Stop the Dame Phyllis Frost Expansion: An Interview with Homes Not Prisons’ Karen Fletcher

On 19 March last year, the Andrews government announced a $188.9 million expansion for Victoria’s Dame Phyllis Frost Centre – a maximum security prison for women – which proposes the provision of an additional 106 new inmate beds.

Increasing the capacity of the women’s prison is part of the Labor government’s broader $1.8 billion prison expansion program. It aims to see 2,000 new prisoner beds, which includes the construction of a giant supermax facility in the small town of Lara outside of Geelong.

Indeed, at the moment, the entire country is going through something of a prison boom, with the NSW Liberal Nationals government having recently invested $3.8 billion into an extra 7,000 beds, while the Queensland state government is set to have delivered 4,600 new prisoner beds by 2023.

However, crime rates in general have been on a downward spiral since the turn of the century, which suggests the ever-rising numbers of prisoners nationwide don’t directly correspond to a spike in people breaking the law.

Increasing women inside

Over the ten years to 2019, the adult prisoner population in this country grew by 43 percent, however in terms of women in prison, this saw a dramatic 64 percent rise. And over recent decades, the fastest growing cohort of people being locked up in Australian gaols are First Nations women.

The ten years to 2019 saw the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women inside increase by 95 percent. And last year saw First Nations women accounting for 38 percent of the total female prisoner population, whilst making up less than 3 percent of the overall female populace.

This steep rise in women being sent to prison doesn’t equate to an increase in criminal behaviour. In fact, the vast majority of women in prison have been convicted of minor nonviolent offences, with most coming from disadvantaged backgrounds.

The majority have also suffered some form of gendered violence. Yet, despite this, prison systems nationwide continue to subject women to degrading strip searches, which impact similar to sexual assault, and serve no real purpose.

Homes Not Prisons

In response to the Andrews government announcing its plans to make more space to lock up more women, Homes Not Prisons was launched.

The campaign is calling for the Dame Phyllis Frost expansion to be dropped, and for that money to be redirected into public housing.

Women and trans and gender diverse people who are, or have been imprisoned, and particularly First Nations women, are leading the Homes Not Prisons campaign.

Part of the steering group, Karen Fletcher, the executive officer of Flat Out, has been speaking at recent campaign events. And the group is currently compiling an open letter calling on the Andrews government to divert the funding.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to lawyer Karen Fletcher about the direct link between a lack of affordable housing and prisons, the rising discourse around “therapeutic prisons”, and how Homes Not Prisons will be escalating its campaign this coming year.

The Andrews government announced last March that it’s expanding Victoria’s Dame Phyllis Frost women’s prison.

Karen, why has Homes Not Prison come out so strongly against this plan?

When new cells are built, they get filled. That’s the experience in Victoria.

We’ve had this massive expansion in the number of women being sent to prison and, in particular, Aboriginal women. This is as a result of changes to sentencing, bail laws and the way that parole is administered.

But rather than looking at reforming those laws, the response has been to expand the prison to over 700 beds.

So, the premise there is: when new cells are built, they’re going to be filled?

That’s the experience in Victoria and elsewhere. When you build them, you end up filling them and that just means more people going to prison.

The big problem with that is prison damages people and it damages communities. So, if we have more people in prison, then communities are – and particularly community safety is – going to be damaged.

The other side of our campaign is the enormous expense for the people of Victoria. It’s so much more expensive to build prison cells than it is to build public housing and public homes.

For the cost of building the 106 additional cells at Dame Phyllis Frost, the state could easily build 1,000 public housing units, and more than pay for running intensive support for people in those units.

