Stop COVID Aboriginal Deaths in Custody: An Interview With the ALS’s Makayla Reynolds

Right now, as COVID-19 cases continue to climb, people are being told not to leave their homes unless it’s a necessity. And authorities nationwide are enforcing these new regulations, ensuring compliance via threat of steep penalties.

Yet, despite the potential impact a coronavirus outbreak in a correctional facility could have – as well as rising calls to release nonviolent prisoners into the community – not a great deal has been done so far to reduce the numbers being held in this nation’s overcrowded prison system.

And the sad truth is that concerns being raised about the virus spreading throughout correctional facilities first and foremost relate to the First Nations population, as proportionately they’re the most incarcerated people on the planet.

According to ABS figures, last December there were 42,799 adults being detained in this country’s gaols. And of them, 11,776 were Indigenous. So, while First Nations people make up less than 3 percent of the general populace, they account for 29 percent of all adults in the prison system.

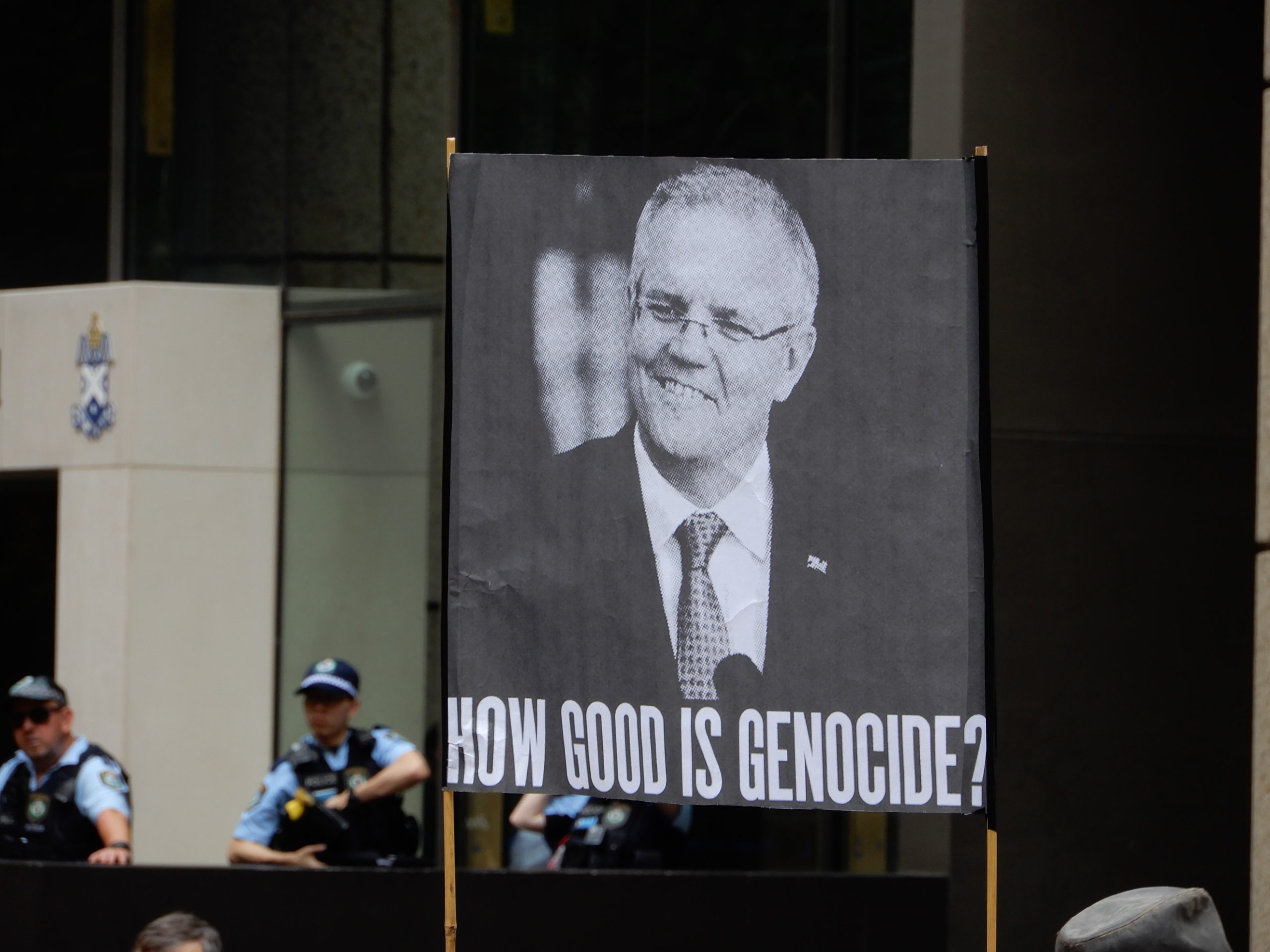

Further genocide

One thing that’s clear about the novel coronavirus is that it’s more likely to take the lives of the elderly or those with pre-existing health conditions. And another sad indictment of our nation is that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have poorer health outcomes than the non-Indigenous.

This is the legacy of over 230 years of dispossession and colonisation. First Nations people were robbed of their lands, their resources and their ways of being. And after being pushed to the peripheries of settler colonial society, they were then blamed for their reduced circumstances.

Aboriginal deaths in custody have long been an issue in this country. So much so, that a Royal Commission into the matter was held. However, since it handed down its 339 recommendations in 1991, there have been more than 400 deaths of this nature.

