‘Sugar Slaves’: Australia’s History of Blackbirding

The Queensland sugar industry currently generates $2 billion annually. But, it’s a little-known fact that the industry was built upon the backs of Pacific Island people, who were coerced, deceived and even kidnapped from their islands of origin to work in slave-like conditions.

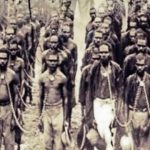

The practice known as blackbirding saw an estimated 62,500 South Sea Islanders sent to Queensland and northern NSW to work in the development of sugar cane, pastoral and maritime industries.

The people came from more than 80 islands in the Pacific. The majority were from Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands, along with people from Papua New Guinea, Tuvalu, Kiribati and Fiji.

Akin to slavery

Technically, these people cannot be referred to as slaves, as they signed contracts – which they couldn’t read – and were paid with what amounted to a small fraction of the market wages of the time. So, the correct term to use is indentured labourers.

However, these people were segregated from the rest of society, unable to speak their own language, and corporal punishment was administered upon them. They were also only provided with a weekly food ration and their hours of work were unlimited.

An estimated 15,000 died within the first year or so of arriving due to European diseases, mistreatment and malnutrition. And when they did die their bodies were buried together in mass unmarked graves, some of which continue to be uncovered today.

From the hardship of others

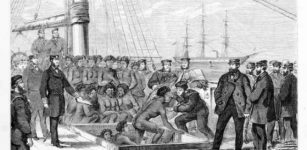

Britain abolished slavery throughout the British Empire, with the passing of Abolition Act in the House of Commons in July 1833. The practice of paying South Sea Islanders a minimal wage was seen as a way around this.

Five pounds a year is what they were paid, while European workers could expect 20 pounds or more. And from 1885, the Queensland government began taking these wages and the indentured labourers were never paid out.

Benjamin Boyd began shipping men out from New Caledonia to work on his properties in NSW in 1847. But, the colonial government of NSW eventually banned blackbirding. The Queensland government, on the other hand, allowed its citizens to benefit from the practice.

Pacific Island people first arrived in Queensland on a ship called the Don Juan in 1863 and they continued to arrive up until around 1901. Much of the success of businessmen Robert Towns and John Mackay is attributed to their use of South Sea Islander indentured labour.

Today, the cities of Townsville and Mackay bear the names of these two notorious blackbirders.

Systemic racism

Then in 1901, the newly appointed federal government of Australia passed the Pacific Island Labourers Act, which sought to deport most of the 10,000 South Sea Islanders, who were still in the country.

The act was part of a package of similar legislation that later became known as the White Australia policy. The is the only time the Australian government has passed legislation to deport a whole group of immigrant people.

Initially, around 700 South Sea Islander people were allowed to remain in Australia. The legislation provided that those who had arrived prior to September 1 1879, were “employed as part of the crew of a ship,” or “possessed certificates of exemption” were allowed to stay.

The South Sea Islanders challenged the move. They even sent a petition to King Edward VII, containing 3,000 signatures. And as opposition to the law grew, the government expanded the categories of exemption.

Funded by their own labour

However, the deportations went ahead, and the majority of the community was sent back to the Pacific Islands they came from between 1906 to mid-1908. Some of them were even shipped to the wrong island.

To pay for the mass deportation the Queensland government took the wages it had confiscated from the labourers, along with the wages of those who were deceased and gave them to the federal government in order to cover the cost of sending them back.

The wages of the deceased were meant to be used to send trade goods back to the islands from which they came from, so as to compensate for their deaths. But, this practice was only ever carried out around 16 percent of the time.

And around 2,500 South Sea Islanders were eventually allowed to stay in Australia.

A call for recognition

Today, the Australian South Sea Islander community numbers around 300,000. Over the past twenty years, community members have been involved in “a call for recognition” – a movement to have the community recognised as a separate ethnic identity within Australia.

In 1994, the findings of the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission led to the federal government recognising the community as a disadvantaged ethnic group. And the state governments of Queensland and NSW have since followed suit.

However, little has changed for the Australian South Sea Islander people, as they continue to face similar disadvantages to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

This marginalised group is suffering the intergenerational trauma produced by the legacy of kidnapping, slave-like labouring conditions, segregation and forced deportation.

At a conference marking the 150th anniversary of the first arrival of South Sea Islander people in Queensland, veteran Australian journalist Jeff McMullen described the practice of blackbirding as the racist exploitation of people of colour, who were taken from their homes with no understanding of what awaited them.

The legacy back home

The practice of blackbirding also impacted the island communities from where these people were taken. In 2013, Vanuatu’s land and mining minister Ralph Regenvanu attended an event held in Brisbane marking the first arrival.

The minister outlined that the issue has had a major impact on Vanuatu, and is a big part of their national identity. He said that the national language Bislama “was developed in the cane fields of Queensland.”

The prime minister of Vanuatu made a speech at a national commemoration event marking the anniversary, in which he called for an apology from the Australian government

But, unfortunately, given track record of successive governments in this country the island nation might be waiting a long time.

The practice of blackbirding and the devastation it caused is yet another chapter in Australia’s checkered past that has been written out of this nation’s history.

But, just like the Frontiers Wars before it, now it seems middle Australia will have to face up to yet another historical injustice.