The People Win: Dutton Won’t Be Removing Refugee Detainees’ Phones

A significant victory was claimed by the Australian campaign to uphold the rights of wrongly detained refugees in this country, when Senator Jacqui Lambie announced last Friday that she’ll be voting against depriving immigration detainees of contact with the outside world.

The outcome is noteworthy because Lambie didn’t make any backdoor political deals in coming to her decision. She threw her vote open to the public, asking what they thought. And of the over 100,000 people who got back, an overwhelming 96 percent asked her to vote against it.

Set to be voted down in the Senate this week, the Migration Amendment (Prohibiting Items in Immigration Detention Facilities) Bill 2020 was all about removing mobile phones from those in immigration detention, as well as expanding the search and seizure powers of officers.

Despite the usual nasty rhetoric coming from the department to justify why these people should be cut off from the rest of humanity, Lambie made clear that detainees aren’t organising “riots” on phones, but rather they’re texting “friends and family” and watching “YouTube videos about cats”.

Credit must also be extended to the hundreds of thousands in the community – the supporters, civil society groups and politicians of all persuasions – who ensured that all immigration detainees won’t be deprived of this vital lifeline, including the Medevac transferees hauled up in hotels.

A victory inside

“I would like to express my sincere appreciation to all the amazing people who voted no to what Jacqui Lambie created,” said 34-year-old Kurdish refugee Mostafa Azimitabar. “And I’d also like to thank Jacqui Lambie for supporting us on this and letting us have our phones.”

“Sometimes I feel my phone is alive,” the long-term detainee continued. “I can be in touch with my family and friends, first of all. And also, I am in touch with my lawyer and some doctors,”

“I feel I am not alone. I don’t feel homesick. And it helps me not to give up.”

