Release Immigration Detainees for COVID: An Interview With Advocate Margaret Sinclair

Photos displaying the cramped living conditions that immigration detainees are continuing to be held in at Avon Compound within the Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation (MITA) detention facility are currently being shared amongst refugee advocates online.

The images reveal rooms packed with bunks beds. And with the onset of COVID-19 and the lack of any provisions being made to ensure detainees can practise social distancing, or even the absence of any adequate coronavirus information, mean these rooms could easily become virus incubators.

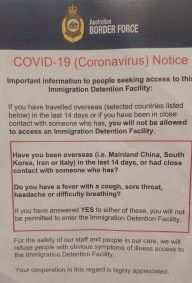

There’s only one COVID-19 notice displayed at MITA. And it deals with restrictions on visitors coming from overseas. There aren’t any notices about how to take proper measures to prevent catching the deadly virus. Indeed, there aren’t even any warnings in the large shared bathrooms.

Right now, around 1,400 detainees are being held in onshore immigration detention and transit facilities. And, because all centres are controlled by Australian Border Force, it can be assumed that the absence of any measures being taken at MITA are being mirrored at all these centres.

Expert medical advice

The Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases and the Australian College of Infection Prevention and Control released a joint statement on 19 March. It notes that the PM has recommended social distancing and isolation practices, which asylum seeker and noncitizen detainees can’t maintain.

And, based on the evidence of what happens when coronavirus outbreaks have occurred in other crowded settings, this would potentially pose a risk if the virus does enter into one of these closed environments.

The joint statement further asserts that if there is an outbreak in immigration detention then staff are at risk of both catching COVID and passing it onto others in the wider Australian community. And for these reasons, it calls for the immediate release of detainees that pose no risk.

NSW parliament passed emergency laws on 24 March that allow for the release of certain inmates who are close to finishing their sentences. While the UK government has just released around 300 immigration detainees in relation to the pandemic.

Work health and safety

Margaret Sinclair is a work health and safety expert. And as detention facilities are places of work, federal workplace safety laws apply. Recently, she’s been liaising with Comcare in regard to health and safety issues being posed in immigration detention on behalf of Doctors 4 Refugees.

The long-term refugee and asylum seeker advocate points to a recently published paper in The Lancet outlining that “prison health is public health by definition”. And she makes certain that this equation can easily be applied to Australian immigration detention centres.

The paper researchers go on to recommend that because of the “very porous borders” between detention facilities and the outside, during COVID it’s “crucial that prisons, youth detention centres, and immigration detention centres are embedded within the broader public health response”.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Ms Sinclair about the distinct risk that those in immigration detention now face, the lack of any adequate provisions being made to prevent an outbreak inside, and how release into the community makes both health and financial sense.

Firstly, Ms Sinclair what are the issues being faced in immigration detention facilities as the coronavirus starts to spread in this country? And what are the health risks involved?

The main issues are that being confined means there’s no chance for social distancing or for the detention network as a whole to provide self-isolation for the number of people who may end up needing it.

It’s not possible to have social distancing in a shared dining room or shared bedrooms or when security is physically doing room searches or pat downs or even in escorting some of these people to medical appointments.

There have been stringent measures put in place which restrict visitors and banned visitor contact, but as of 24 March, all visits, whether personal or not, have been be banned.

Staff working shifts – whether we’re looking at security, cooks, cleaners or medical professionals – are in regular contact with both the outside world and the people who are detained. So, they pose the greatest health risk.

They would be the only ones to carry the virus into these centres, and to carry it out again.

Let’s say that among the general population approximately 30 percent of people contract the virus, if it were to get into the detention centres, there’s a high probability that the percentages could be in the range of 60 to 70 percent.

These places are like petri dishes for viruses. We have seen this already with rates of malaria, dysentery, typhoid, gastroenteritis, dengue fever, influenza and H-pylori in closed detention centres on both Manus and Nauru simply because of the overcrowded living arrangements.

Coronavirus is also more dangerous if it gets into detention centres because then there would be a high likelihood of it being carried out of detention into the wider community by staff.

Coronavirus in detention is not just an issue for refugees, it’s also a public health issue.

The federal government has been quite consistent in its announcements of responses to COVID. What has it – or the immigration department itself – done regarding those in detention?

As far as I have been able to ascertain, there has only been signage and advice regarding visitors.

There’s no signage in the compounds, including the shared bathroom facilities, whether in English or translated into other languages.

There have been some meetings with detainees, such as the ones in Brisbane, where Serco announced that one of the guards had tested positive for COVID-19.

