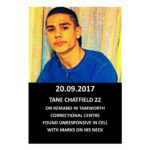

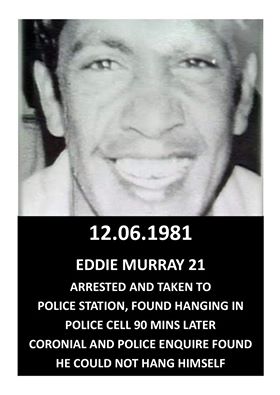

Suspicious Circumstances: Detained Eddie Murray Was Not in a State to Hang Himself

Eddie Murray was found dead, hanging in a cell at Wee Waa police station at around 3.00 pm on 12 June 1981. The 21-year-old Gamilaraay man had been detained by officers about an hour earlier for public drunkenness, under now repealed laws which claimed to criminalise what was no longer an offence.

Murray was an accomplished footballer prior to his supposed “suicide”. On the day following his death, he was set to travel to Warrang-Sydney from the lands of the Gamilaraay nation, in an area now referred to as northern NSW, to join the Redfern All Black’s Rugby League tour of New Zealand.

There was no evidence that Eddie was suicidal. Mr Murray’s parents consistently claimed their son had been picked up by police and murdered, while NSW police sergeants Page and Moseley testified to finding him hanging from a blanket in his cell.

The Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody couldn’t reject the theory that death by other means was “a possibility”, but found it ”improbable”, and went with hanging. Although, a later body examination located a fracture to his sternum, which likely occurred just prior to death.

Eddie’s death in custody was hardly the first case of an Aboriginal person dying under suspicious circumstances whilst being detained, however subsequent campaigns calling for an end to these tragedies have always looked back to his case as a catalyst for change.

“That is murder”

“A government medical officer found that young Eddie’s blood alcohol level was so high he was incapable of standing for too long unassisted,” explained Murri elder Ken Canning, “let alone tie an intricate knot and suicide.” And he added that being so drunk was no crime whatsoever.

NSW barrister Robert Cavanagh QC represented families at the Royal Commission. In 2015, he said he’d been “naïve” to trust the commission’s investigation, because of NSW police involvement. “It astounds me they are allowed to investigate themselves in these instances,” he told the Australian.

“In the long run, it was found that he was killed by person or persons unknown,” Mr Canning told Sydney Criminal Lawyers. “Unless the police handed out keys to the cells to the general public, it would have had to be a policeman.”

Eddie’s parents who dedicated the rest of their lives trying to bring about justice for their deceased son, had his body exhumed in 1997. And an examination by a forensic pathologist determined a ruptured sternum – a blow to the chest – had occurred right before his death.

“This was never ever pursued,” long-term First Nations activist Canning asserted. “Two or three policemen were found to be lying at the inquest, once more no follow up. The police killed Eddie intentionally, that is murder.”

Young lives taken

Eddie’s death in custody had national impact, along with the 1983 death of John Pat, which occurred in police custody in the WA town of Roebourne. According to Canning, it was the young age of both men that “disgusted people all over the country”.

And it must be remembered that just a month ago, in the remote NT Aboriginal community Yuendumu, two police officers entered a house, and one of them allegedly gunned down unarmed Warlpiri man 19-year-old Kumanjayi Walker.

NT police constable Zach Rolfe has been charged with Kumanjayi’s murder, which is significant, as it’s the first time an Australian police officer has been charged with murder over a First Nations death in custody since the colonisation of the continent began 231 years ago.

That government inquiry

“In 1983, the Committee to Defend Black Rights (CDBR) was formed,” Canning recalled. The group, along with Eddie’s parents Arthur and Leila, mounted a six year campaign that led to the Royal Commission, which investigated 99 First Nations deaths in custody over a ten year period.

Incidentally, Canning emphasises that many believe then PM Bob Hawke only “caved in” to the national investigation to coverup his involvement in killing off a chance of establishing substantial land rights for Indigenous people in a deal Professor Gary Foley can fill you in on.

Two key commission recommendations were that the arrest and incarceration of First Nations peoples should be sanctions of last resort. Most of the 339 recommendations made by the Royal Commission’s final report, which was handed down in 1991, have simply been ignored.

Back then, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people made up 14 percent of the adult prisoner population in this country. Today, 28 years on, they now account for 28 percent of people inside. While, the last census shows First Nations people are only 2.8 percent of the general populace.

The fight continues

“The whole shame of this is both of Eddie’s parents did not live to see justice and they fought so hard,” Mr Canning underscored. “They gave their all for their son’s justice and in its own way they are a victim of the state’s killings.”

But the Indigenous Social Justice Association (ISJA) and Fighting in Resistance Equally (FIRE) are continuing his parent’s struggle for justice for those who have lost their lives in the custody of NSW police or Corrective Services NSW via the Black Deaths in Custody (BDIC) campaign.

“Both ISJA and FIRE realise the governments of this country will never implement the recommendations of the Royal Commission,” Canning continued. “Instead, we are demanding that all members of police or prison staff involved in a killing or death be stood down immediately.”

The BDIC campaign delivered a declaration of its five reform recommendations to NSW parliament in May last year. These include independent inquiries, along with investigations carried out by Aboriginal authorities themselves, and the release of First Nations peoples for nonviolent crimes.

Another reform that Canning emphasises is that when a death in custody does occur, “the relevant minister invariably takes to the media within an hour and states, ‘no suspicious circumstances’”. This is “preconditioning the public to the outcome they want.” he concluded. “This has to stop.”