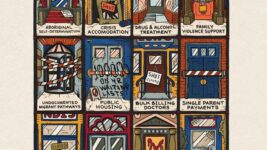

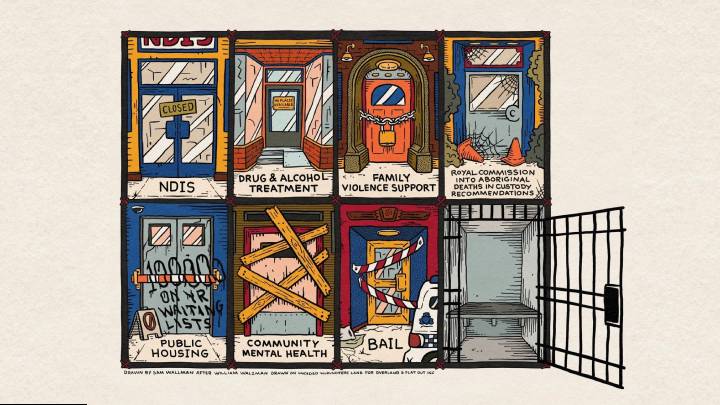

So, it’s also about the massive expenditure on prisons, which is taking away money from housing, but also other essential services, like health, drug and alcohol rehabilitation and mental health services.

Homes Not Prisons is highlighting that the expansion plan includes two new 20-bed “management units” for solitary confinement. Why is this of particular significance?

This is really significant in Victoria, because what we’ve seen is the government arguing that what’s needed is therapeutic prisons.

Over the last decade, arguments have been made that therapy, rehabilitation and health can be facilitated inside prisons.

But people who have experienced prison say that’s not true: it’s not possible to heal in a prison environment, and, particularly, not in solitary confinement.

These two new units are being called management units. But the government is also talking about them as being therapeutic units. And they’ve built these types of solitary confinement facilities in what they call “healing centres”.

There is a growing argument that prisons actually promote healing. And they’re arguing this in terms of Aboriginal people. They’ve been talking about an Aboriginal healing centre in prison.

But those leading the Homes Not Prisons campaign are clear that separating people from their families – particularly women from their kids – their communities and their specialist Aboriginal healing services in the community is causing harm.

Using violence – like strip searching and solitary confinement – is traumatising and the opposite of healing.

So, it’s an important part of our campaign to get the information out that the people who have experienced prison have provided, which is that prison itself is a traumatising experience.

Prison traumatises women. It traumatises their kids, and it often sees children sent to foster care or state care, where they can end up in contact with the juvenile justice system and then the adult system.

What we’re trying to say is it’s not true that prisons are therapeutic.

For a long time, the argument has been that women who don’t have accommodation or suffer trauma in their lives and are struggling with alcohol or other drugs are put in prison for “their own good”.

This is what women involved with the campaign have said: that oftentimes magistrates will sentence women to prison as an alternative to being out in the community homeless.

But this isn’t the case. The women are saying that homelessness needs to be addressed. The trauma needs to be addressed. The alcohol and other drug issues need to be addressed.

Those issues aren’t addressed by putting people in prison, where they’re strip searched.

Prison is essentially a system of violence that separates women from the community, and it continues the trauma they suffer on the outside. It’s not therapeutic.

As you’ve mentioned, the campaign highlights that rather than funding prison expansion, the money could be used to fund more public housing, as well as for the provision of housing first arrangements for criminalised women.

Can you speak on the direct link that investment in these sorts of alternatives has on the broader proposal to expand prisons?

Homelessness has extraordinary links to imprisonment. An extraordinary proportion of people who are sent to prison are homeless when they go in, and a larger proportion are homeless on release.

So, addressing homelessness itself would reduce the need for prisons and the prison population. It’s a very strong link.

There was strong research from AHURI last year that shows concentrating on getting people into secure and permanent public housing is the most effective measure to reduce people’s return to prison.

So, trying to shift this priority in terms of budget and government away from spending on prison and onto public housing – which is secure and permanent accommodation for people – is essential if we’re going to address community safety and crime prevention.

The Dame Phyllis Frost expansion is part of a broader prison expansion project announced by the state Labor government as part of its 2019/20 budget.

This involves $1.8 billion to create 2,000 more prison beds, which includes construction of a large supermax facility.

Whilst this announcement mirrors similar such prison expansion initiatives nationally, it also comes at the same time that crime rates have been trending downwards for the last twenty years.

In your opinion, why is the Victorian government investing heavily in prisons when it would seem the need has long been in decline?

One of the issues in Victoria is that historically we have had a lower imprisonment rate than a lot of other jurisdictions.

That’s due to the struggle over a number of decades by anti-prison activists against privatisation down here and against incarceration rates.

