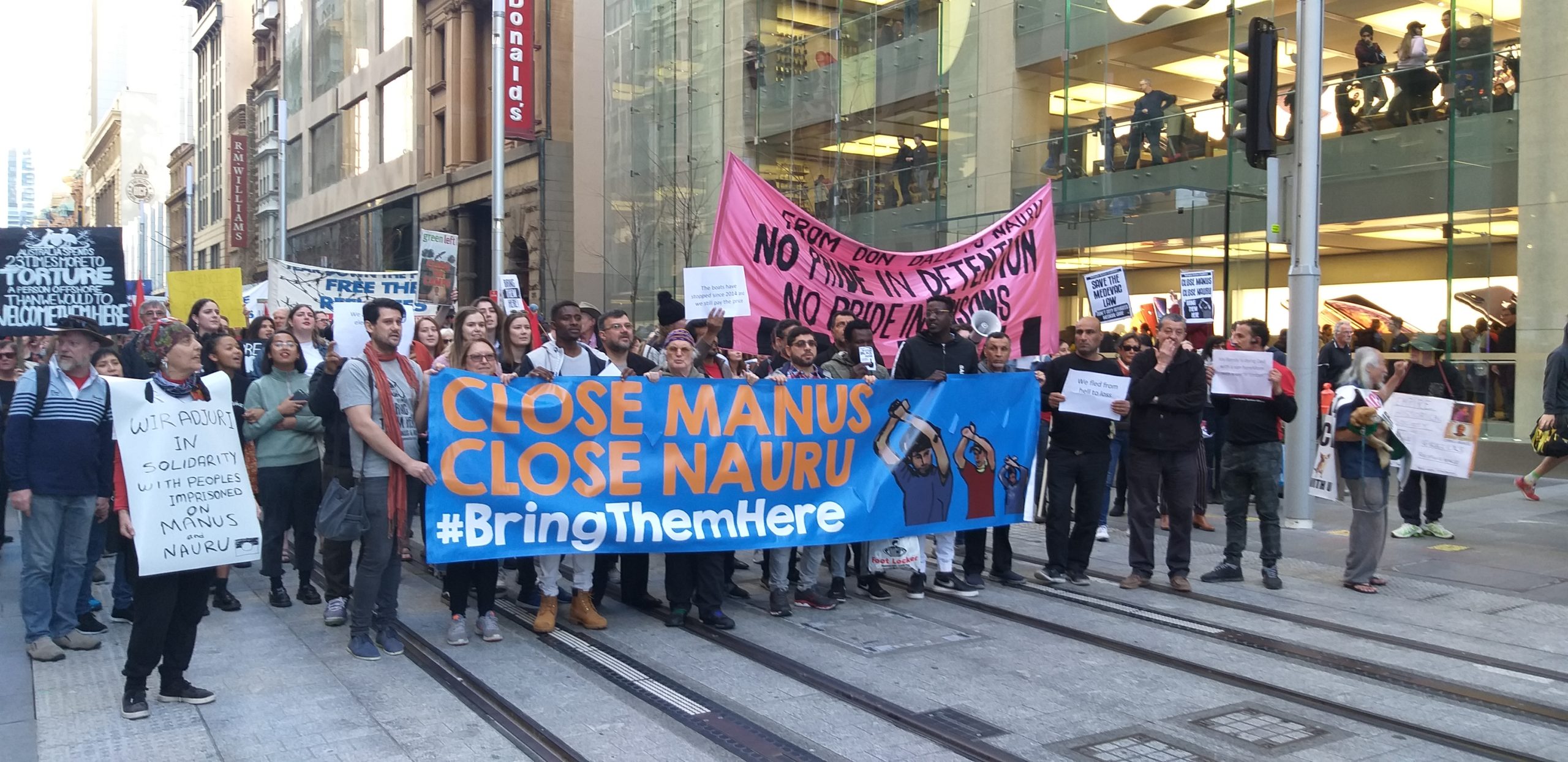

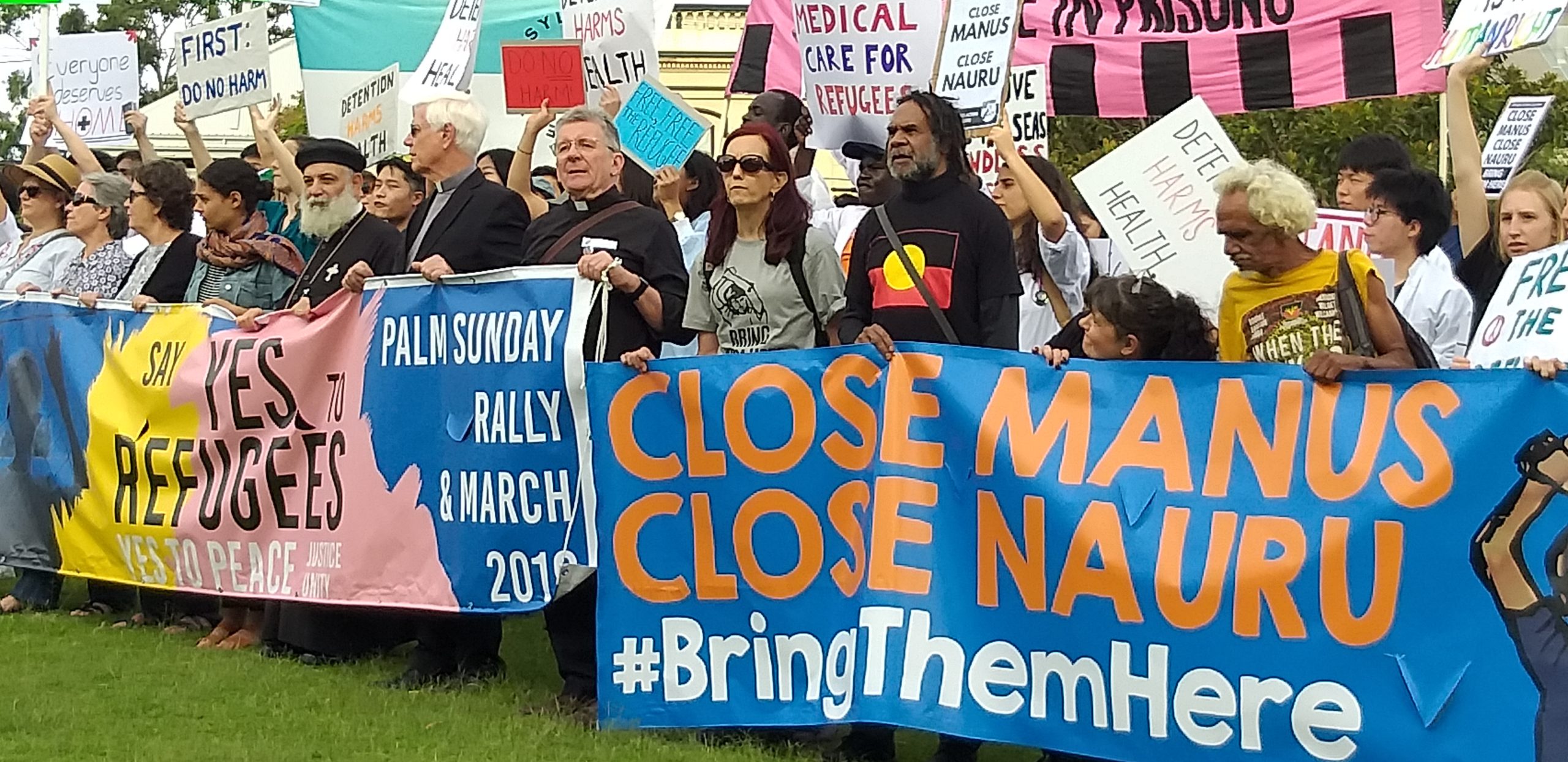

The Government Continues the Slow Torture of Refugees, In Our Name

With the new year having ticked over, it must be comforting for Liberal Nationals politicians, such as Scott Morrison and Peter Dutton, to begin 2020 knowing that they have offshore detainees exactly where they want them: acting as beacons of an ongoing system of deprivation and inhumanity.

The past year had proven problematic for pollies of their ilk, as the passing of the Medevac laws, not only showed a parliament out of step with its government, but the measures also displayed a modicum of compassion, which is not the type of image those governing want to display.

Indeed, this new year marks seven since the Australian government started locking people up on the soil of smaller, poorer Pacific island nations to act as a warning to those fleeing persecution that if they arrive by boat, they’ll be relentlessly tortured for their troubles.

