The Extralegal Christmas Island Brutality Regime: Interview With Refugee Action Coalition’s Ian Rintoul

Victoria police pepper sprayed refugee activists out the front of the Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation (MITA) centre on 3 May, as 12 detainees were hauled off by the Australia Border Force to be transferred to the Christmas Island immigration facility.

In a statement, the ABF said that the dozen captives were being transferred as their visas had “been cancelled due to being a risk to the community”, while the Asylum Seeker Research Centre confirmed at least one of the transferees was a refugee.

Since July 2013, the Rudd government commenced sending refugees arriving by boat to offshore detention centres, vowing that they’d never be settled. Then, as the Abbott government took power that September, then immigration minister Scott Morrison unleashed Operation Sovereign Borders.

Morrison’s policy continued mandatory offshore detention, commenced turning back the boats, and the current prime minister lorded it over a brutal dehumanising regime as he destroyed the lives of some of the globe’s most vulnerable people, until handing over reins to Peter Dutton to have a go.

Deporting resident foreigners

While he was still in the role of immigration minister, PM Scott Morrison made amendments to the character test in section 501 of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth), so that noncitizens who are sentenced to at least 12 months prison time are automatically deported to the country where they were born.

The 12 months can include multiple sentences, suspended ones, time in residential rehabilitation or a mental health facility. This has resulted in the deportation of around 1,000 people annually since 2015, the majority of whom have been long-term residents, often over committing minor offences.

In terms of refugees, who can’t be sent back to their countries of origin due to risk of harm – the principle of nonrefoulement – they have their visas cancelled and are then held in indefinite detention.

In January, there were 124 immigration detainees, who’ve been inside for over 5 years.

Following the Federal Court finding in late 2020 that detaining individuals indefinitely for no reason was illegal, the Morrison government promptly passed laws in May last year, that clarified that the government can legally keep noncitizens in indefinite detention due to nonrefoulment reasons.

The Christmas Island dehumanisation centre

Morrison reopened the detention centre on Christmas Island in early 2019, because he was annoyed parliament had passed laws that he didn’t agree with, which allowed sick refugees detained offshore long-term by his government to come to Australia to receive much-needed medical treatment.

The majority of detainees on Christmas Island are deportees, or 501ers as they’re commonly known. But there are refugees and asylum seekers held there too. And for the past couple of years, the authorities at the centre have been treating those held there to extreme brutality and violence.

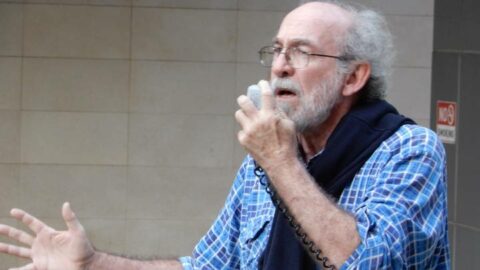

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Refugee Action Coalition spokesperson Ian Rintoul about the refugees who continue to be locked up by Morrison, how the results of the pending election will affect them, and the brutality Australia is meting out on what he refers to as “Devil’s Island”.

On 3 May, protesters attempted to prevent the transportation of 12 detainees from MITA detention centre, who were bound for Christmas Island immigration detention.

The ABF has since stated they were all being transferred because their visas had been cancelled “due to being a risk to the community”. It’s also been confirmed that at least one of the transferees was a refugee.

In your understanding, Ian, what happened last Tuesday? And is the timing of the operation so close to a federal election a little suspect?

It is a little suspect. The government has tried on numerous occasions to inject the issue of asylum seekers and refugees into the campaign. So, there has to be a question mark over the timing.

However, it also needs to be said that the detention centres are full, and we’ve been expecting some transfers from mainland detention centres to Christmas Island for some time, which has been hampered because two of the major compounds on the island were badly damaged by riots and fires in January.

As I understand there were people transferred on 3 May, and there was a valiant effort made to prevent the transfer. But these people have been successfully moved from MITA to Christmas Island. And it definitely involved the transfer of some refugees.

The government always raises the issue of threats to the community. But, in many cases, it’s not made completely public because the convictions that these people have been responsible for don’t involve anything that could be deemed a threat to the community.

The problem at the moment is that anyone who’s convicted of a crime is liable to have their visa cancelled. Some are automatically cancelled if they’re sentenced to a period of 12 months prison.

The final Medevac refugees were released from the Park Hotel in March. Following that, the final eight asylum seekers remaining in the hotel were released last month.

Around 230 refugees have been released into the community since December 2020, without explanation as to why. And last month, there were huge Palm Sunday Free the Refugees protests across the country.

So, when we’re talking about freeing the refugees now, who are we talking about? And are there broader issues being raised in this campaign?

The fact is there are still at least six transitory persons in detention, according to the government’s own figures. We know of three of those people.

