The Increasing Militarisation of Australia and the Cold War With China Effect

The twenty year war in Afghanistan is coming to an end on 11 September. That is at least from the perspective of the western allied forces that have been stationed in the Central Asian region since the US-led invasion that toppled Taliban rule commenced in October 2001, just days after 9/11.

The somewhat futile question as to whether it was all worth it is currently being asked, as the war was ostensibly about preventing the region from continuing as a hotbed for Islamic terrorists, yet, as western forces retreat, the Taliban is now seizing control of key districts.

Indeed, in a somewhat foreboding move, along with aiming to remove our remaining 80 troops, the Morrison government has also shut down the Australian embassy in Kabul.

Afghanistan was our nation’s longest war. However, as Australia retreats, according to defence minister Peter Dutton, we are already on something of a war footing, as the threat now lies in the Indo-Pacific region, with the specific foe being China.

While talk of a war with the East Asian giant is nothing new, its tempo has been picking up, especially since Dutton took over the war portfolio in late March.

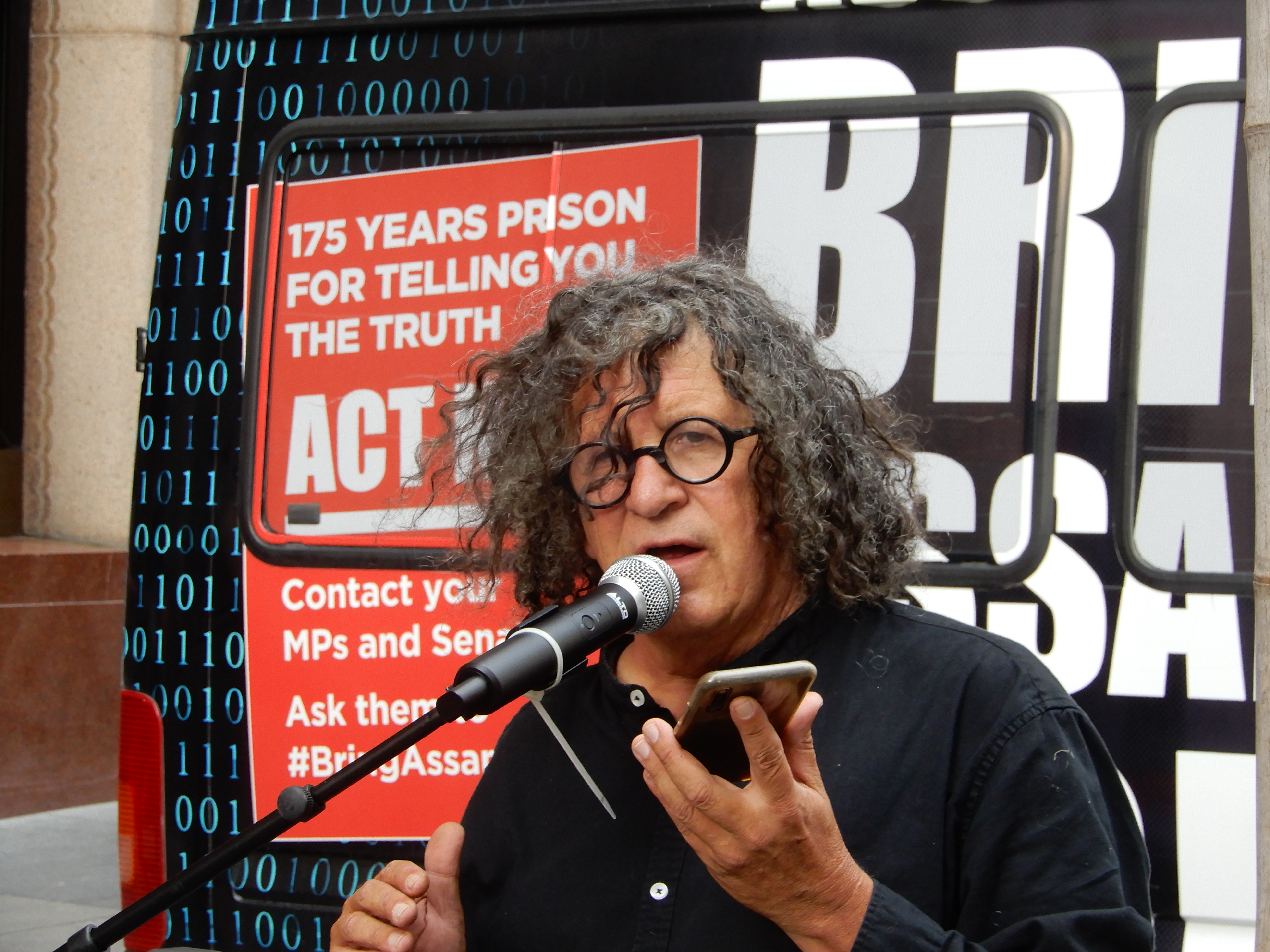

However, a long-term antiwar campaigner has suggested that rather than actually aiming our country’s arsenal at Beijing, the Coalition has really got its sights on establishing a cold war situation with China that will benefit its continuing agenda of militarising Australia.

