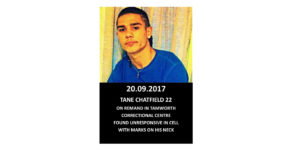

Suspicious Circumstances: Tane Chatfield’s Alleged Suicide Doesn’t Add Up

As Colin Chatfield puts it, his son was about to be released from prison in relation to charges he’d been remanded over for two years, as eight witnesses couldn’t identify him during his trial as being involved in the armed robbery he’d been accused of.

So, when Corrective Services NSW reported that Tane Chatfield had attempted suicide via hanging, it didn’t ring true. The 22-year-old Gamilaraay, Gumbaynggirr and Wakka Wakka man his family saw leaving the courtroom the day prior was in good spirits over the prospect of being released.

Tane was found unconscious in a Tamworth Correctional Centre cell on the morning of 20 September 2017. Two days later, he passed away in hospital. Corrective Services NSW announced that there were no suspicious circumstances surrounding his death, but his family doesn’t buy it.

Indeed, Tane’s family took photos of his body in the hospital, which revealed he’d suffered extensive injuries. And on sighting the photos, NSW Greens MLC David Shoebridge remarked that his injuries were “inconsistent with death by hanging”.

And while corrective services told the public that the incident marked the first Aboriginal “suicide” in its custody since 2010, the Guardian’s Deaths Inside count outlines that Tane’s passing marked the sixteenth Aboriginal death in police or corrective services custody in this state since 2008.

Not the official version

“The photos that we took of him show he was all busted up. He had skin under his nails. He had scratch marks on his body,” said Colin Chatfield. “There were bruises all over his face, a busted lip, and a practically broken nose and jaw.”

“He would have been released when he finished his trial,” he further told Sydney Criminal Lawyers. “There were eight people who gave evidence and couldn’t identify my son as being the culprit. And he didn’t make it to court the next day.”

The Chatfield family has maintained that the circumstances surrounding Tane’s death are certainly suspicious. On the evening prior to him being found unconscious, Tane apparently had a seizure and was hospitalised, while his cellmate was suddenly removed from the cell they’d been sharing.

The cellmate alleged shortly after the incident that he’d heard screams coming from the cell where Tane was being held on the morning he was found unconscious. And he also said that while all the other inmates were out in the prison yard, Tane had been kept back.

Regarding the claims that there was nothing untoward about his son’s death, Chatfield said, “Corrective services investigating corrective services, well, they cover their own. If we had an independent team coming in to investigate, there would be a different story altogether.”

“Dead all along”

Mr Chatfield also expressed concerns about his son being kept alive on life support equipment, with the presumed aim of preserving his organs. He recalled that in the hospital, Tane was being kept under a cold sheet, with a fan blowing and ice containers placed beside him.

As soon as the family entered the hospital room, the doctor asked about the young man being an organ donor and whether they would donate his organs. And according to Chatfield, as soon as they said no, the doctor switched off the equipment.

“In the moment we said no to his organs, she turned off the machines and pronounced him dead,” he added. “He was dead all along.”

Too early to call

Murri elder Ken Canning explained in the weeks following the incident that the conflicting stories circulating about Tane’s death were typical of a death in custody. He said in the first instance he was told the man was hanging in his cell, but in the next version, he was unconscious on the floor.

And Canning criticised authorities for announcing there was nothing suspicious about the young man’s death just hours after it occurred. The long-time activist continues to call out corrective services’ habit of pronouncing nothing abnormal about such deaths straight after they happen.

Rather than putting out a statement immediately following the death of an Aboriginal detainee, Mr Canning recommends that corrective services should wait until a thorough investigation has been carried out. And he underscores that the inquiry should be conducted by an independent body.

Race specific dehumanisation

Right now, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people make up 28 percent of the adult prison population in this country, while First Nations people only account for 2.8 percent of the overall Australian populace.

This is despite the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody recommending that both arrest and imprisonment be used as sanctions of last resort. And this disproportionate incarceration has led to over 400 First Nations deaths in custody since the inquiry tabled its 1991 report.

Mr Chatfield has spent time behind bars. And he says that Aboriginal inmates are subject to round the clock abuse from officers and they’re “set up to fail” inside, while things like seeing a doctor takes an extra long time for Indigenous prisoners.

“It’s pretty hard. We get treated like the bottom of the chain,” he made clear. “We get treated worse than those prisoners were being treated in Guantanamo Bay.”

Ending the lives lost

On 22 October, Mr Chatfield shared the circumstances surrounding his son’s death with those gathered at the Blak Deaths in Custody (BDIC) forum that was held at NSW parliament. The campaign is led by the Indigenous Social Justice Association and FIRE.

The BDIC campaign is calling for police officers and prison guards to be held to account, for the release of First Nations inmates who are being incarcerated for nonviolent crimes, and for an end to the disproportionate number of Indigenous people being held on remand.

As well as Tane Chatfield’s death, BDIC also remembers those of David Dungay Junior, Rebecca Maher, Eric Whittaker, TJ Hickey, Patrick Fisher, Nathan Reynolds and Mark Mason. All unique incidents that are related due to the suspect circumstances surrounding them.

Mr Chatfield explained to those gathered at NSW parliament that his family are waiting for the inquest into his son’s passing. “We are still waiting. It’s been over three years,” he said. “And we’ve still got no answers.”