Social Housing Building in Hard Lockdown: An Interview With Common Ground Resident Action Group

At 8am on 2 September 2021, residents living at Camperdown’s Common Ground social housing estate woke to find themselves in hard lockdown. So, from that moment on, they were no longer permitted to leave their units due to COVID-19 concerns. And this applies for 14 days.

Two residents in the building tested positive to COVID-19 on 29 August, and two more were found to be positive on 1 September. Yet despite this, the residents weren’t given any prior warning that a hard lockdown was to be implemented, so they had no time to prepare.

As for the four COVID positive residents, they’ve been removed to a health facility elsewhere, as have ten other residents that had been confirmed as close contacts. The building has undergone a deep cleaning, and door-to-door COVID testing has taken place.

However, residents of inner west Sydney’s Common Ground are upset about the way this extreme confinement was dropped on them without any prior notice, especially as there was a period between the first cases being detected, and the decision to instigate the hard lockdown.

Housing first

Common Ground was purpose-built to accommodate people who had been experiencing homelessness. Run by Mission Australia Housing (MAH), the Common Ground project is based on the Housing First model, which provides accommodation, along with wraparound support services.

As the Common Ground Action Group explains, “the estate holds 130 residents and is home to many people who were formerly homeless, including members of the Aboriginal, transgender, migrant, and refugee communities”.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Common Ground Resident Action Group spokesperson Robin E, who’s currently in hard lockdown. Robin filled us in on how residents are feeling, about the lack of adequate communication, and the list of demands they’ve put to the authorities.

On 2 September, residents at Common Ground were placed in hard lockdown, which means you’re confined to your unit and can’t leave until 15 September.

You weren’t given any notice despite COVID cases having been detected in the building for a number of days prior. Robin, can you describe how you came to find yourself in hard lockdown?

I had an inclining that it was going to happen. I knew that two cases had been found. And a few days later, I thought that they were going to try and lock us in.

I was up early. I wanted to leave because I wasn’t sure if I could handle two weeks in lockdown. But I stayed because this is my home, and I don’t really have anywhere else to go.

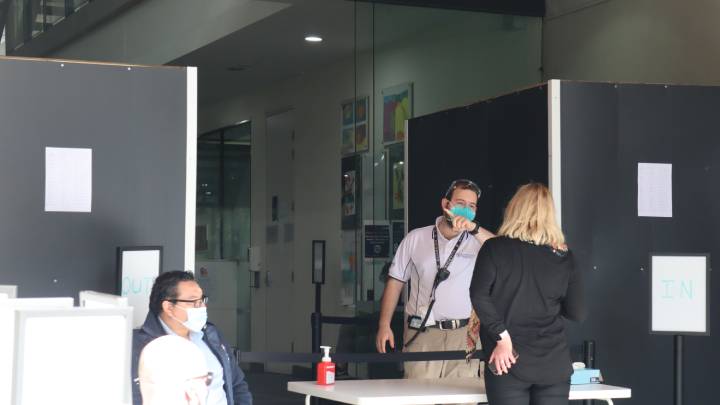

At 8am, I looked out the window and the place was surrounded by police and people in PPE. They were also on every floor. They told us the place was in lockdown.

We didn’t get the message from Mission Australia Housing.

There were police and security on every floor. That is how we found out. We just walked out and were told we couldn’t leave.

So, how did that make you feel?

Trapped. I felt like I’d done something wrong.

How would you describe the way in which the locking down of the building was handled? Could the approach have been better?

Absolutely, it could have been better. They could have let us know earlier.

The idea is that if you know you’re going to be in lockdown, you would make a run for it. So, I guess they’re trying to contain the spread of COVID-19.

But, mind you, there are many buildings in Sydney with strata management that also have had cases like ours and they aren’t in lockdown. So, it’s because we live in social housing and we’re a vulnerable group.

We have people living with addictions. They have a challenging time in their own life. And this is an opportunity for police to stop and search everybody out the front of our building, to find out who is using drugs and what our relationships are like.

The invasion of privacy and the lack of advocacy for people, they count on that. They count on us being a disparate group. That’s part of it.

We are being treated differently from people who live in private accommodation in a strata apartment, for example. They’re not being paid attention to in the way that we are.

This is a class issue. It’s about discrimination. It is about us being poor and not having the resources to fight back.

You’ve just touched on my next question, but who lives at Common Ground? And why is the approach there different to elsewhere?