The danger with this massive expansion that has been announced over the last couple of years is that Victoria is going to catch up with the rest of Australia.

The big driver here, as elsewhere, has been politics, as politicians understand that they’re re-election or election chances are increased by emphasising fear around community safety and the use of prisons as a way of addressing that.

That’s along with the incredibly powerful lobby in Victoria, and elsewhere, of the police union and the corrections officers’ union, which are in support of more police and more corrections officers, as a community safety measure.

The push hasn’t been balanced by a strong movement for real community safety, which is only really provided by strong communities, where people are housed, and kids are in a safe situation with their parents.

The big drivers are politics and the police union, which opposes any kind of reduction in budgets for police and prisons.

The police union uses crime statistics, sometimes quite misleadingly, to generate fear in the community about crime, and then put prisons and prison expansion as the only solutions.

So, it’s historically very difficult to get any other view out into the mainstream. And Homes Not Prisons is one of many organisations that are trying to put a different view to the public.

We’ve got another election coming up here in Victoria this year, and it’s extremely important that we get evidence-based information out about what actually increases community safety.

Of course, we’re all concerned to see communities, and kids in particular, safe and to reduce drug, alcohol and mental health problems, but prisons have the exact opposite effect.

Prisons are not a solution to any of these issues.

Last month, Yamatji, Noongar, Wongi and Pitjantjatjara woman Ms Calgaret died in custody whilst living at a reintegration unit of the Dame Phyllis Frost Centre.

How would you say this bears on the issues you’re raising through the Homes Not Prisons campaign?

This is an essential issue. When the number of women being sent to prison increases, the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women increases disproportionately. This reflects the situation around Australia.

Racism is a particular problem in the justice system in Australia, and in Victoria.

When Aboriginal people are sent to prison, their health is more vulnerable, and they’re more vulnerable to die in custody. That’s why we see continuing rates of Aboriginal deaths in custody in Victoria, and around Australia.

Dame Phyllis Frost is a particular issue at the moment. In that prison, we lost Ms Calgaret recently, and a couple of years ago there was the death of Veronica Nelson, whose inquest is going to happen this year. And a newborn baby also died at the centre, not long ago.

This just indicates that the prison is a dangerous place – a harmful place – for women and their children, and it’s especially dangerous for First Nations women.

We’re in a situation where prisons in Australia have long been used as part of the colonisation process.

This country has a long history of imprisoning Aboriginal people, and this isn’t only in prisons. It happened with missions and reservations. It’s a way of dispossessing them from their lands.

This has led to generational trauma, and the process is ongoing with the use of prisons in a racist and colonialist way.

That is resulting in this terrible situation where young women, young men and kids are dying in custody. It goes back to the so-called therapeutic nature of prisons. These places are not therapeutic.

These young women who have died at the Dame Phyllis Frost Centre shouldn’t have. They should have been able to be cared for in their communities.

There should have been housing, health services and support for them to deal with the trauma that they have in their lives as a result of racism and colonisation – not in the prison setting, but in a community setting.

And lastly, Karen, at what point is the Dame Phyllis Frost Centre expansion up too, and what is 2022 looking like for the Homes Not Prisons campaign?

As I said, it’s an election year here, and we’ll be raising awareness around the demand that Dame Phyllis Frost not be expanded by 106 beds within the context of the vote.

We have support from the Greens and the Reason Party’s Fiona Patten. But also, we’re talking to some rank-and-file members of the Labor Party, many of whom agree with us.

We’re hopeful the government will change its mind and not go ahead with the expansion.

Our understanding is, at the moment, there’s construction work going on at Dame Phyllis Frost, but it’s not currently the construction of new cells.

There’s a need at Dame Phyllis Frost for improved visitor and health facilities. And while we have a prison, we’re concerned to see that the women and kids who are there have good visitor and health facilities.

Whilst we would prefer not to have any prison at all, at the moment, it’s there and it does need to be upgraded. But there’s absolutely no need to expand its capacity.

That will be our campaign: to make sure the new cells aren’t built this year. At the moment, the intention is to have those new cells constructed by the end of 2022.

We’re determined to make sure that they’re not constructed.