One of those is broadly associated with the Medevac cohort, as they were brought here early this year for medical treatment and remain in BITA. “Free the refugees” applies to those people.

More generally, there are around 280 people remaining in detention, who are boat arrivals.

That also covers a number of complex categories: some whose visas have been cancelled, some whose visas have been denied on character and security grounds, some people who have failed asylum seeker applications and either continue appeals or who’ve run out of appeals.

It needs to be said that those people actually include Afghan refugees who are still in detention, as they have failed to win visas on the basis that it was safe to return to Kabul and Afghanistan.

Now, those issues are being raised with the government. It’s obviously patently absurd that Afghans should continue to be held under whatever visa category or as an asylum seeker, as its very clear that they can’t ever be returned to Afghanistan. Kabul is never safe.

The other grouping immediately does still relate to the people who are on Nauru and PNG. The fact is there are about 105 to 108 on Nauru and 111 or so in Papua New Guinea. They still remain victims of the government’s offshore detention policy.

They are not free in any sense. In New Zealand, the resettlement process doesn’t include anyone in Papua New Guinea, and it’s not going to ensure that everyone in Nauru is going to be resettled in NZ even by the end of three years.

But the campaign also does relate and has become increasingly aware of the whole situation of the so-called criminal deportees, the 501s.

As I have said, a number of them are either asylum seekers or refugees, whose visas are cancelled. It’s an issue that has barrelled along for some time that we have taken up from time to time, because it’s impossible to ignore.

The 501s who are in immigration detention are also victims of a racist immigration policy. They are only in detention because the Migration Act allows the government to discriminate against them even though they have served their time according to the criminal justice system.

But then the Migration Act allows the government, because they are noncitizens, to hold them for indefinite periods of time.

That’s something which the refugee movement, and also the wider Australian community is becoming more aware of, and I’m quite sure it will become a growing feature of the movement’s demands on the Australian government.

Then PM Kevin Rudd committed to a policy of refugees arriving by boat not being settled in Australia in 2013. Although it was Scott Morrison who turned “never being settled” into his own mantra that he still basically abides by.

But if you look at the reality of what’s occurred since those times, it’s very different to what the government claimed then, and still tends to portray.

Can you speak on that point?

Kevin Rudd has his own peculiar and not so entirely honest take on it. But there is no doubt that Rudd’s policy, which has been described as the Pacific Solution Mark II, did mean that people who attempted to come by boat to Australia would be sent to Papua New Guinea and would never be allowed to be resettled.

That was then built on by the subsequent Coalition government, with Operation Sovereign Borders, which was marked by the boat turn backs to Indonesia, then Sri Lanka, and, of course, it was compounded by the horrendous conditions that developed on Manus Island and Nauru quite deliberately.

This also had consequences on the mainland because, under the policy introduced by Rudd and Gillard, it meant that people who had arrived by boat but hadn’t been sent to Manus or Nauru, were precluded from applying for protection until a couple of years ago.

So, you’ve still got people who arrived in Australia in 2012 and 2013, only just now being allowed to make protection applications and are still awaiting the outcomes.

They have been subjected to horrendously long periods of resettlement time. And, of course, people who are still on Nauru and Papua New Guinea can’t seek protection, expect for now there is the US deal and Canada is open for private sponsorship, as well as the New Zealand deal.

But we still have a situation where a very large number of people who were brought from Manus and Nauru into Australia have got no resettlement possibilities in Australia, and people on PNG and Nauru are precluded from resettlement in Australia.

So, this is one of the big unfinished pieces of business that the refugee movement has with any incoming government.

There are almost 1,200 people who were on Manus and Nauru brought over for medical treatment to the Australian mainland but remain in community detention or on bridging visas.

So, at the moment, they’re precluded by both parties from actually getting bridging visas in Australia.

Most of the detainees on Christmas Islander are 501ers, who are mainly former residents that have had their visas cancelled and are being deported on character grounds. There are also some refugees and asylum seekers locked up with them.

There are numerous reports detailing the brutality the Australian government is meting out upon Christmas Island detainees. In your understanding, what’s going on there?

Christmas Island has been the Devil’s Island of the Australian detention regime forever. It was established as a behavioural management centre. It’s a punitive detention centre. People sent there go through a graded process to ensure behavioural compliance.

They’re not transferred from the introductory compound to the next compound until they have proven themselves to be compliant immigration detainees. And that remains the case.

It’s the reason why there have been a series of uprisings and riots on Christmas Island over the last few months, which haven’t gained any kind of publicity.

Christmas Island remains the quintessential example of the lack of transparency and accountability that applies to the detention regime right across Australia.

The fact is once people are in that detention regime, whether it’s Serco or Border Force who has control of those centres, the people who are in them are completely at their whim.