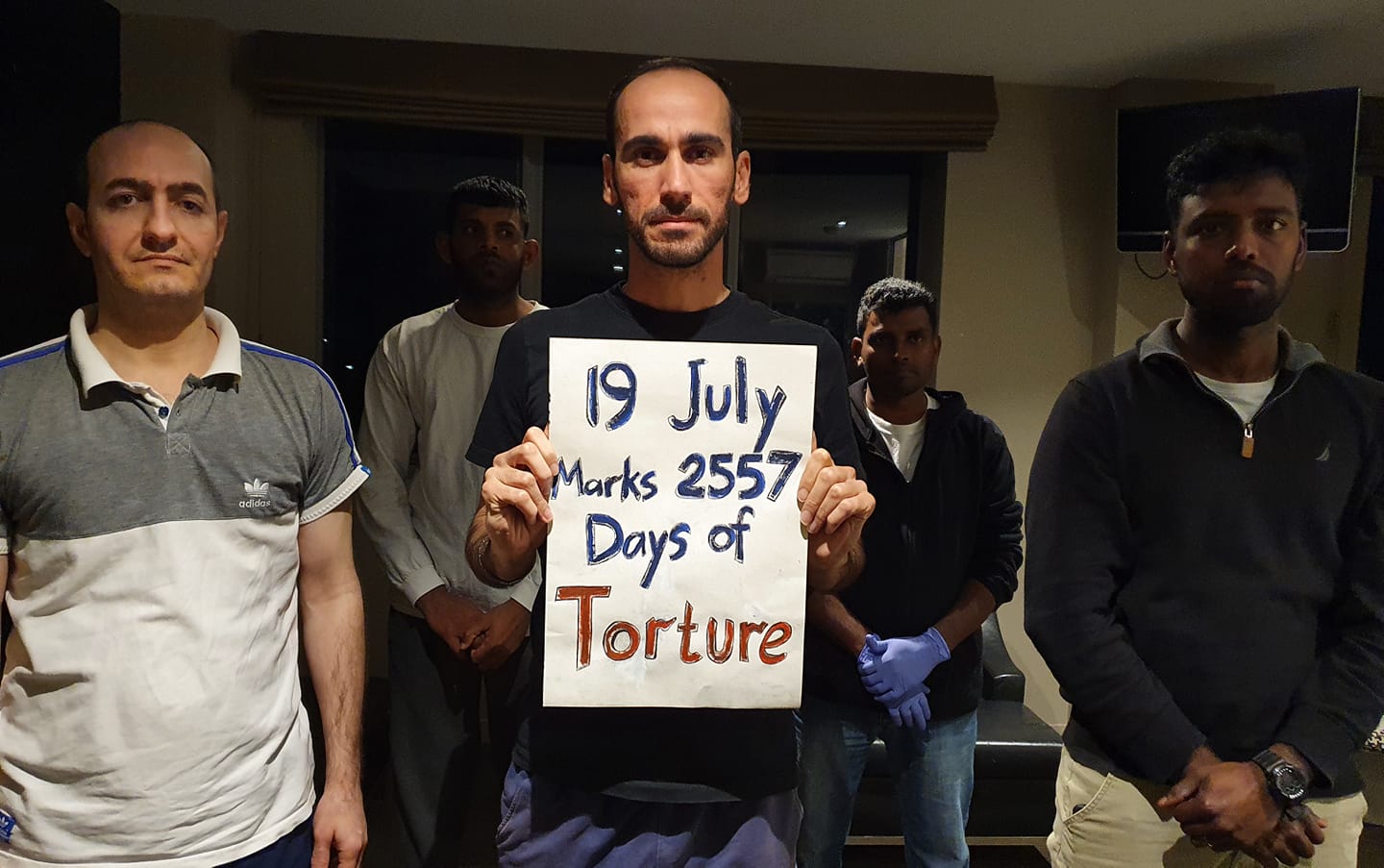

Mostafa, or Moz, is currently being held in Melbourne’s Mantra Hotel, along with around 60 other former offshore detainees, who came to Australia for treatment after two doctors assessed it as necessary, and the minister checked and then gave approval, under the now revoked Medevac laws.

Indeed, Moz and other rights advocates both inside and outside detention, ran a successful campaign on 1 September that involved calling the office of acting immigration minister Alan Tudge to tell him that confiscating refugees’ mobile phones wasn’t on.

