The Racialised Violence of Settler Colonialism: An Interview With Deathscapes’ Joseph Pugliese

Speaking of fake news, the nation of Australia was founded upon it. The British staked their claim over the largest island on the planet under the legal fiction of terra nullius: that there were no occupants of the land prior to their arrival.

Then, just in case anybody noticed there were over 500 Indigenous nations existing upon this continent prior to British takeover, the settler state disseminated the myth of peaceful settlement: the idea that local First Nations people simply vacated large tracts of land for the use of invaders.

To help prop up these founding lies, settler academia propagated what became known as the Great Australian Silence. This involved Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people being written out of the history books for near on 70 years after the federation of the colonies in 1901.

This silence within the white community commenced being torn down by so-called “black armband” historians. Anthropologist W E Stanner initiated this process in a series of 1968 lectures called After the Dreaming.

This was soon followed by historian Henry Reynolds’ 1970 work Why Weren’t We Told?, the title of which became a popular refrain.

The ongoing silence

These days, most people seem to generally accept that this nation was founded upon the attempted genocide and dispossession of First Nations peoples.

The Frontiers Wars, the Indigenous massacres, the Stolen Generations and the missions of the Protection Era are all fairly common knowledge.

But while the silence surrounding the violence of the past may have been lifted, suppression of truth is still very much apparent in Australian society today. And in its current form what it’s now masking is the ongoing racialised violence perpetrated upon First Nations peoples in the present.

This violence includes the large number of deaths in custody, the excessive force applied by police on the streets, the overrepresentation of Aboriginal people within the prison system and the continuing forced removal of First Nations children at highly disproportionate rates.