People have reported that Serco or Border Force are able to place people in prolonged periods of isolation without any kind of accountability or any way of making any kind of complaint.

So, Serco and Border Force remain judge, jury and executioner inside the detention regime.

On Christmas Island, there’s particular brutality with the use of the emergency response team, which exists in all of the detention centres.

But the Christmas Island footage is where we see riot squad fully decked out with their shields and batons actually systematically beating the detainees. It’s an absolute scandal.

It would not be tolerated in the criminal justice system, but it happens with impunity in the immigration detention system, because there is no oversight or accountability or system of regulation.

It remains completely unregulated, so it does mean that Border Force and Serco are able to act with impunity inside that regime.

You’ve touched on my next question there, but I’ve seen multiple clips on social media, not just on Christmas Island but in onshore centres as well, involving this one procedure being used at different times.

It consists of about six to eight detention centre security guards marching into a room wearing military-style gear, including helmets, and carrying large clear shields.

These guards are just there to remove one unarmed detainee from an area. Sometimes they’re the only person in the room.

What’s going on with the way that Australian authorities are treating detainees in immigration centres?

It’s a very good question. We only know from the information we get from those clips, which are from the detainees inside. But the fact is it’s become a routine procedure that Serco uses and Border Force sanctions for any kind of removals.

Even in Yongah Hill, we’ve seen examples of that procedure used against individuals just being shifted from one compound to another or being taken from a compound to an interview with a Serco manager or Border Force officer.

That’s just one example of what I was mentioning previously about the militarised nature of immigration detention. And there’s no way for detainees to make any systematic complaint about that kind of behaviour.

When people are assaulted for no reason, there’s no mechanism to record those assaults or make complaints about them.

The number of times I or others have been involved in actually trying to get state police or federal police to respond to assault complaints have gone nowhere, because state police aren’t willing to investigate.

Then the federal police say it’s a state police responsibility, and then Border Force comes back saying it’s been investigated, and the complaint is finished.

It can be for many kinds of things. It even happens to people who have mental health problems.

People can be removed from one area of a compound to where they’re going to be effectively moved into solitary confinement, so they’ll actually use the same mechanisms, which is overwhelming and often results in trauma and assaults on the individual that’s being transferred.

The same kind of transfer mechanism was used when people were being taken out of their individual rooms in MITA last week to be put on buses for transfer to Christmas Island.

As I said, it’s the type of thing that would not be tolerated in the criminal justice system. But because it’s the Migration Act and because people are noncitizens, this kind of behaviour, mistreatment and brutality has just become part and parcel of the detention regime.

And lastly, Ian, as the federal election is looming, there are still refugees and asylum seekers being detained both here and offshore.

During their first public debate together, Morrison raised the tough on refugees issue, and Albanese underscored that he was deputy PM when mandatory offshore detention first came into play.

So, as a long-term refugee rights advocate, what’s the best outcome we can hope for in this coming election in terms of the nation’s immigration regime? Indeed, is there a better outcome based on the major parties?

We need to get rid of Morrison, because, although the policies are very close between the majors, a Labor government will get rid of temporary protection visas and will give those people permanent visas.

They’ve also said they will take the Biloela family back to Biloela, although they haven’t actually said whether they’ll give them a permanent visa yet.

It’s a small but not insignificant difference. Everyone involved with the refugee movement wants to see an end to the Morrison government.

But, it would be foolish to have any kind of illusions that we are about to see any fundamental changes beyond what I’ve mentioned with the TPVs with the Labor government.

Albanese has made a particular point of that. Kristina Kenneally has made quite similar and striking points around Labor supporting sending back the boats and offshore detention.

So, if anyone were to arrive by boat in Australia, they’d either be turned back or subject to offshore detention.

Even if all the prospects of Canada, the US resettlement and the NZ resettlement are actually accepted, the best figures are that 505 people will not have any kind of settlement out of that arrangement.

This is especially so for those in Papua New Guinea, who have no prospect of resettlement even in New Zealand.

So, there’s an enormous amount of unfinished business. And in that respect, the best thing that can come out of the election is an end to the Morrison government.

But we need an activated refugee movement because there remains an enormous amount of unfinished business that we are still going to have to fight for regardless of what happens on 21 May.

We obviously hope some of the independents have much better things to say about refugee policy.

The Greens, of course, have much better things to say about refugees and they’ve got bigger voices in parliament, whether in the House of Representative or the Senate. That’s the best sort of circumstances we can hope for.

But it’s going to depend on there being a very active refugee movement after the 21st of May if we are going to see fundamental changes.

There is so much we still have to push for or the Migration Act will simply remain a piece of racist legislation that systematically discriminates against asylum seekers, refugees and noncitizens.

It doesn’t guarantee the right for people to actually seek protection or to be able to live in the community while those claims are being made.

So, there’s a lot of unfinished business regardless of who wins.