Supermax Prisons: Doing More Harm Than Good

Supermax prisons are the most secure and highly monitored form of incarceration there is. These super-maximum security facilities are designed to house “the worst of the worst:” your mass killers, top-level gangsters, gang rapists and, more so these days, terrorists.

A judge doesn’t sentence an offender to a supermax facility. Either an inmate has been found too hard to handle at another lower security gaol, or else, an offender has been convicted on a terror-related charge.

Supermax prisoners can often be kept in solitary confinement for up to 23 hours a day. They can have restrictions placed on how many people they associate with, and prohibitions are often placed on undertaking programs and activities.

To be sent to supermax, a detainee must be designated by the commissioner as either an “extreme high risk restricted inmate” or a “national security interest inmate,” as under the provisions of section 15 of the Crimes (Administration of Sentences) Regulation 2014.

An extreme high risk restricted offender is given an A1 rating. These inmates were traditionally classed as the most dangerous. However, as of 2004, national security interest inmates, or convicted terrorists, are given an AA rating, which places them at the top level of security classifications.

Historical hardcore incarceration

The prototype of the supermax prison is said to be Alcatraz federal penitentiary, which was opened in August 1934. Located on an island in San Francisco Bay, Alcatraz was where inmates who caused too much trouble in other gaols were sent.

And due to its island location, Alcatraz was said to impossible to escape from.

However, the concept of the supermax prison really caught on in the States in the mid-1980s. In 1984, Illinois’ Marion federal penitentiary was the only facility that could have been labelled as super-maximum security, after it went into long-term lockdown in October 1983.

By 1999, there were 57 supermax prisons, or control units, across 34 states in the US. The popular push to establish these high-priced facilities was triggered by the stabbing of two corrective services officers in separate incidents at the Marion facility.

In Australia, an early example of a supermax-style facility was the Katingal prison unit that was opened within Sydney’s Long Bay correctional facility in 1975. Known as the “electronic zoo” due to its artificial environment, Katingal was designed to house the most problematic NSW prisoners.

The Katingal facility, which had no windows, was closed a few years later, after the Royal Commission into NSW prisons recommended that it did so. It found that the extreme sensory deprivation the inmates were subjected to was an abuse of their human rights.

Antipodean control units

Currently, in Australia, there are a number of small supermax units at larger correctional facilities, such as the 8 cell unit at Tasmania’s Risdon prison, the 12 cell supermax section of the ACT’s Alexander Maconochie Centre, and G Division at Yatala labour prison in South Australia.

And then there’s three main supermax facilities. There’s the Special Handling Unit at Western Australia’s Casuarina prison, and the 40 cell Olearia unit in Victoria’s Barwon prison that opened in August 2016.

But, the crème de la crème of Australian super-maximum security facilities is the High-Risk Management Correctional Centre situated within the walls of the Goulburn gaol complex.

A prison within a prison

The Goulburn supermax facility was opened by then NSW premier Bob Carr back in 2001. The prison cost around $20 million to complete. And today, it is costing taxpayers $550 a day to detain each inmate within the confines of the centre.

At the time it was opened, Mr Carr described the type of inmate who would be imprisoned at the facility, as those that “cannot, or will not, fit into normal rehabilitation programs while in gaol.”

“These are the psychopaths, the career criminals, the violent standover men, the paranoid inmates and gang leaders,” Carr continued. And he went on to add that the facility “will try to break the cycle of violence, so these prisoners can safely be placed back into the mainstream prison system.”

However, the rehabilitative aspect of the facility that the former premier alluded to isn’t something that people readily associate with Goulburn supermax. These days, it’s renowned for being the last stop for inmates who’ve been put in the too hard basket – those too far gone to change their ways.

Those inside

Australia’s most notorious mass murderer Ivan Milat is currently detained at the Goulburn supermax facility. Milat killed seven people between the ages of 19 and 22 – most of whom were foreign backpackers – in NSW’s Belanglo state forest in the early 1990s.

While convicted murderer and Brothers for Life founder Bassam Hamzy is also serving time at the super-maximum security facility. Hamzy had previously been held at Lithgow prison, where he was running an elaborate drug network, as well as having organised two kidnappings, from his cell.

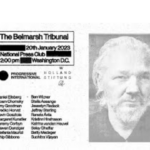

However, these days, the majority of inmates at the supermax facility in Goulburn are convicted terrorists. As of April last year, 30 of the 48 prisoners incarcerated within the facility were there for terror-related offences.

The practice of locking up convicted terrorists in the one correctional facility is a controversial one. Proponents believe it reduces the risk of these inmates radicalising others, whereas critics point out that it can actually lead to increased extremism within the same group.

Aggravating the underlying issues

Supermax prisons are the most extreme end of the punitive justice system. And whilst many of these inmates have committed heinous crimes, the deprivations they’re subjected to inside these control units, might be seen as exacerbating behaviours it’s meant to prevent.

These sorts of facilities can have a devastating effect on an individual and lead to long-term trauma. And the majority of these prisoners are already suffering extreme psychological issues when they arrive.

While some of these inmates, such as Ivan Milat, will never see the light of day again, many will end up back on the streets at some point. And if they’ve been subjected to years of mistreatment on the inside, then it might be the whole of that community that will have to suffer the consequences.