“There is Greater Need for an Australian Bill of Rights Now, More Than Ever,” Says Wilkie

The second wave of COVID-19 with its accompanying lockdowns is causing widespread confusion throughout the community.

Restrictions on movement, association, and on our ability to continue with our regular lives are leading to questions about whether citizens’ rights are being infringed upon.

Extreme measures to curb the spread of the virus aren’t the only aspect of the current political climate provoking questions around a growing divide between government and the people, which appears to permit ministers and bureaucrats to ride roughshod over the wants of the constituency.

The numerous high-profile whistleblower prosecutions, the AFP press raids on journalists and the increasing crackdowns on critics of government – whether that be individuals or charities – are all leading the public to question our rights to information, opinion and expression.

Unlike all other comparable liberal democracies, the rights of Australian citizens aren’t guaranteed or protected under a national bill or a charter of rights.

So, when we talk about the rights we do have in this country, there are only a very few we can legally fall back on.

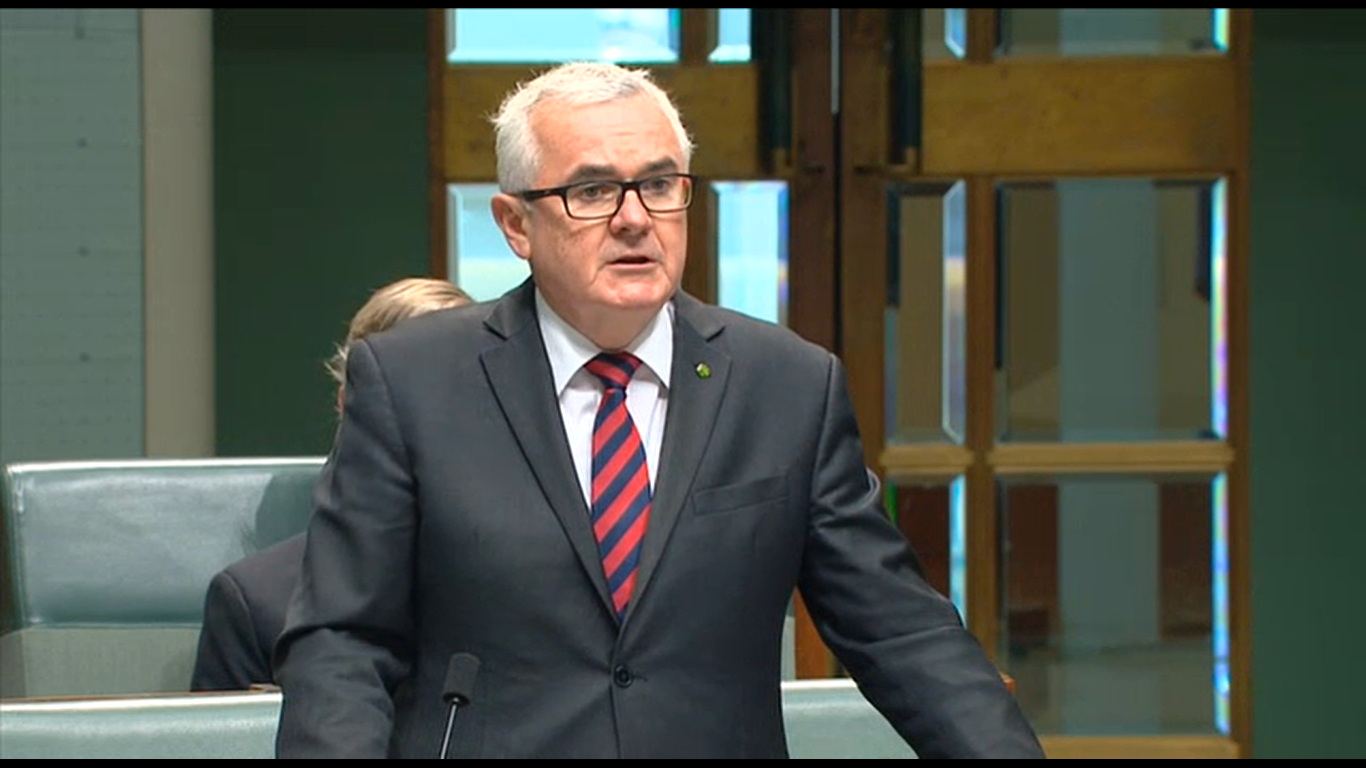

Federal Independent MP Andrew Wilkie has long advocated for a federal bill that “would enshrine the fundamental rights of all Australians” in law. And he maintains that “there is greater need for an Australian bill of rights now, more than ever”.

