Still No Justice for David Dungay: Family Rallies at Long Bay Eight Years On

Today marks eight years since David Dungay Junior, a 26-year-old Dunghutti man, was set upon by a group specialist guards in the hospital ward of Sydney’s Long Bay Gaol, who aggressively forced him down face first onto a prison bed and secured him in the prone position until he ceased breathing.

On watching the footage, it is quite unbelievable that the violent pursuit of the First Nations inmate was triggered by the fact that Dungay, a diabetic, was eating a packet of biscuits alone in a cell that was locked, and he was refusing the advice of a nurse to stop consuming them.

And it is not as if the highly trained officers that were called upon to secure Dungay were completely ignorant to the risks. The prone position is notorious for causing fatalities. And the young man himself called out that he couldn’t breathe to those upon him, at least a dozen times.

Yet, whilst Dungay’s death was completely avoidable, the fact that an Aboriginal inmate died at the hands of guards, the fact that a subsequent inquest into his death resulted in no charges being laud and the fact that eight years on justice has still not been served, are no anomalies.

The Dungay family has not given up on its fight for justice for David, however. And the Dungays and their supporters are gathering out the front of Long Bay Correctional Facility this Friday, the 29th of December, exactly eight years after David’s death.

“I can’t breathe”

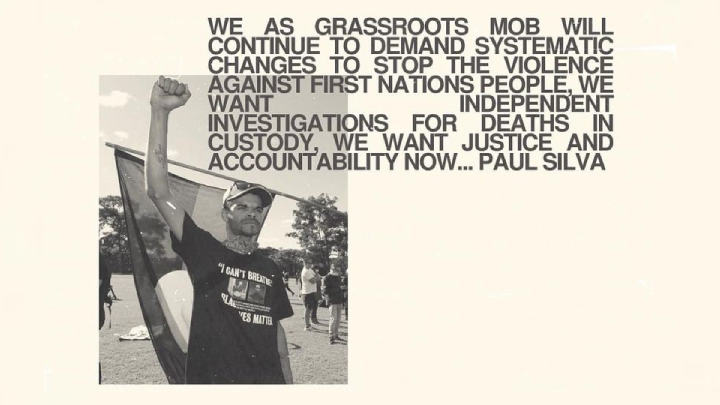

“It’s important to remember the life of David Dungay Junior and also to recall the corrupt system that we live under and that we have to deal with on a regular basis in regard to these incidents,” Paul Silva, David’s nephew, told Sydney Criminal Lawyers.

“It’s been eight years for my uncle, but it’s been many more for others. This is a prime example of how the system works,” the Dunghutti man continued. “There is no form of accountability or justice for the family or the individual who perished at the hands of police, corrections or Justice Health”.

In fact, since David’s death, the Dungays have kept up their demands for justice via a range of rallies and public appeals. And Silva was at the heart of the massive Black Lives Matter demonstrations that rocked the Sydney CBD and other parts of the state in mid-2020.

The BLM rallies were sparked by uprisings in the US, following the police killing of George Floyd. The similarities between the Black man’s death in the US, which saw him repeatedly call out, “I can’t breathe” as Minneapolis police held him in the prone position and that of David, was lost on no one.

“Eight years is too long for justice for David and me. I have had to come to terms with maybe never getting it. But I am still determined to,” Silva made clear. “That’s not going to happen unless Albanese starts to listen to the families and implement policies around deaths in custody.”

A nation’s shame

In regard to the Dungay case, and, as Silva highlights, in the overwhelming majority of other Aboriginal deaths in custody cases, no disciplinary action was taken against the assailants.

Indeed, Black deaths in custody that result in charges being laid cause a stir because they’re so rare.

And two recent deaths diverged from the regular scot-free path. NT police officer Zachary Rolfe was charged with the 2019 murder of Warlpiri teenager Kumanjayi Walker, whilst a Corrective Services NSW officer was charged with the murder of Wiradjuri man Dwayne Johnstone in 2021.

Yet, despite both these killings finally resulting in actual criminal charges, both these men were acquitted of the crimes.

As Aboriginal deaths in custody had long been an issue, the Hawke government convened the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody in 1987, and it handed down its final report, including its 339 mostly unactioned recommendations, in 1991.

The Australian Institute of Criminology Aboriginal Deaths in Custody count outlines that since the Royal Commission, 557 First Nations people have died in the custody of corrections or law enforcement. And just over the year 2023, 20 Indigenous people have lost their lives in custody.

“There has been a high rate of deaths in custody since 2020. Over the past three years, the statistics have risen,” Silva explained and added that another “death in custody happened on Christmas day”, as a 46-year-old First Nations man was found unresponsive in his cell in Perth’s Casuarina Prison.

“I send out my condolences to the family at this traumatic time; being a family member who went through this, I know exactly how they are feeling at this moment,” he continued.

One of the reasons behind ongoing Aboriginal deaths in custody is the disproportionate numbers of First Nations persons being incarcerated in Australian prisons, as they currently make up 33 percent of the adult prisoner population, whilst they only account for 3 percent of the entire populace.

Marking eight years

The last third of 2023 has been marked by events that serve to highlight the ongoing injustices that First Nations people suffer under the imposed European system, after over 230 years of the settler colonial project having commenced on this continent.

The nation voted no at the referendum for a powerless Indigenous voice or nonbinding advisory body to parliament in early October. And this was due to a scare campaign propagating the myth that this body would be all too powerful and translate into divisions within the community.

And just as the news of the referendum’s negative result came in, the Israeli government’s genocidal operation on the occupied Palestinian population of Gaza commenced, which, especially as the Albanese government supported Netanyahu’s assault, reopened old and ongoing wounds over here.

Over 20,000 Indigenous Palestinians have been killed at the hands of the settler colonial Israeli state since 7 October.

“Indigenous people relate to what’s occurring in Gaza, which has been ongoing for quite some time now,” Silva emphasised. “We are fighting this not just inside of Australia but outside of Australia as well. It is a constant battle being an Indigenous person.”

“This shows that these systems are set up to dispossess Indigenous people in their homelands, whether that’s in Australia or outside of it.”

David’s mother, Leetona Dungay, has organised the Eighth Anniversary Justice for David Dungay Junior rally that’s meeting out the front of the Long Bay Correctional Complex at midday on 29 December.

“We haven’t had a rally for quite some time now,” Silva continued. “So, it is very important that Corrective Services know that we are still here, and we are still fighting for him. We are going back out there to make them aware that David’s life still matters, even though it is eight years on.”

The social justice activist added that the family wants those visiting inmates on Friday to know that the facility is something of a “murder haven when it comes to abuse of authority and excessive force”.

“The statistics speak for themselves,” Silva said in conclusion. “There has been a large rate of Aboriginal deaths in custody since 2020. These things still occur. There is no justice or accountability. And families continue to sit through coronial inquiries, when they should be sitting in the courts.