And now, with the burgeoning COVID pandemic, Australian authorities are yet again in a position to do something decisive – and morally correct – which would prevent numerous Aboriginal deaths taking place in correctional facilities owned and funded by the colonial state.

Preventable deaths

The Aboriginal Legal Service NSW/ACT (ALS) has just launched the Stop COVID Aboriginal Deaths in Custody campaign, calling on Australian governments to follow the lead of other countries and release vulnerable inmates into home detention.

ALS staff member Makayla Reynolds is heading the campaign. The Gamilaraay woman knows all too well how Aboriginal people can be neglected on the inside. In September 2018, her brother Nathan died tragically in a state facility, due to an asthma attack that prison authorities failed to respond to.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Ms Reynolds about the measures being taken overseas to prevent the spread of COVID in prisons, the NSW government’s new laws permitting the early release of certain prisoners and her concerns that First Nations people will be targeted by new pandemic laws.

Firstly, it’s been widely acknowledged that the overcrowded NSW prison system won’t be able to cope if a COVID-19 outbreak occurs in one of its facilities.

The Aboriginal Legal Service NSW/ACT is running a stop COVID Aboriginal deaths in custody campaign. Makayla, what does this involve? And why is it necessary?

Last week, we put out a call to governments, asking them to ensure the release of some of the many thousands of First Nations brothers and sisters locked inside overcrowded prisons. An outbreak in prison will be fatal.

We are also worried for our elders. It wasn’t that long ago when our old people were afforded no rights on the missions, and no access to healthcare.

Our lands, languages, families and cultures have remained under attack to this day. Our mob are already suffering and chronically ill from this historic and ongoing injury.

We fear the bodies of our people won’t be able to handle this disease, as seen with thousands globally already killed by this pandemic.

Already, 5,000 people have stood with us in calling on governments to act, since launching our campaign just days ago.

The ALS is running an online petition calling for the temporary release of inmates with high health needs and most at risk of getting the virus.

Would you say there are a lot of Aboriginal prisoners currently at a heightened risk if an outbreak occurs?

Yes. In 2018, my brother Nathan died from an asthma attack in prison. It took 40 minutes from the first call for medical help to arrive, despite the pleas and screams of the young men around him. But it was too late for my brother.

COVID-19 is a pandemic that will impact everyone. But, most at risk are people like my brother: Aboriginal, chronically ill and incarcerated.

My brother, a proud Aboriginal man and loving dad, had a known asthma condition and couldn’t survive the conditions of a minimum-security prison.

How on earth will our people held in prisons survive a pandemic? They wouldn’t.

The NSW government passed emergency laws last Tuesday, which include provisions that allow NSW Corrective Services commissioner Peter Severin to grant early parole to certain inmates.

What do you think about this move? And considering it doesn’t address those on remand, is it enough?

Anything that helps to get our mob out of custody and to a safe environment during the pandemic is a good thing.

But it’s not enough. We need freedom for First Nations people on remand, and those nearing the end of their sentences.

We need them home with their families or supported in safe accommodation. And priority testing for prison workers and all people held in prison.

The sick, the old, the kids, many who have acute health conditions like my brother, mothers and their babies, are in grave danger.

Just this week, we learnt that an employee in a NSW prison hospital has tested positive for COVID. So, when the virus spreads to prisoners, the results will be catastrophic.

All governments should be acting today to prevent countless more Aboriginal deaths in custody before it’s too late.

In your understanding, what’s happening elsewhere in the world regarding prisoners being stuck inside or released during the COVID crisis?

Overseas we’ve seen lots of other countries acting fast to release people in their tens of thousands.

Iran has released 85,000 people. Ireland will release people with less than 12 months to serve. The United Kingdom, and some states in the USA, have followed.

But we’re also seeing the disastrous consequences when governments don’t act fast enough.

So far, in New York City, there’s been 167 people in prison and 114 Department of Correction staff members who have tested positive for COVID-19: the disease caused by the coronavirus.

And in your mind, what does it mean if the settler colonial state continues to incarcerate First Nations people during a pandemic like this?

Since British arrival, police and countless other government agencies have targeted our mob.We know this because of the raw numbers recorded and the countless inquiries.

We also know this because this is our everyday lived reality. If you’re black, police are a fixture in daily life – even if we’re just walking down the street to get milk.

The new police powers, fines and gaol terms in NSW, and around the country, are complex and extreme.

Already we are hearing of our mob in regional NSW fined as a result of these new orders. This is on day one of the new orders.

This is such a dramatic change for our young people to adjust to and they are already too often the targets of police.

If they can’t afford a parking fine, how on earth will they manage $1,000 to $11,000 dollars.

Lastly, Makayla, since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody released its findings in 1991, there have been over 400 First Nations deaths in custody.

Looking at some of the recent cases, why would you be concerned about keeping Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in prisons at this time?

Over the decades our families and communities have lost loved ones due to racist laws and practices that keep our people incarcerated in the thousands.

The system fails and neglects our unwell mob and they die, sometimes at the hands of the workers who were supposed to ensure their safety.

The pandemic has meant that the inquest for my brother has been further put on hold. While we wait for closure, and try and stay strong, we will do everything in our power to stop this tragedy happening to countless other First Nations families.

Justice Health did not have the resources to care for Nathan, who was one person with chronic asthma, let alone multiple people with a respiratory illness.