Race violence in settler states

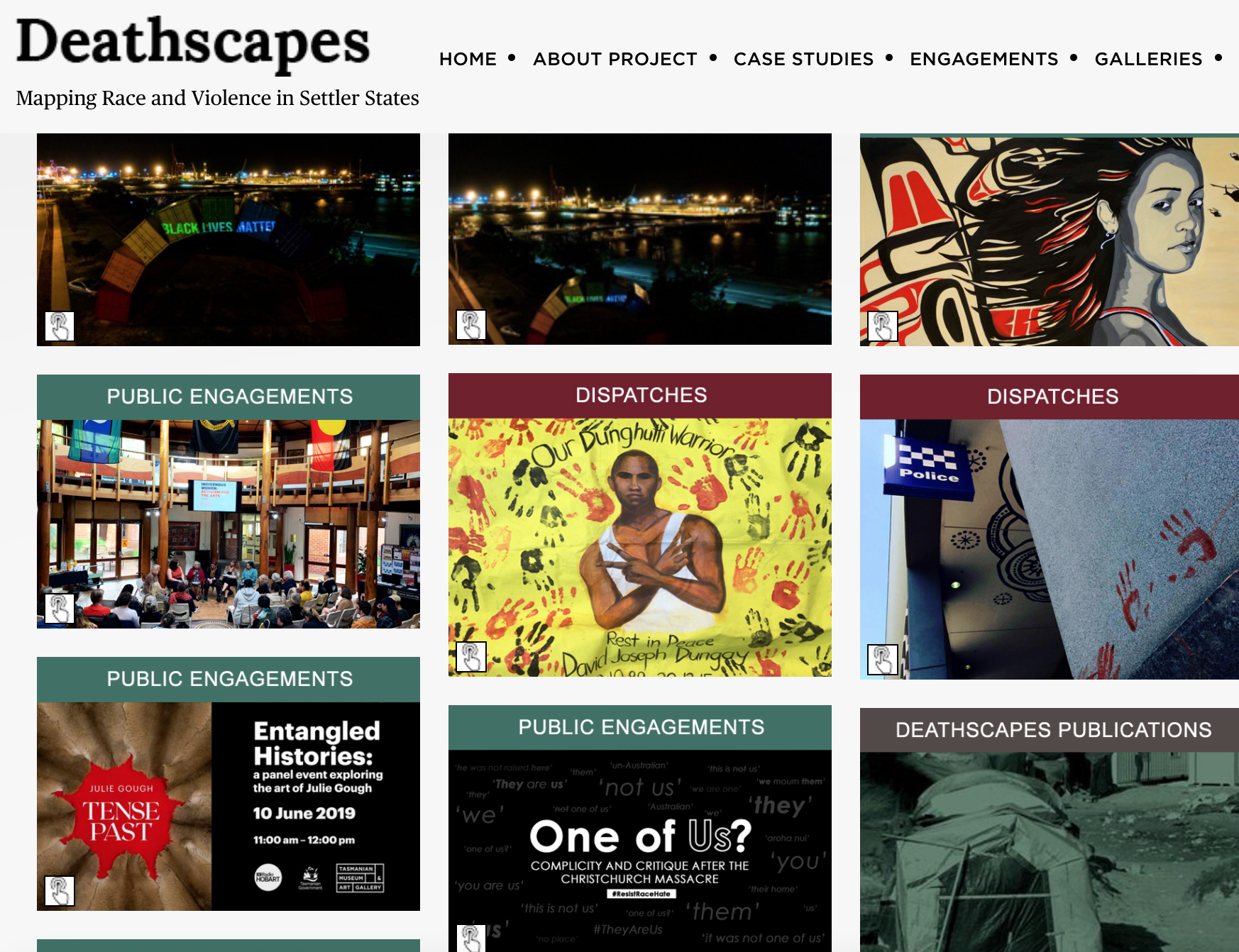

That’s where the Deathscapes project comes in. Over the last four years, Deathscapes has been mapping the racialised and often lethal violence the Australian state continues to perpetrate upon First Nations peoples in the form of custodial deaths and beyond.

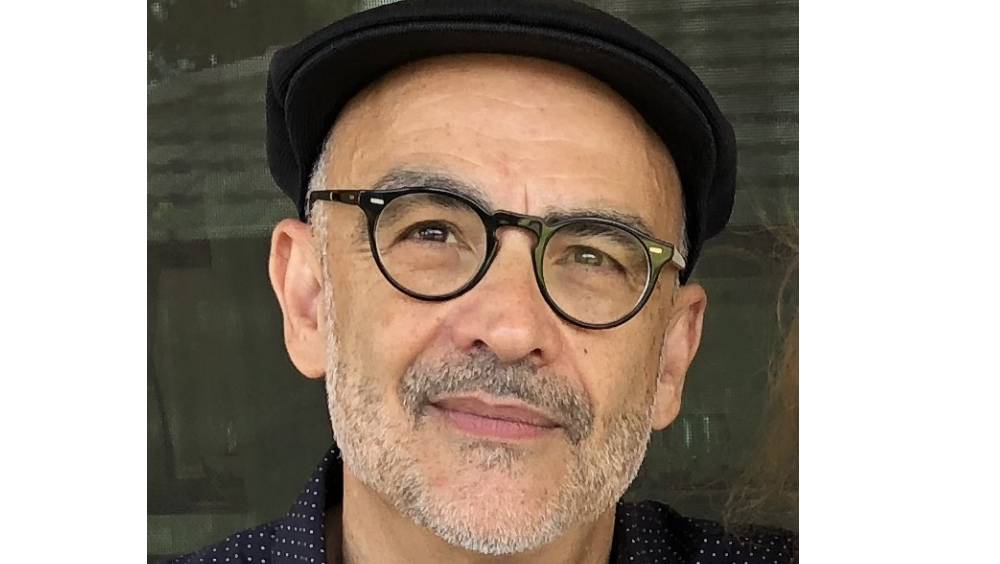

Chief investigators Curtin University Professor Suvendrini Perera and Macquarie University Professor Joseph Pugliese have worked in conjunction with a wide range of local First Nations academics and activists, as well as overseas scholars, to produce a series of case studies tracking this violence.

