinitely, and seemingly in breach of habeas corpus, which implies there must be a purpose in detention.

Sealing the loophole

In a case known as AJL20, the Federal Court ruled last September that a Syrian man who’d had his visa cancelled on character grounds was to be released into the community, because the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) required he be returned to his country of origin “as soon as practicable”.

The 29-year-old refugee had been held in immigration detention for six years. The government hadn’t returned him to Syria because of its non-refoulement obligations. And the court found that his ongoing detention served no purpose, and therefore further detainment was unlawful.

However, last month, the High Court upheld an appeal of this decision. The majority found that the executive branch of government can legally hold a person in indefinite detention when it is an unlawful noncitizen held in administrative detention.

And pre-empting this finding, the federal Coalition in May passed the Clarifying Bill, which closed the legal loophole that emerged out of the Federal Court decision in AJL20.

This legislation effectively clarified in law that the government can hold unlawful noncitizens with no limit.

Indefinite detention or potential death

Together with a suite of other migration laws the Coalition has passed over the last eight years, the Clarifying Bill will see the already sizeable number of people serving what are essentially life sentences without order of the court grow significantly.

NSW barrister Stephen Lawrence has previously discussed the Federal Court AJL20 ruling on the popular legal podcast The Wigs, which he co-hosts. And he took some time out to discuss the implications of the High Court overturning this decision with Sydney Criminal Lawyers.

In September last year, the Federal Court ruled that a 29-year-old Syrian man, known as AJL20, whose visa had been cancelled had to be released into the community.

The complicated argument that led to his release exposed a legal loophole that the government has since patched. Stephen, what are your thoughts on the initial AJL20 ruling?

I was very impressed with the decision of Justice Bromberg. He brought a human rights analysis to the complicated constitutional questions that are posed by the indefinite detention of refugees.

He effectively held that the Commonwealth couldn’t have its cake and eat it too.

The justice found that if the Commonwealth makes a decision not to breach its international obligations by returning a refugee to harm, then the Commonwealth is not able to indefinitely detain the person because the Migration Act – as it applied at the time – provided that a person had to be removed from Australia as soon as practicable.

That, in Justice Bromberg’s analysis, was not happening in circumstances where they could have returned him but chose not to because of international obligations.

So, what Justice Bromberg was doing was calling the Commonwealth on its bluff.

This is a government that has sought to remove visas from people accused of or found to have engaged in wrongdoing at simply extraordinary levels, yet, at the same time, they have sought to not deal with the fundamental question of what we do with refugees whose visas have been cancelled.

What Justice Bromberg did was effectively call out this ongoing and, at that point, unlawful detention of such people.

So, it was a well-reasoned decision. It was a decision that sat comfortably with earlier decisions of the High Court.

And it was a decision that was really in the best traditions of the common law, in the way that the common law values liberty as the most important right in our society.

The High Court, however, has just upheld a government appeal against the decision, affirming that indefinite detention is lawful when its administrative detention involving noncitizens.

What are your thoughts on the High Court decision?

I’m not surprised at the decision of the High Court. I’m not surprised that it was a very close decision, and the case was one that divided the High Court Justices in a fundamental way.

What the majority of the High Court have said is that the Commonwealth is able to indefinitely and, in some ways, unlawfully detain refugees and the only remedy that such a person has is to seek an order that they be returned to the place where they face persecution, harm and in some cases death.

In my view, this is not a decision that embodies the finest traditions of the common law in its respect and valuing of individual liberty.

The implications of the decisions are that unlawful detention is effectively legalised, and refugees are put in the completely unacceptable and invidious position of having to choose between a detention that is not for the purpose of their removal from Australia, or removal from Australia to face persecution and possibly death.

I am not surprised that we saw extremely strongly worded decisions in dissent from the minority of judges.

You provided counsel during a Federal Court case known as MNLR in March. This involved an admission from the immigration legal team that the minister was willing to breach our non-refoulement obligations and return the man involved in this case to face possible irreparable harm in Iraq.

In your understanding, how do we account for the differing positions in AJL20 and MNLR, in that the government wouldn’t send the Syrian man back after six years, but it was willing to send back the Iraqi man?

That’s an interesting question because shortly after MNLR, the parliament passed a government bill that effectively restated our long-standing position that Australia will not return refugees to harm.

This new law has stated that indefinite detention on the count of the owing of protection obligations is now lawful.

So, what was said with MNLR appears to be an aberration and the correctness of the statement in court from counsel for the minister is far from clear.

So, the Clarifying Bill has ruled out the suggested willingness of the minister to send MNLR back to Iraq?

Yes. The Clarifying Bill provides now that the person is to be indefinitely detained if they are a refugee. And that it’s not lawful to remove them unless certain circumstances are met, for example, that they consent to removal.

So, the new law is effectively enacting in law this invidious and quite scandalous state of affairs that flow from the High Court’s decision in AJL20, which puts on refugees to make a choice: either stay in Australian detention for the rest of my life or be returned potentially to my death.

That choice is not a choice that any civilised country should be imposing on some of the world’s most vulnerable people.

The argument that saw the Federal Court release the Syrian man in AJL20 was based in part on the principle of habeas corpus, which implies there must be a purpose for detention to make it lawful.

In your opinion, does the recent High Court ruling undermine habeas corpus?

The decision of the High Court in AJL20 poses profound and very concerning long-term implications for the role of habeas corpus in our legal system.

It has always been the case that there will be a remedy for unlawful detention and that remedy will be an order for release.

It’s difficult to see how the majority of the High Court has not moved away from that position. The implications of that, in my view, will take some time to become clear.

And lastly, Stephen, AJL20 seemed to indicate that there was an issue with the over 100 unlawful noncitizens the government has in immigration detention who’ve been there for more than five years now.

However, the High Court has said this is wrong. And the Morrison government amended the Migration Act in May to ensure the loophole that was exposed has now been closed.

What are your thoughts on Australia maintaining a system of long-term and indefinite detention specifically for people classed as noncitizens, who aren’t being held in relation to being punished for any crime?

It’s a scandalous state of affairs. It’s important to remember that people can be placed in that situation without ever being charged with a criminal offence, while many in this situation have been convicted and sentenced for criminal offences that are not of the highest level of seriousness.

Australia has developed a system of visa cancellation that’s draconian. It is interfering in our international relationships. It is wreaking havoc in immigrant communities across the country.

It sets us apart from the way that other developed countries deal with these issues.

It’s simply become an obsession – a fetish – and these policies are being implemented without proper regard for their impact on human beings.