We had a meeting with MAH last night. MAH said they were not responsible for the surrendering of the building to NSW Health, which I find hard to believe.

The people who live here are on low income. They are young people. They are people recovering from drug and alcohol addictions. They are people seeking shelter from domestic violence. There are cancer patients.

These are people who are trying to find affordable accommodation in Sydney.

The Common Ground project itself is quite amazing. It is something. I have seen people recover. I have seen people leave. I have seen people change their lives in here. It is an amazing place.

It’s a tight knit community, as disparate as people might think it is. It is a beautiful community.

The problem with the way MAH has handled the situation is that they did not notify us at all.

We rely on their services day-to-day. And they didn’t communicate with us that they were going to leave the building. They didn’t tell us that NSW Health was taking over.

Then NSW Health didn’t communicate with us and tell us how they were going to carry out their plan, including how we would be able to get food or communicate with others.

It is absolute chaos in here. People are frightened. They are locked in their houses. I have friends in the building that are elderly. I have relationships with people, and I can’t talk to them. It is like they are keeping us separate.

So, residents received no time to prepare for 14 days without being able to leave their units. Has this created issues with supplies? Are your needs being seen to?

In the first two days, they delivered a box of food from the food bank. They delivered a couple of meals in the evening. But people have dietary needs. Not everyone eats meat. Not everyone can eat wheat. They didn’t check.

They didn’t ask what people needed. It was simply being locked down. It takes 15 hours to get a delivery from Woolworths. Their online ordering system is obviously clogged at the moment.

People are frustrated and angry. They couldn’t get what they needed.

The other thing is the blocking of supplies for people with opiate addictions or other drugs. So, they have to handle it. There is a lot of shaming around drug use. But it’s just a fact.

We’re also not able to get our orders in. They’ve been searching our bags. They have been taking away things like liquor, hard spirits. They’re telling us what we can drink and how much we can drink.

They haven’t told us why that’s how much we can drink. It is just a health order. And nowhere is there a copy of this health order.

We don’t have any ability to see this health order and where the law says when you are in quarantine how much you are allowed to drink.

We don’t know why the police are suddenly searching the bags of people coming in.

The elderly mother of a young woman who lives in our building came to deliver a package. It was a microphone and a little speaker. And the police dismantled it because they thought she was smuggling in drugs.

What is that about? Is that standard across the city? Is that what they are doing at every complex? No. It is just us.

So, there’s a specific health order for your building but you have no idea what that entails?

Basically, there has been little to no communication with the authorities. We don’t have a liaison with the police. We don’t know who is working in the building. They don’t have identification.

They tell us they are from NSW Health. But why should we trust them? MAH have abandoned everything on the ground. And they are the ones that we have relationships with.

We don’t know the law. And we don’t know our rights in here, yet. But we are working on it.

Robin, you and the other residents have formed the Common Ground Resident Action Group. What are you calling for? And what would you like to see put in place for the rest of your confinement?

We have a list of demands. First and foremost, we want communication with our neighbours, and we want to organise a town hall Zoom meeting with all the residents.

We want residents without phones to have access to one to be able to communicate.

We want fresh fruit and vegetables. We want fresh produce: bread, milk and meat.

We want people to have access to dog walking services, because a lot of people in here have dogs.

We want a rent-free period of lockdown, because we don’t want to be charged for rent, while our homes are being used as lockdown facilities. They’re being used as medical cells.

We want emergency payments for everyone in Common Ground. And we don’t want to be hassled about how to get that money to be able to live.

A lot of people have jobs in here. They may be low-income jobs, but they are jobs, nonetheless. And these people have lost these jobs because of the lockdown. So, we are looking for compensation.

We want respectful and culturally appropriate healthcare rollouts. So, testing and vaccinations must be carried out in a kind and courteous manner. We want people who don’t speak English to have translators.

There have been a lot of complaints about the testing. There have been reports that they’ve been aggressive. Some people say they feel assaulted. We’re working to make sure that doesn’t happen.

We are also concerned about the airborne quality of COVID-19, as we’re concerned about whether it can travel through the ventilation in the building.

We are trying to see whether people who have tested negative twice can leave the building before the 14 day period is over.

We also want to know where our neighbours are being taken. So, if somebody is being taken away in the middle of the night to a different facility, we would like to know where they are going.

So, people have been removed but you haven’t been made aware of what is going on?

Yes. People are being removed in the middle of the night by the state. They are not telling anybody where they are going because, apparently, it’s a privacy issue.

And we just want the police to stop searching our bags, please.