The mandatory offshore detention regime has seen this nation imprison a total of 3,127 asylum seekers over its time in operation. It’s cost taxpayers billions of dollars, as well as siphoned off some of their humanity, while it’s cost the detainees their bodies, minds and lives.

Right before Christmas, the Morrison government finally got what it wanted: the repeal of Medevac. And this has left over 180 detainees, who’d already been transferred here for medical reasons, to remain locked up in hotel rooms across the country without any chance of receiving treatment.

Alternative places of detention

“These people were brought here as patients to receive treatment but are being treated as criminals despite having committed no crime,” said UNSW senior research fellow Dr Rebecca Reeve. And the majority of those who’ve been transferred haven’t received treatment, the econometrician added.

Just on Christmas, it came to light that a group of around 40 offshore detainees had been held at the Mantra Hotel in the Melbourne suburb of Preston for over a month. And while they’d been brought to the country from Manus Island for treatment under Medevac, they’d received none.

Vocal refugee advocate Jane Salmon has visited the men at the hotel. She told Sydney Criminal Lawyers that visitors are not permitted to directly provide the detainees with clothing donations. And any food given to them must be consumed on the spot or thrown out.

And this is obviously a situation that’s being repeated at locations around the nation, as groups of offshore detainees are being held at various “alternative places of detention” with the reason behind it – the provision of medical treatment – being simultaneously denied.

Dr Reeve added that in the wake of the Medevac repeal, the future of those brought to Australia is uncertain. However, what is clear is that the excessive use of security in the form of numerous physical searches is “traumatising” them and has left some “reluctant to leave their rooms”.

Covering the costs

Released early last month, the At What Cost report outlines that the remaining 535 people still caught up in the Australian offshore detention regime that was established in 2013 would cost taxpayers $1.2 billion if their detention continues for the next three years.

This is because the cost of detaining an innocent asylum seeker in another country costs around $573,000 a year, which contrasts with $10,221 annually to house a person in the community on a bridging visa.

“We are seeing taxpayer money doled out on a very expensive form of abuse,” Ms Salmon made clear. And she mentioned a long list of how the money could be better spent. It included on the current fire crisis, switching to renewables, helping First Nations youth and raising Newstart.

And the offshore detention system doesn’t just cost Australians monetarily. According to Salmon, the public are paying for the slow torture of these people – 83 percent of whom have been assessed as legitimate refugees – in various other ways.

“It rebounds on our international reputation, our humanity and creates precedents for human rights abuse among voters, as well as immigration detainees onshore and in every institution from hospital to school to aged care to work,” the rights advocate set out.

Slow drip detention

“The people offshore remain in limbo. Continuous uncertainty. Arbitrariness of the treatment meted out,” Ms Salmon further explained. “Some refugees who came on the same boats were settled in Australia.”

The refugee rights advocate outlined that the refugee selection process was utterly random and factors such as qualifications, religion, languages spoken, as well as health and skills didn’t play much of a role in the assessment. “Some very talented people have been driven mad,” she added.

And it should be remembered that driving the detainees insane is the unspoken aim of the offshore detention regime. It’s the implied threat behind the asylum seeker deterrence advertising campaign then immigration minister Scott Morrison launched upon the globe’s poor in 2014.

Back then, when asylum seekers were sent to the offshore detention centres on Nauru and Manus Island, a video of Morrison used to greet them. In violation of international law, the current PM would state that even if they had a valid claim, they would “not be resettled in Australia”.

“If you choose not to go home,” the evangelical Christian set out to those who’d risked their lives on boats escaping persecution, “then you will spend a very, very long time here.” And for the 500-odd still in detention all these years later, no truer words have ever been spoken.

No signs of letting up

Towards the end of 2018, Australians successfully launched a campaign demanding that the kids still held in offshore detention be removed. These calls were made amid reports of children as young as 10 attempting to take their own lives, while others had developed a rare psychological disorder.

But, the removal of all child detainees doesn’t reveal a government bereft of its inhumanity. In actuality, a new Australian government funded transit detention centre was opened last April on the outskirts of Port Moresby, which now houses detainees deemed not to be refugees.

“Many asylum seekers have been locked up in the Australian-built Bomana Immigration facility under isolated, concentration camp like conditions, trying to force them to agree to return to their place of origin,” Ms Salmon concluded.

“No phones. No access by families. Insufficient calories. Beatings. Harassment.”