The Five Eyes Alliance Is Watching You

Australian prime minister Malcolm Turnbull met with his Canadian, UK and New Zealand counterparts for a security briefing at the UK National Cyber Security Centre on April 18. Along with the US, the four countries represented at the meeting make up the Five Eyes intelligence alliance.

At the high-level meeting of the secretive data sharing alliance, the PMs discussed increasing Russian cyberattacks in the US and the UK, the alleged Syrian government chemical weapons attack and the nerve agent attack on a Russian ex-spy and his daughter in Salisbury.

Also, on the agenda was a plan for the five countries to step up economic contacts with Pacific nations in order to curb Beijing’s growing influence in the region, which is feared could lead to China increasing its military surveillance and intelligence operations.

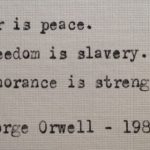

During a doorstep interview after the meeting, Turnbull stated several times that the Five Eyes alliance is all about maintaining the rule of law. However, critics of the alliance warn that it’s a global surveillance arrangement operating above the law, without any transparency.

All pervasive

The Five Eyes alliance grew from US and UK signals intelligence sharing arrangements during the Second World War. Under the 1946 UK/USA Agreement, these arrangements were formalised and broadened to include Australia, New Zealand and Canada.

Thirty years passed before the governments involved even acknowledged the existence of the alliance. Indeed, to this day, the governments of all five countries remain tight-lipped about the legal frameworks governing it.

But, these days, the Five Eyes nations aren’t just gathering signals data. As retired Canadian brigadier general James S Cox outlined in a 2012 paper, the alliance is also gathering and sharing defence, human and geospatial intelligence.

In Australia, ASIO is in charge of gathering security intelligence, the Australian Secret Intelligence Service is on human intelligence and the Australian Signals Directorate is charged with acquiring the signals intelligence.

And an appendix to the UK/USA Agreement indicates that the five nations comprising the alliance are to share their data “continuously, currently, and without request,” and this applies to “raw” data, as well as intelligence that has already been analysed.

Exposing their reach

Public awareness of the secretive alliance grew when the 2013 Edward Snowden revelations revealed the extent of the mass surveillance programs that were being carried out by the US National Security Agency (NSA), along with the agencies of the other Five Eyes nations.

The 20,000 documents Snowden leaked showed that the NSA was collecting millions of US citizens’ telephone data, had tapped directly into the servers of nine internet companies, including Google and Facebook, and was collecting and storing 200 million text messages globally a day.

Amongst the files the former NSA contractor distributed were documents that related to a 2012 top secret presentation that was shared with the other nations in the Five Eyes partnership, which revealed that the NSA had hacked into 50,000 computer networks around the globe.

Watching me, watching you

David Vaile, co-convenor of the UNSW Cyberspace Law and Policy Community told Sydney Criminal Lawyers® last August that while internally nations might have laws that prevent the government from accessing its citizens’ data, the Five Eyes Alliance opens up ways to get around these restrictions.

The Five Eyes allows for the gathering and sharing of foreign intelligence data. Mr Vaile explained that under these arrangements the British had been surveilling US citizens in ways US intelligence agencies couldn’t do themselves.

“There may be programs the Australian government has in place that require a warrant – for instance, for the actual interception of content – that some other participants can bypass,” Mr Vaile said.

“So, the query is whether that goes around in a big network, or it can be used to break those national protections,” he continued.

Since October 2015, 21 Australian law enforcement agencies have had warrantless access to the stored metadata relating to the phone calls, emails, text messages and internet sessions of all Australian citizens. However, access to the content of such communications is restricted.

Newly disclosed documents

In July last year, Privacy International and the Yale Law School’s Media Freedom and Information Access Clinic filed a lawsuit against the NSA and the US State Department seeking access to records relating to the Five Eyes alliance, under the Freedom of Information Act.

Privacy International have recently received a limited number of documents, which included the 1961 General Security Agreement between the Government of the United States and the Government of the United Kingdom.

This agreement has raised concerns over the Five Eyes alliance’s third party rule that prevents the disclosure of information shared between agencies to third parties. Privacy International has pointed out that this includes oversight bodies, which means the agencies operate without any scrutiny.

The UK-based privacy non-profit also got its hands on a 1998 agreement that extended the 1966 Pine Gap agreement. One of Australia’s main roles in the Five Eyes alliance is gathering and sharing intelligence data that is collected at the secretive spy base just outside of Alice Springs.

Established in 1966, Pine Gap is today staffed by both US and Australian citizens and is involved in the collection of intelligence data from around the Asia/Pacific region, as well as being used by the US military to locate targets for drone operations.

However, only a few documents relating to the Five Eyes alliance have ever been released and for the most part the knowledge of how the intelligence sharing operates is limited.

The war on encryption

In June last year, the attorney generals and security ministers of each of the Five Eyes nations met in Ottawa for a two day meeting where they raised concerns over the widespread use of encryption that they claim is fostering terrorism.

A communique released by the alliance states that “encryption can severely undermine public safety efforts by impeding” law enforcement.

Then the Turnbull government announced the following month that it wants to enact laws that allow Australian security agencies to gain access to the private encrypted messages stored by social media and technology companies, like Facebook and WhatsApp.

A spokesperson for Australian defence minister Marise Payne said last month that the legislation that will create backdoors into encrypted communications is in its “advanced stages of development.”

And it can be assumed that if Australia manages to gain access to citizens’ encrypted messages that the information will be shared across borders, and the other members of the Five Eyes alliance will be right behind this nation in further invading any privacy that their citizens have left.