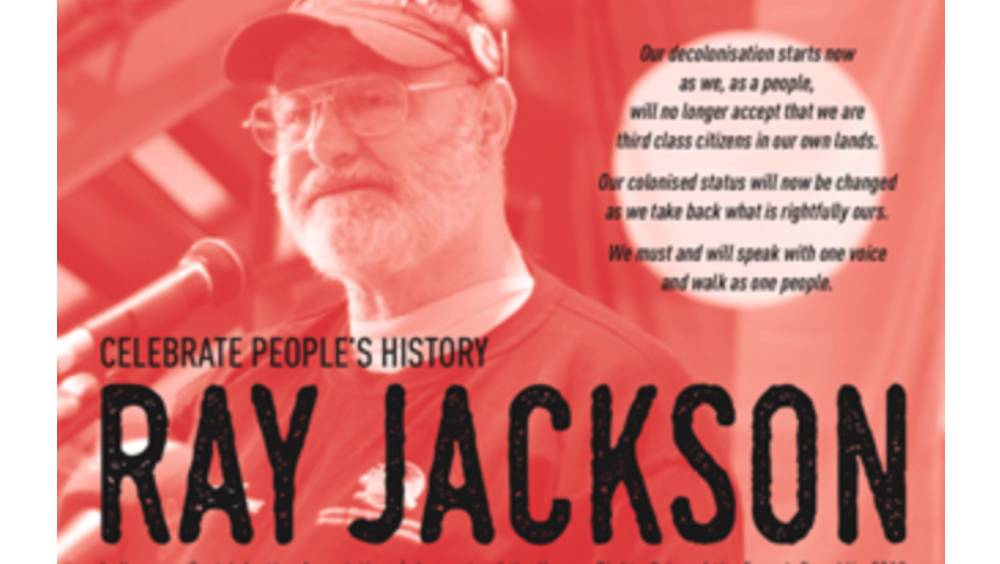

Inspired by the work of Wiradjuri elder the late Ray Jackson, Deathscapes takes this issue a step further by placing the violence of Australian settler colonialism in the context of that occurring in the US and Canada, and it broadens the scope to include brutality towards refugees and migrants.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Professor Joseph Pugliese about racialised violence being an inherent feature of settler colonialism, why it continues into the present, and how structural violence towards First Nations women on the street is also an instrument of the settler state.

Firstly, the Deathscapes project maps racialised custodial deaths in settler colonial states, specifically Australia, the US and Canada.

The focus on Aboriginal deaths in custody in this country has lately been heightened by the Black Lives Matter movement.

There have been over 440 further First Nations custody deaths since the Royal Commission handed down its recommendations in 1991.

Professor Pugliese, how do you explain what’s happening regarding racialised violence and continuing Aboriginal custodial deaths in this country?

One of the key points that Deathscapes makes is that it situates ongoing Indigenous deaths in custody in Australia, Canada and the US, within the lethal framework of the settler state.

Patrick Wolfe’s work on settler colonialism differentiates the notion of colonialism from settler colonialism.

Wolfe says that colonialism moves in, often setting up trading posts, and it’s about mercantile exchange or the kidnapping slaves. But it doesn’t leave a permanent structure that takes over a whole country.

In distinction, settler colonialism moves in and attempts the entire elimination of the Indigenous people. And working on the back of this process of elimination, Wolfe says, you have processes of wholesale replacement.

So, you’ve got Indigenous institutions of law, culture, language, religion and society being demolished and replaced with the settler coloniser’s key institutions.

In one sense, you can’t set up a settler state, Wolfe argues, unless you undertake a process of the elimination of the Indigenous people of the land. That logic really plays out in the three states that we look at.

In the initial periods of settler colonial occupation, in the genocidal campaigns that we know about – the Black Wars – you have government, vigilante groups, settlers and pastoralists going through campaigns of elimination: whether they be systematic executions or the poisoning of water.

Now, down track, you’ve largely taken control of the land, because you’ve eliminated so much of the Indigenous population, even though you haven’t eliminated their resistance.

So, what’s the next step? That is the building up of – what Angela Davis calls – the racialised prison industrial complex, and that becomes an apparatus to continue the process of elimination.

Most chillingly, if you look at the statistics, it’s Indigenous young people and women that get sucked up into that system, and whose lives get destroyed. That becomes another application of the process of elimination.

Importantly, it not only eliminates people from their communities, their cultures and their land, it also breaks continuities of language, transmission of history and culture. So, it has quite a destructive, fragmenting effect.

If you look at how it pans out on the ground, you effectively get lethal processes of destruction happening through the sequestering of Indigenous people in such high numbers.

In terms of their over representation in prison systems, we know that the largest population groups statistically in places, like Australia, are Indigenous people.

You mentioned Angela Davis’ work on the prison industrial complex. She outlines how in the US it grew out of the system of slavery. Can her framework be applied here?

Not exactly in the prison-slavery framework that Davis looks at. But that’s not to say that Australia doesn’t have its own slave history.

It’s important to mark here the University College London’s incredible Legacy to British Slavery site, because there are continuities between all three settler states and their practices of racialised enslavement and elimination.

They track the way that on abolition, the key British investors and traffickers in African slavery in the UK were left with an extraordinary amount of wealth to invest. And a lot of them invested the money in the building of the Australian settler state, and many of them moved here.

There is an inventory on the site of key players who moved to Australia or invested in the building up of key settler institutions.

So, there are really important continuities between the foundations of Australia, abolition and slavery in the US.

We do have our own form of slavery in Australia, in terms the unpaid wages of Indigenous people who were taken as domestic farmhands and domestics within white households in metropolitan cities.

And, of course, we’ve got the whole blackbirding of South Pacific Islanders, as another form of slavery that helped build up the wealth in Queensland, in the sugar plantations and elsewhere.

But if you look at Angela Davis’ work, there’s a key difference in Australia, because we don’t have the big business of continuing slavery in the prison system like they do in the US.