I am aware that people who arrive on planes and who once spent a very short time in detention before being deported are now not going into traditional detention, but into the motels being used as alternative places of detention (APODs).

Otherwise the government has been not so curiously silent on the matter.

At a guess, it’s likely that the Australian government wants to believe it can conduct “business as usual” and believes that it can manage risks. It hasn’t worked in the wider community and it won’t work in detention centres either.

As mentioned, medical experts, along with refugee and asylum seeker advocates, like yourself, have been calling for adequate responses to protect the health of these detainees. What should be happening in the case of these people?

The first action in a pandemic situation is that the government should be listening to medical experts. This shouldn’t even be up for debate.

In fact, when it comes to places of immigration detention, the government is obliged to be compliant with the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (Cth) (WHS Act).

In particular, there’s the primary duty of care in section 19. It requires Home Affairs-ABF to pro-actively and preventatively ensure that the health – including psychological health – and safety of detainees and workers is not put at risk by a detention centre’s design or operations.

Then there’s section 27, under which “officers” – top decision-makers – have a duty to “exercise due diligence to ensure that Home Affairs-ABF complies with that duty and all other such duties. Failure to comply with a health and safety duty is a heavily penalised criminal offence.

In order to comply with the section 19 duty, Home Affairs-ABF must go through the hazard ID and risk elimination process of sections 17 and 18.

In brief, that means identifying all hazards, risk assess each one, thereby teasing out the serious risk, then eliminate all such risks or if total elimination is not practicable, at least minimise and control them.

The fact is that, in the detention centre setting, the serious risks are already well known, and Home Affairs-ABF must, as a matter of law, listen to the medical experts who, in relation to COVID-19, tell us how to eliminate or at least minimise that risk.

In my opinion, it’s not enough for the risk assessment to be general. It’s not one size fits all. The risk assessments should be individual, since every person has a different level of risk if they were to contract the virus.

For instance, 2-year-old Isabella at MITA has higher risks than an adult. But older adults, such as those over 50, would have different risk ratings altogether.

Those who are smokers are at a higher risk than those who are not. Those formerly on Nauru who had already been exposed to toxic mould from the tents or dust from the phosphate mine or had been diagnosed with latent tuberculosis are at a very high risk.

Anyone with an immune compromised system would have an extremely high risk rating if they contracted COVID-19.

Though, as for that, stress is known to suppress the immune system, so in that sense everyone in held immigration detention would have a reduced ability to fight infection.

Even if all this was done, have the residual risks and hazards also been identified and addressed? Risks to the mental health from banning visitors or use of the gym? Risk to mental health from being locked up 24 hours a day in the motel accommodation known as APODs.

And the risk to the mental health of people who have already experienced previous serious – and potentially fatal – illnesses on Manus and Nauru.

In this current COVID-19 pandemic, it’s obvious to me that the current responses from the government have been inadequate.

They haven’t addressed the main hazard which comes from staff inadvertently bringing in the virus, they can’t ensure social distancing or isolation, and it’s likely that individual risk assessments have not been undertaken.

Even the basics such as signage in the bathrooms relating to washing hands has not been done. This is something that should be brought to the attention of Comcare, the regulator of the WHS Act.

The bare minimum should be single bedrooms, separate bathroom facilities and spaced out dining times. The bare minimum isn’t happening and isn’t enough to prevent the contraction of this virus.

What should be happening is the same as what has happened in the UK and the US recently.

Prisoners have been released from gaols in the US and people who are detained in UK immigration detention have also been released.

A large number of people can and should be released from Australia’s immigration detention centres and APODs. This should happen proactively and preventatively, before the first people detained catch the virus and spread it.

If the Australian government has received high level advice in relation to releasing people from detention, then they should act on that. If they have not, then we should be asking, why not?

Mr Outram, the commissioner of Australian Border Force, and Dr Gogna, the chief medical officer within ABF, both have officer duties under section 27 of the WHS Act.

They should have advised Mr Pezzullo and minister Dutton of both the risks and residual risks and the means to eliminate them.

As you’ve mentioned, there are also the offshore asylum-seeking detainees who were brought across to Australia to receive treatment under Medevac, and have since been stuck in motels, referred to as APODs, with restricted movement.

These are people who have been in long-term detention and have ailing health. What sort of issues are there around the conditions they’re being held in as the threat of the coronavirus mounts?

There would be well over 200 in there by now. People who were approved under Medevac were still brought here after that law was repealed.

There are also others previously held on Manus and Nauru, who also arrived in Australia for medical treatment though not under the Medevac law. They are both in APODs and immigration detention centres.