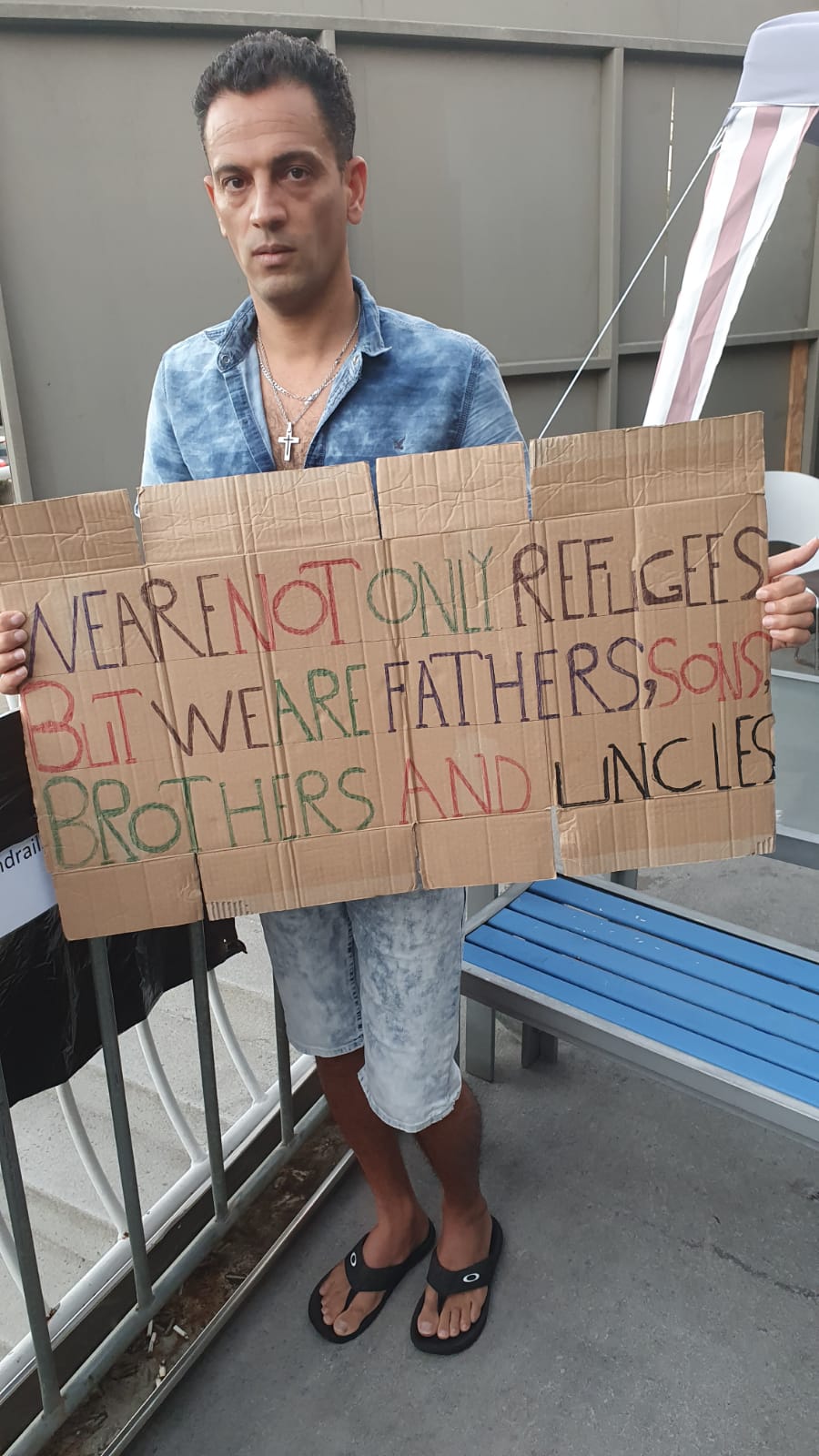

“This is a small victory. It means that the power of the people is stronger than the politicians,” Moz told Sydney Criminal Lawyers. “And these people who wanted us to keep our phones, I am sure they want us to be free.”

Itching to deny them

Dressed up in the scare tactic rhetoric of minister Tudge’s second reading speech on it, and its numerous provisions, the Prohibiting Items in Immigration Detention Facilities Bill doesn’t overtly indicate that mobile phones and internet-capable devices are its main target.

But considered alongside what had come before, its aim is obvious.

Back in February 2017, then immigration minister Peter Dutton and the Australian Border Force launched a new policy that aimed to confiscate the mobile phones of everyone in immigration detention.

Prior to the enforcement of this prohibition, the National Justice Project obtained a temporary injunction, which the not-for-profit legal service followed up with a class action that culminated in the Federal Court ruling in June 2018 that the department couldn’t confiscate detainee’s property.

The Federal Court initially knocked back a Dutton-led challenge to the temporary injunction in August 2017, so the minister then went about introducing the first version of the prohibiting items legislation in September that year, which simply went on to lapse.

Then in May, when federal parliament met for three emergency sitting days to deal with legislation that couldn’t wait until after the pandemic, Dutton and Co made a renewed attempt to bring about laws to confiscate refugees’ phones.

Life-saving devices

“More than 150,000 voices from across Australia called on the Senate to take action, and today we congratulate the senators for listening,” said National Justice Project director George Newhouse, who successfully brought the class action against Dutton’s initial phone ban.

“Mobile phones save lives every day,” the legal service’s principal solicitor continued. “They are a legal, emotional, social, and cultural lifeline without which the government could silence and punish people seeking asylum with impunity.”

Newhouse explained that minister Dutton is trying to take away phones “from the innocent men, women, and children who he has detained”. And this would not only deprive them of vital communications with loved ones, but also cut them off from their legal representation.

“I believe that Priya, Nadesalingam and their two children would be in Sri Lanka today if they had not had their mobile phones with them on the night that the guards stormed their room in Villawood Immigration Centre,” Newhouse maintained.

Also known as the Biloela Tamil refugee family, Priya, Nadesalingam and their two Australian-born children were about to be covertly deported by plane last August, when they were able to contact supporters via their phone, which led to a last minute judicial reprieve.

Now, the family are deplorably being detained at Scott Morrison’s Christmas Island facility.

Release them into the community

The failed mobile phone confiscation bill appeared mid-pandemic at a time when there was a rising focus upon the former Manus Island and Nauru offshore refugees and asylum seekers who came to Australia under Medevac last year and are now being held in hotels.

The men at the Mantra Hotel, and the other 120-odd detainees held at Brisbane’s Kangaroo Point Central Hotel weren’t – and still haven’t been – given anyway to protect themselves against COVID-19.

There’s no room to keep social distance in these establishments. The guards don’t take virus protective measures. And one staff member has tested positive for COVID-19 whilst working at each of the hotels that are now deemed alternative places of detention (APODs).

The majority of the information about the plight of these men – who were brought here for medical assistance and then locked away during a health crisis to be given none – has been making its way out to the public via their mobile phones and internet-capable devices.

And as long-term refugee rights advocate Jane Salmon points out, now Lambie has seen this important victory over the line, it’s time to turn back to the greater campaign that involves seeing the Medevac refugees released into the community, so they can have their freedom after seven long years.