One of the largest population groups of prisoners in the US are African Americans, particularly men. They are employed in exactly slave conditions. Davis argues that it is the continuation of slavery by other forms there.

Aboriginal custodial deaths in Australia take place in the custody of police and corrections. Indigenous deaths in custody are an issue in other settler colonial nations, like Canada.

However, the Deathscapes project takes into account deaths in custody that happen in immigration detention, and it also extends its focus to people of colour, migrants and refugees.

Why does the project take this wider scope? And what does the broader take tell us about settler colonial states?

That’s an important question because, to a degree, it goes to the heart of what Suvendrini Perera and I think is the most innovative aspect of the Deathscapes project.

That is the fact that there was never a formal treaty with Indigenous people in the ceding of their lands in this country. It was a violent takeover.

It was based on the fiction of terra nullius: that there were no civilised occupants. This was the whole premise on which the 1788 invasion took place, as well as the claiming of this country in the name of the British Crown.

Once you’ve got that illegitimate establishment of a settler colonial state, that illegitimacy continues to haunt the state forever after.

This is because you’ve got Aboriginal people with an unbroken refrain saying, “Always was, always will be, Aboriginal land. We have never ceded our sovereignty. We have never formally ceded our lands.”

There are two colliding positions. You’ve got the settler state saying, “We are now a sovereign nation state.” And Aboriginal people are saying, “Well, sorry, you’re actually an illegitimate nation state that has usurped Indigenous sovereignty.”

So, how does an illegitimate settler nation state protect, fortify and try to legitimate its sovereignty? Precisely through the control of its borders, because if you don’t have control of your borders, you don’t have control of your nation state – there is no nation state.

What we began to track is one of the ways in which the illegitimacy of the Australian nation state tries to legitimate itself is through this aggressive, militarised assertion of its sovereignty.

Look at the way in which the whole refugee pushback and the incarceration of refugees is actually called Sovereign Borders. That gives you the linchpin to the whole constellation of factors that we are trying to map here.

We then focused on the violent policies of deterrence and the violent policy of incarceration in violation of UN responsibilities towards refugees and asylum seekers, as well as their outsourcing to these neocolonial outposts: Manus and Nauru.

This all part of that fabric of the assertion of Australian state sovereignty through forms of violence.

Interestingly, people like Uncle Ray Jackson and Uncle Tony Birch – and a number of other key Indigenous activists and scholars that we cite – say, “I’m sorry. You don’t actually have the right to turn away asylum seekers and refugees. That is our right and our call. And we are extending hospitality and welcome to them.”

Uncle Ray Jackson actually held passport ceremonies at the settlement in Redfern, where he extended welcome to refugees and asylum seekers in the name of his Wiradjuri people.

He would often visit detention centres, like Villawood, and sneak in Indigenous passports and offer them to these people, as a way of continuing to assert his Indigenous sovereignty.

Uncle Ray Jackson’s work was so important to us, because he had this very in depth and complex view of how all these factors meshed and how they all pivoted on the implication of sovereignty by the settler state and the ongoing contestation and assertion through various practices by Indigenous people.

Indigenous Femicide and the Killing State is one of the case studies the project carried out. It broadens the scope of custody deaths to the large number of First Nations women in settler colonial states who are killed on the streets, in homes and on the margins.

The study posits that the large numbers of deaths and the associated violence towards Indigenous women are in no way random acts, but rather they’re “a systematic outcome of the logic of settler colonialism”.

Can you outline what this logic pervading these societies is and how does it lead to Indigenous femicide?

The case is co-authored by three brilliant Indigenous scholar-activists: Bronwyn Carlson, Hannah McGlade and Tess Allas. What they argue is that there is a long history of racialised violence against Indigenous women in this country.

The Indigenous femicide that we’re seeing now has got deep roots within the settler state.

If you look at the cases, they map the way in which white men in particular were instrumental in kidnapping Indigenous women and placing them within regimes of sexual and domestic slavery.

There’s the graphic example of the kidnapping of Tasmanian Aboriginal women in the early 19th century and their enslavement by the white sealers on Bass Strait islands. Now, that’s not part of the history that’s too well known in this country and it should be.

We’ve got Julie Gough, a Tasmanian Aboriginal artist, who has listed the names of all of her ancestors and peoples who were kidnapped by white sealers.

The case study tracks the way in which that systemic violence played itself out not just in incarceration of Indigenous women, but in the killing of Indigenous women in civilian sites – in plain sight, so to speak – often without any recrimination or penalty.

We cite some Indigenous women who have been subject to sexual violence. They’ve tried to report the sexual violence and then white police officers scoff and say, “We are sure you brought this upon yourself.”

