The Inhumanity of Australia’s New Offshore Detention Centre

Papua New Guinea authorities arrested 52 offshore detainees previously held on Manus Island in August last year and incarcerated them in the purpose-built Bomana immigration centre. The facility is part of a large prison complex that goes by the same name on the outskirts of Port Moresby.

Opened in April last year, the $24 million centre was funded and built by the Australian Home Affairs Department. And although it’s been reported to be run solely by the PNG Immigration and Citizenship Authority, it’s also been asserted that it’s Canberra-run.

Bomana is the end of the line for certain asylum seekers. Those locked up there had been deemed non-refugees, either via assessment or not. And the centre is designed to be so extreme as to force detainees into giving up hope, despite having spent years prior in immigration limbo.

And that’s exactly what happened to the men sent to the isolated facility, with no outside contact. The conditions were so torturous that after years of refusing, most signed up to being sent back to their countries of origins.

Although, since doing so, they’re still being housed in Port Moresby not able to be returned as yet.

And as of last week, authorities can hail the operation a complete success, as the final 18 men were released. This was only after some tinkering from rights groups, so these men were offered resettlement in a third country, rather than being forced to return to the land from which they fled.

Employing the techniques of war

“The Bomana detention centre was built by the Australian government for the express purposes of holding the Manus people, who’ve been given negative refugee assessments in Papua New Guinea,” explained Ian Rintoul.

“It’s a deliberately built facility to hold people in an effort to coerce them into signing to go home and deporting them,” the Refugee Action Coalition (RAC) spokesperson told Sydney Criminal Lawyers.

And in relation to how the immigration facility manages to coerce detainees in such an efficient manner, Mr Rintoul likened the circumstances within Bomana to something you might expect to find in “prisoner of war camps from the Second World War”.

The long-time refugee advocate said that detainees were denied communications with the outside world, including legal representation. They were withheld medication and phones. While the water inside was too hot for showering and the thin mattresses provided, lay directly upon the floor.

“They were kept on starvation rations,” Rintoul added, “so everyone who has come out of Bomana has lost between 10 and 15 kilograms.”

The final cohort

The remaining detainees were moved from Manus Island to Port Moresby beginning in August last year, with the final 25 arriving in November. And 52 of these men subsequently ended up in Bomana. Indeed, nine of them had already been approved for Medevac transfer to Australia.

According to Rintoul, the men weren’t given reasons for their incarceration, but it was known that only those deemed negative were sent to Bomana. And the conditions soon led to most agreeing to be repatriated, as they reasoned possible imprisonment in their country of origin would be better.

And last Thursday, 23 January, saw the final 18 asylum seekers released from the Bomana detention centre, after they agreed to third country resettlement, which was not an offer made to detainees that agreed to leave earlier.

“We tried to get messages in to tell people to sign and come out. We attempted various measures, but none of them had been forthcoming,” Rintoul outlined. “The final 18 were released on the basis of them signing to be part of the US resettlement deal, under the auspices of the UNHCR.”

A fresh gulag

Most Australians remain unaware that during the rising calls to end offshore detention, amid the successful campaign to bring the children on Nauru to Australia, and while the enactment and later repeal of Medevac occurred, the government has been intensifying detention for some.

The Bomana immigration centre is part of the 2013 Regional Resettlement Agreement between Australia and PNG, which allows for the ongoing processing of asylum seekers who arrive in this nation’s waters within the borders of another poorer country.

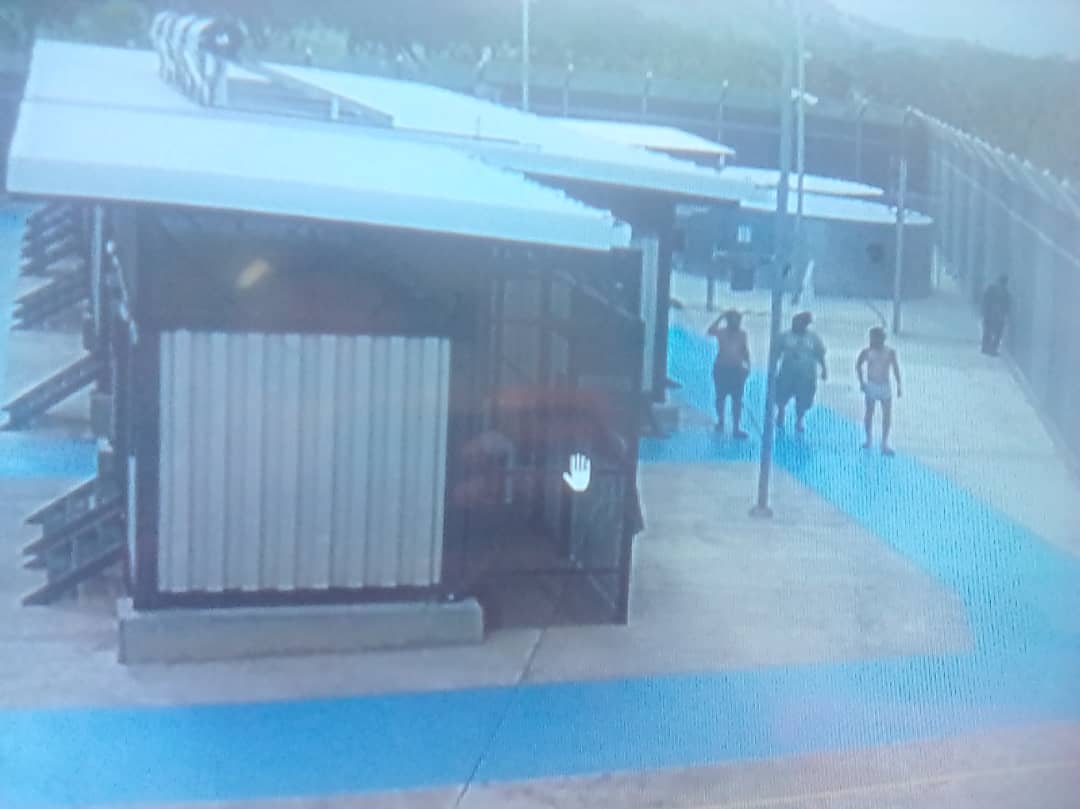

The specially built facility began its operation on 2 April last year. And it has the capacity to hold around 50 detainees, within its 25 rooms, with two individuals in each. These rooms are divided up between five separate compounds fenced off from one another.

“The Australian government has overall control of the centre, as it does every other aspect of the people who they’re responsible for sending to Manus in the first place,” Rintoul made clear, adding that Canberra is “very aware of the circumstances in which people were being held”.

The RAC spokesperson further explained that some of the employees at the facility are ex-Australian federal police. And the people who own the company that are running Bomana are also former AFP employees.

The gift that keeps on giving

As for what Bomana will be used for now that all the Manus Island asylum seekers have been released, Rintoul is clear that it’s likely the Papua New Guinean government will continue to use it in the same manner. But, this time, with asylum seekers who arrive in its own country.

PNG prime minister James Marape warned in mid-January that foreign nationals who entered his country without permission and refuse to leave will be thrown in the Bomana centre, which, for the most part, is unused at present.

“There’s a Filipino and three Bangladeshi citizens who are now in the Bomana facility,” Mr Rintoul explained. He said that keeping it open for the purposes of using it in a similar vein is what the PNG government seems to have in mind.

“But, I suspect it will only be like that as long as Australia is paying for the upkeep,” he concluded.