Clarification amid chaos

“There are so many controversial matters happening,” Wilkie told Sydney Criminal Lawyers. “There are so many questions being asked by all parties about the power of the state, the states and territories – the very nature of our federation.”

“Understandably, that creates questions about what rights we have,” he continued. “What rights do governments have? How far does their power extend? And does it extend too far when whistleblowers are persecuted?”

Wilkie has introduced two rights bills into parliament over recent years. The first in 2017 and then again in 2019. However, the major parties have long been reluctant to consider such legislation, with the presumed reasoning being that it would serve to limit their powers whilst in office.

The federal member for Clark explained that a bill of rights would shed light upon issues such as whether a person has a right to refuse a vaccine, can state governments shut down borders, or whether the federal government has the right to restrict movement between countries.

“I’m not opposing any of those things,” Wilkie made clear. “They’re questions in people’s minds. And if we had a bill of rights, it would bring clarity to exactly what rights individuals, the community and the government have.”

A lack of protection

When the COVID pandemic first hit in March last year, emergency powers were sparked, which permit both federal and state ministers to enact laws via a mechanism known as delegated legislation, which rules out the need for parliamentary oversight.

Many of these public health laws have been straightforward, whereas some have caused controversy. Yet, while citizens can question these laws, it’s difficult to legally challenge whether they infringe upon basic rights, as there are hardly any enshrined in law.

“The bill of rights that I proposed would render invalid any Commonwealth, state or territory law that’s inconsistent with the bill of rights to the extent of that inconsistency,” Wilkie said, adding that currently “there are only five federal acts” protecting rights, which “go to issues of discrimination.”

These are the Human Rights Commission Act 1986 (Cth), the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth), the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth), the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) and the Age Discrimination Act 2004 (Cth).

And while our nation has ratified the seven core international human rights treaties, this means that our government has agreed to uphold the rights within them at the international level, not domestically.

Meanwhile, the US, the UK, Canada, and New Zealand all have legislation enshrining the rights of their citizens.

“There are no protections for a very broad range of fundamental human rights: housing, education, health. There is no act at the federal level that protects those rights,” Wilkie stressed.

“So, we need an act – a bill of rights – that will protect all fundamental human rights. It is as simple as that.”

Curbing encroachments

Since the 2001 9/11 terror attacks, 90-odd pieces of legislation relating to national security and counterterrorism have been passed at the federal level. And commentators have been warning that rather than just impacting terrorists, these laws have gradually eroded the rights of all citizens.

Of late, it’s becoming increasingly apparent that these measures are now being used to target citizens, which has been evidenced with the closed court proceedings against whistleblowers, the silencing of critics via anti-terror processes, as well as the carte blanche on our metadata.

“There is no doubt that some of those pieces of legislation are warranted – many were not – and at least some do infringe on basic human rights,” Wilkie continued. “Where they do infringe on basic human rights, a bill of rights would rein them in.”

“It would limit the scope of those pieces of security legislation, because it would have primacy.”

According to the MP, a bill of rights would also have implications for the “hundreds of additional security reforms” that have been passed at the state and territory level, as well as impact upon such legislation at the drafting and enacting stages.

The rights of the few

During his second reading speech on the Australian Bill of Rights Bill 2019, Wilkie questioned why instead of moving to enshrine the rights of all citizens under a single act, the Morrison government is pushing for the Religious Discrimination Bill (the RD Bill).

A pet project of the PM’s, the RD Bill has been widely derided for proposing to provide those of faith with the right to discriminate against others in the name of their religion.

Wilkie said in parliament that it would “perversely” further restrict human rights, whilst creating special rights for a few.

The first two iterations of the RD Bill were released in 2019. And the proposal was put on hold when the COVID crisis commenced. However, attorney general Michaelia Cash has recently stated that a third draft of the bill will be released by December.

“It does appear that there is a risk that any religious discrimination bill, in the process of giving people more rights, is going to be at the expense of other people’s rights,” Wilkie warned.

“For example, in Tasmania, we have quite good anti-discrimination protections at the moment. And there is a fear down here that the federal government – in attempting to give some people more rights – is going to take away rights that already exist in this state,” he concluded.

“There is a real risk that it’s going to be bad legislation.”