Same agenda, different enemy

“It’s not just Peter Dutton as defence minister,” remarked antiwar activist Jacob Grech, “now that Barnaby Joyce is again deputy PM, he’s used his first speech to talk about building a stronger Australia, which was in response to the C-word, but he didn’t use the C-word.”

“Nobody actually wants a war with China,” the 3CR radio presenter continued. “What is even more important than the war, are the rumours of it, as this is enabling a whole lot of security measures and, of course, spending in defence.”

With the pivot to the Indo-Pacific, Dutton has indicated that the threat of Middle Eastern terrorism has subsided. However, the national security legislation that was a hallmark of the war on terror-era is continuing to be churned out, with further rights-eroding bills before parliament.

While this time last year, PM Scott Morrison announced $270 billion in defence spending to be rolled out over the next decade to build up our war capacity. The 2020 Force Structure Plan includes investment in submarines, frigates, combat aircraft and reconnaissance vehicles.

The shift to a war economy

In response to the question regarding the two-decade-long war in Afghanistan being worth it, Grech replied that what the response depends on is what is meant by “worth it”.

“Was it worth it for the people of Afghanistan? No. Was it worth it for the Australian troops? No,” he pointed out. “But was it worth it for the war machine? Probably. It was the most profitable war that Australia has been involved in.”

The activist further explained that the Afghan War was unprecedented in terms of military expenditure going back as far as the Second World War. While our engagement in the conflict has served to advance the “hidden agenda” of Australia moving towards “a war economy”.

The fact that the United States has an economy based on war has been well understood since the 1960s. The US military industrial complex – the defence forces and the arms industry – has long shaped that nation’s policy. And Grech posits that Australia is sailing towards a similar arrangement.

“We want to become a major weapons supplier,” Grech added. “It’s a stated objective of government to double our defence exports and to rebuild our engineering framework in terms of defence exports. We can’t make white goods or vehicles, but what we can do is military equipment.”

And coupled with all this, is an increasing reliance on the defence industry to fund tertiary research, which has been fuelled by successive governments’ neoliberal policies. Grech rattled off a list of instances involving arms and military contracting companies funding specific university research.

A dangerous cabal

However, even though he doesn’t believe the Morrison government is deluded enough to contemplate seriously taking on Beijing, the activist warns that beating the war drums in relation to China is a risky practice, especially as the decision to go to war is still in the hands of a few ministers.

Known as war powers, the decision on whether Australia enters into a conflict with a foreign nation rests with the National Security of Committee of Cabinet, which means the rest of parliament, and, in turn, the rest of the nation has no say in it.

The National Security Committee is currently made up of Scott Morrison, Josh Frydenberg, Marise Payne, Peter Dutton, Simon Birmingham, Karen Andrews, Michaelia Cash, and Barnaby Joyce.

“Now we also have Barnaby Joyce, who, as deputy prime minister, is on the National Security Committee, so that’s only going to beef up the talk on China even further,” Grech added, “whereas McCormack was almost a dove on the issue.”

A burgeoning military state

“We are creating a society – whether it is intentional or incidental – where the military are playing a greater and greater role in the everyday life of Australians,” Grech warned Sydney Criminal Lawyers.

“That’s from COVID responses – the troops we saw on the streets for the first lockdown – to education and vaccination roll out.”

The antiwar campaigner is not alone in calling out the increasing militarisation of public life in this country.

Former diplomat Bruce Haigh has warned of the federal Coalition’s increasing reliance on the military. He’s pointed to the defence forces being charged with the vaccine rollout and bushfire relief, as well as Abbott having turned the Australian Border Force into a paramilitary organisation.

The Coalition has also enhanced the capability of government to deploy ADF troops in respect to assist state law enforcement in dealing with civil emergencies and unrest. Then AG Christian Porter oversaw the passing of 2018’s Defence Call Out Bill, as well as a similar 2020 bill for reservists.

“The military is a bigger and bigger part of our everyday lives. And the military’s main focus, as assistance defence minister Hastie said around Anzac Day, is the application of lethal violence,” Grech concluded.

“So, every time we are looking at other issues and areas where the military are involved – whether it’s with education or vaccine rollout – we have to remember that their main application is lethal violence.”