There are deep racist and sexist attitudes towards Indigenous women coming from the settler state.

But what we saw, which is particularly disturbing, was not only is there an increasing incarceration rate of Indigenous women in this country – and in other settler states like Canada – but these civilian spaces have become spaces other than the nation.

Spaces that you would think ostensibly these women would be protected in – the beach, the park, the street, the road – become sites of unsafety, insecurity and in particular sexual violence. We talk about what happens in the streets and on trains.

If you look at Indigenous scholars and activists, they say Indigenous women are targeted precisely because they represent the future of Indigenous nations. They’re the ones that reproduce the future nations and they’re also the key transmitters of culture and history.

Once you begin to eliminate Indigenous women, that process of elimination has the knock-on effect of destroying culture, society and attachment to land.

So, the logic of elimination has a particular racial and gendered dimension if you look at it in the context of Indigenous femicides.

The Indigenous femicide happening in Canada is quite well documented. However, what’s currently happening in Australia is less reported.

Why is there such a silence around the structural violence perpetrated upon Indigenous women in the Australian setting today?

The great silence that surrounds the attempted genocide of the Indigenous people in this country – and the large indifference of the settler state to these forms of violence – is of benefit to the state.

It sweeps it under the carpet and defaces it, when it’s actually one of the key practices of violence that are unfolding in this country.

It is not just Indigenous women. It’s the ongoing Indigenous deaths in custody. Once the Royal Commission’s 339 recommendations were handed down, what changed? Nothing.

Not one prison officer, correctional guard or police officer has been convicted of an Indigenous death in custody, so everything has remained intact except the ongoing elimination of Indigenous people.

So, why this indifference? Well, it benefits the settler state to pretend that it’s not happening – to not tackle this issue.

You mentioned that one of the inspirations for the project was the work of Wiradjuri elder Ray Jackson.

As the president of the Indigenous Social Justice Association (ISJA) Sydney, Jackson long called out deaths in custody and racialised police violence in this country.

Can you speak a bit more on the significance of Ray Jackson’s work, and how it influenced Deathscapes?

What we particularly admire about Uncle Ray Jackson is that he had quite an internationalist vision of racialised colonial power.

He had an expansive vision, where he tried to connect what was happening in one settler state, Australia, with larger transnational movements. He was always interested in what was happening in the US with Native Americans, and in Canada with Native Canadians.

He felt that we had to create alliances in order to strengthen decolonising and as well, in order to unpack how these structures are not just contingent to one state but they’re actually transnational in their reach, reproducing certain patterns of lethal violence, like ongoing deaths in custody and the overrepresentation of Indigenous people in prison.

That was the aspect that we so admired and inspired us in the case of Uncle Ray Jackson. But, also, he worked full time on Indigenous deaths in custody. He was one of the linchpins in the movement holding families together and pursuing justice in the coronial system.

And he took time to extend his compassion to other people who fell within the violent snares of the settler state, specifically asylum seekers and refugees.

As I said, he did that specifically by initiating the Aboriginal passport movement, offering welcome and going to those detention centres, as a way of asserting unbroken Indigenous sovereignty over country.

As you can see, a lot of what we do in the Deathscapes site is fully inspired by the extraordinary social justice and expansive compassionate vision of Uncle Ray Jackson.

And lastly, Professor Pugliese, after four years of the Deathscapes project, do you see an end to state violence towards racial minorities within these settler colonial states? And what has to happen in order to bring substantial change?

No, I don’t, sadly. We just need to look at the numbers themselves – which embody real lives and individual names – to see things are escalating. The numbers themselves speak to the ongoing escalation. So, I don’t see an end.

But, what changes? Centrally, there has to be an opening up of the foundational question that Indigenous people have brought to the fore time and again.

There has to be an acknowledgement that we’re living in an illegitimate setter colonial nation that has been built on the expropriation of Indigenous land and the usurpation of Indigenous sovereignty.

The Australian state has to enter into dialogue with the various Indigenous nations and begin to discuss with them precisely how to make amends: restitution, reparation and acknowledgment of Indigenous sovereignty over land.

That’s the real truth and reconciliation process that Indigenous people are calling for.

Unless we open that up, everything else will be cosmetic, as we have seen with Indigenous deaths in custody recommendations. They were all very well meaning and important, but hardly any of them have been implemented.

At the David Dungay coronial inquest, I witnessed firsthand that so many of the malpractices that led to his death were the result of not actually having followed the recommendations of the Royal Commission.

Those things are important. But unless we begin to tackle the core issue of negotiating and talking with Indigenous nations and beginning to make amends for the foundational violence of this nation state, the rest will just keep going on – the lethal, racialised dimension will continue.