The Australian Government Abandoned Assange Long Ago

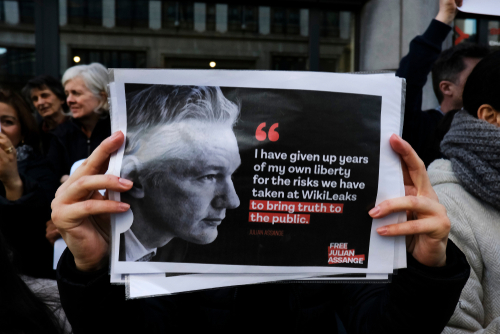

Australian citizen and Wikileaks publisher Julian Assange has been detained on remand, and in isolation, at London’s notorious Belmarsh maximum security prison for the last fortnight.

His mother, Christine Assange, tweeted on Monday that so far, he’s been denied visits from his lawyers.

Following the recognised journalist’s eviction from the London Ecuadorian embassy, his arrest by UK authorities and his immediate conviction over breach of bail, this country’s PM Scott Morrison stated that while Assange will get the usual consular service, he’ll receive no “special treatment”.

While this reaction is disappointing, it’s hardly surprising. This has been the same recurring lack of response from the government since Assange was first arrested by UK police in December 2010 to be extradited to Sweden over allegations that have since been dropped.

After Assange lost his UK Supreme Court extradition appeal in May 2012, he sought asylum in the Ecuadorian embassy not to steer clear of Swedish prosecution, but to avoid the very real prospect of subsequently being extradited to the US, where, it was then thought, he could face execution.

When Assange took refuge under Ecuadorian jurisdiction, it was already well-established that the Australian government had abandoned its national. Indeed, the deputy sheriff was well aware that their senior on the other side of the Pacific was well-ticked off by the exposure of Manning’s leaks.

Implicit approval

“It’s a bit delusional for the government to pretend this is a regular consular matter, when it has never been anything of the kind,” former Australian Greens Senator Scott Ludlam told Sydney Criminal Lawyers.

“This is the opposite of support: it is tacit hostility to be looking the other way while an Australian citizen is prosecuted for being a publisher,” continued Mr Ludlam, who, whilst in parliament, repeatedly fought for the government to give a just response to Assange’s plight.

The digital rights activist explained that what’s most significant about the impact of Assange and Wikileaks was their model of publishing the bulk of primary source materials, as this was “an enormous breakthrough in bypassing traditional media gatekeeper roles”.

As for the events of two weeks ago, Ludlam said, “it appears that the revocation of Mr Assange’s asylum protection, arrest by UK authorities and the immediate unsealing of the US DOJ indictment, all taking place in a matter of hours, was highly orchestrated between the three governments.”

What extradition order?

Despite Wikileaks publishing an email in February in 2012 written by geopolitical intelligence platform Strator’s chief security officer Fred Burton stating, “we have a sealed indictment on Assange”, the Australian government long denied any knowledge of its existence.

When Mr Ludlam in 2012 asked about the indictment – which would have included an extradition request – then Senator Chris Evans said the government wasn’t aware of it. In 2013, former Senator Bob Carr further told Ludlam that the government hadn’t tried to ascertain whether it existed.

However, in mid-2018, when Assange’s UK-based lawyer Jennifer Robinson applied on behalf of her client for a new passport, a DFAT employee said it was their understanding he mightn’t be issued with one as he may be subject to an arrest warrant for a “serious foreign offence”.

Moves like Pontius

But, the Australian government washed its hands of Assange right from the start. Then prime minister Julia Gillard described his 2010 publishing of four major leaks of classified US documents as “illegal”. Although, the AFP subsequently concluded it wasn’t.

Former Senator George Brandis mused out loud in 2011 that Assange may have been involved in soliciting the leaks from Manning. And it’s thought his line of thinking could have influenced US authorities in pursuing the hacking offence that was recently revealed on unsealing the indictment.

While in 2013, following remarks made by prosecutors at Manning’s trial implying that Assange engaged in espionage, then foreign minister affairs Bob Carr said the journalist was no longer a concern of this country, as his case didn’t “affect Australian interests”.

Calls for his murder

Following the Manning leaks, multiple public calls were made in North America for Assange to be assassinated. These included those from former senior advisor to the Canadian prime minister Tom Flanagan and former Alaskan governor Sarah Palin.

On receiving a petition requesting he take action over Flanagan and Palin’s calls, then foreign affairs minister Kevin Rudd stated in 2011 that as the pair no longer represented their respective countries, there was nothing he could do, so any concerns should be taken up with the US and Canada.

And in response to 2012 questioning from Australian Greens Senator Adam Bandt, reining PM Julia Gillard didn’t respond to his mention of calls for Assange “to be hunted down” or his possible execution, she simply stated “the government cannot interfere in the judicial processes of other countries”.

Arbitrarily detained

The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) found in December 2015 that the UK and Sweden had been arbitrarily detaining Assange, firstly, when he was held in isolation at Wandsworth prison and then his subsequent “house arrest and confinement at the Ecuadorian embassy”.

The WGAD requested the two countries assess their positions on Assange “to facilitate the exercise of his right to freedom of movement in an expedient manner”. The UN body considers its opinions legally-binding under international human rights laws.

When Mr Ludlam questioned former Consular and Crisis Management Division first assistant secretary Jon Philp about the decision at a 2017 Senate Estimates hearing, he was told the Australian position was that the WGAD’s opinion “is not binding on states”.

Philp further stated that “where an Australian citizen has been caught up in legitimate legal processes of any country, we accept that it is the right of that country to pursue them under their courts and in their laws”. And then attorney general George Brandis backed up his comments.

Further charges in store

Assange will be appearing in Westminster Magistrates Court on 2 May via video link for proceedings relating to his possible extradition to the US on a charge of conspiring to commit computer intrusion, which carries a maximum of 5 years imprisonment.

However, his long-term legal adviser, human rights barrister Geoffrey Robertson, has warned that the maximum penalties relating to offences that he could subsequently be charged with after arriving in the United States could add up to 45 years imprisonment.

It came to light last February that the Australian government finally issued Assange with a passport in September last year, but it seems somewhat unlikely that as he awaits sentencing for breach of bail in the UK, this is going to be of much use any time soon.

While government officials in this country continue to assert he’ll be accorded the due process he’s should be afforded under the UK criminal justice system, the fact that he hasn’t been allowed any visits from his lawyers so far doesn’t bode well.