The issues are many. These people are already on long waiting lists for medical treatment, where the wait times are likely to blow out further due to medical facilities dealing with COVID-19.

Protracted and indefinite detention has already negatively impacted their mental health, and having extra fears of contracting this virus, when so many protective factors are out of their control, makes this worse.

It’s impossible to have social distancing between guards and the people detained, as well as between people detained especially when the top bunk is less than two metres above the bottom bunk.

Overcrowding and lack of self-agency to manage one’s own health are the main conditions that make this pandemic such a threat to the health and lives of those in detention.

Indefinite detention, in and of itself, is the issue and it’s impossible to mitigate this. The Australian government needs to let go of its fear mongering and set people free. It’s the only thing that will result in saving lives.

Then there are over 400 people still being held in immigration facilities, transit centres and in motels on Nauru and in Papua New Guinea. What’s happening with them?

For the past two months or more, there have been no medical transfers from Nauru to Taiwan for medical treatment. And now that Nauru has put itself in lockdown, this would also affect any potential medical transfers to Australia as well.

Both Nauru and PNG have limited capacity to deal with a pandemic such as COVID-19. PNG has just announced a two week lockdown but there’s already at least one case of identified COVID-19 in that country.

The refugees housed in hotels have very limited means to be able to afford 14 days’ worth of the basics to be able to ensure hygiene and a healthy diet should services close, this, in turn, would put their health at further risk.

On top of this, it seems that third country resettlement has been put on hold by the UNHCR. And although a number of people had been approved for the US, they may not be able to travel there under the current pandemic situation.

I am genuinely concerned for the refugees in both countries. They have been there for far too long and now it’s just more complicated trying to end the situation so that they can finally have safe resettlement.

Most of the people in immigration detention haven’t committed any crimes. Even the 150-odd New Zealanders the government is currently detaining and deporting – mostly over minor offences – have already served their time.

So, aren’t there some duty of care issues around the government containing these sorts of people during a pandemic?

There are duty of care issues around the government containing these people even without a pandemic. In my mind, detention of this nature serves no purpose at all.

The duty of care issues are most easily seen through the lens of the WHS Act. If due diligence is not being complied with, if medical advice is being ignored, if individual risk assessments have not been performed, then it’s possible that the Australian government is committing a category 1 if not a category 2 offence.

The WHS Act is criminal law and these possible offences are criminal offences.

The government appears to be reactionary, rather than proactive. The duty of care extends beyond the risk of contracting the coronavirus, it also includes the psychological health of people detained who will now not have access to fresh air and sunshine if they are held at Kangaroo Point in Brisbane or the Mantra Hotel in Melbourne.

They will not be able to have social support and a lift to their mental health through personal visits.

Nothing done so far has ameliorated the living conditions of having more than one person to a room or several people sharing the same bathroom or dining space in any detention centre.

And lastly, Ms Sinclair, is it feasible that the government could release at least some of these people into the community so they could keep up social distancing requirements and self-isolate if necessary? Could our system afford to do that?

Yes, it’s feasible. The UK and the US have already acted to release people from immigration detention and prison facilities.

They recognise that it’s the appropriate and reasonable response to make. Medical experts in Australia have also urged the government to release detainees.

All those with family in the community who have offered to accommodate relatives could be released very quickly because they already have somewhere to go.

Most people within the group of detainees whose visas have been cancelled under the Migration Act’s section 501 “character test” provisions have homes in Australia.

There’s also housing available for the government to use for community detention which is currently empty or only partially used.

In fact, social distancing and self-isolating would be more successful once a person is released because community detention would ensure people have their own bedroom and fewer people sharing the bathroom and kitchen facilities.

Everyone who arrived under Medevac already have security clearance. Many of them have supporters in the community happy to assist them and have written letters detailing this support to the relevant detention centre case managers.

Some of these letters also offer accommodation which has already been assessed by ABF-Immigration.

Releasing anyone who’s a high risk of adverse health outcomes due to age or other health issues is a must. I fail to see how a government can refuse to do that and still comply with the WHS Act.

There’s no excuse for not acting quickly in these cases to release these people. Following what the UK and the US have done is a sensible and practical response to the coronavirus pandemic.

Since community detention is so much cheaper than held detention and the likelihood of better health outcomes are also much higher, our system could most definitely afford to release refugees and others held in detention into the community.

What we can’t afford is to have a government so paralysed by their own ideology and hard headedness that they continue to put people’s lives at risk, both those detained and the wider community.

The current situation in detention dealing with the COVID19 pandemic is untenable. The government would be a fool not to release the majority of these people.