Uprising in West Papua: An Interview With Journalist John Martinkus

The construction of the Trans-Papuan Highway is a mammoth project the Indonesian government has had underway since 2013. The 4,325 kilometre road cuts its way through the mountains of occupied West Papua to join the coastal cities of Sorong and Merauke.

In early December 2018, West Papuan rebels attacked a group of road construction workers in the highlands, killing around 19 of them. And the subsequent months-long crackdown by Indonesian forces in Nduga regency displaced thousands of West Papuan villagers.

On 18 August last year, protests broke out across West Papua, which Jakarta split into two provinces in 2003. Sparked by an incident on the island of Java involving the abuse of Papuan students, the demonstrations were the largest in two decades.

The unrest in West Papua went on for weeks. Jakarta responded by deploying thousands more troops and cutting off the internet. Unarmed protesters were shot and killed. Yet, the calls for a free West Papua continued.

The Act of No Choice

The United Nations handed Indonesia control of West Papua in 1963. This was after it was briefly administered by the UN following the Netherlands having given up its colonial rule.

And part of the handover agreement was that Jakarta allow the Papuan people to hold a vote on self-determination.

So, in 1969, Indonesia handpicked 1,026 West Papuans to partake in the UN brokered Act of Free Choice. And under threat of reprisal from Indonesian troops, all of the selected locals chose to remain an Indonesian colony.

However, the West Papuan people have continued to push for independence ever since. In 2017, around 1.8 million locals – 70 percent of the Indigenous population – signed the West Papuan People’s Petition, which calls for a new internationally supervised independence vote.

From the frontline

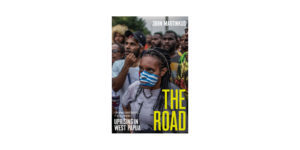

Renowned Australian journalist John Martinkus has just published a new book, The Road: Uprising in West Papua. It tracks the reignited independence movement, as well as the brutal crackdown on the part Indonesian security forces.

Martinkus travelled to West Papua in the early 2000s, where he reported on the operations of the notorious Indonesian special forces group Kopassus, as well as those of the OPM, the Free West Papua Movement.

As the conflict zone reporter puts it in The Road, “when war was mounting in Iraq in 2003, most of my colleagues went there and I ended up in Merauke, Papua. The south-easternmost town in Indonesia. Literally the end of the road”.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Martinkus about the long-term ban on international journalists in West Papua, the significance of last year’s widespread protests, and the resolve within the Papuan people that will never see them give up.

Firstly, you’ve just released your second book on the struggle of the West Papuan people under Indonesian rule. It’s titled The Road, after the Trans-Papua Highway. John, what’s the significance of this road? Why is it a central theme of your book?

It’s the first time the Indonesians have tried to connect a very remote part of the country to the rest of their network.

The road is going through this area that’s very isolated and has hitherto been very much untouched by Western civilisation, apart from missionaries and a few Dutch expeditions back in the 50s.

What it has done is it’s stirred up this passionate rebellion amongst the people there against foreign intrusion. That’s why it’s significant, because it’s stirred up a hornet’s nest.

An incident along this road in December 2018 involving locals attacking non-Indigenous road workers led Indonesian troops to crack down upon villages in the Nduga regency. What has the impact of this military operation been?

The impact has been huge. Around 45,000 people have fled from their homelands. They’ve gone to either neighbouring provinces or they’ve gone all the way across the border into PNG.

That’s massive. We haven’t seen that sort of dislocation of people since the Indonesian operations in the late 70s.

The local people are terrified about the Indonesians coming through. They bring diseases, industries, dispossession of people from their land: all the classic symptoms of a new power moving in.

There’s also militarisation, which really scares the local people. They don’t want the Indonesian troops up there. They’ve managed to live all this time without them.

So, the road is a tremendous problem for the local people.

By August last year, there was a groundswell of pro-independence actions throughout West Papua. These were sparked by an incident in Surabaya, which involved Indonesia troops racially abusing West Papuan students.

You’ve been following the situation in the region for a number of decades now. How significant was this uprising in terms of reigniting pro-independence sentiment?

It was quite remarkable. It broke out at the same time I was in Timor attending the 20th anniversary independence celebrations. And I was watching what was happening in West Papua on Indonesian television.

It was huge, because there has never been such widespread opposition to Indonesian occupation as there was in those days in August.

Basically, every major population centre was uprising. It was a little bit like what’s happening now in the States.

It was reported quite well in the international media, but it wasn’t reported that well in Australia. And the obvious reason for that is that journalists aren’t allowed to go there.

Anne Barker from the ABC managed to get to Sorong for a day or two, but that was about it. Nobody from SBS or any of the papers got up there, because they simply weren’t allowed.

In 2017, huge numbers of West Papuans risked their lives to sign the people’s petition, calling for a new, and this time genuine, vote on independence.

Would you say there was a link between the enthusiasm around the petition and last year’s regionwide pro-independence actions?

Totally. I reported from there in 2002 and 2003. I haven’t been back since, because you’re not allowed.

But, the lingering undercurrent from my experiences was that the people were looking at East Timor and thinking that they had independence, so why can’t West Papua have it. That has just flowed through to the next generation. And that’s why the petition got up.

They sent it abroad and presented it to the UN. It was a long process. They got knocked back the first time they tried. Then they almost had to use subterfuge to get it in again. In the end, it was tabled and it’s on the record.

If you go up there, it’s remarkable because the people know all about the different UN agreements in 61, 62 and then in 69 with the handing over and the Act of Free Choice.

These people can’t read or write, but they know all this history. They know that they’ve been done over and they’re just not going to accept it.

I spoke to United Liberation Movement for West Papua (ULMWP) spokesperson Jacob Rumbiak last month. He said that for West Papuans living in their homelands the threat during the COVID-19 pandemic hadn’t been the virus itself, but rather the Indonesian military.

From what you know, what has the situation been like in West Papua while most of the globe has been in lockdown?

For many years, since 2003, access that foreigners have to those two provinces – Papua and West Papua – has been really limited.

There have been a few tourists go through, but not much. Certainly, no businesses, journalists or human rights organisations.

So, they’re quite isolated. And in 2019, when the violence broke out after the Surabaya incident, the Indonesians did things like cut off the phone network, cut the internet and stop all travel.

Now with COVID, the Indonesians are using that as an excuse to shut down the region further or permanently. The people can’t go anywhere. They can’t call anybody. They can’t do anything.

And lastly, John, you make the case in The Road that the independence movement has been reignited. Is this a pivotal moment? Do you foresee West Papuan people gaining control of their own country once more?

I was in Timor before independence and I could see where that was going. It was obvious that they were not going to stop fighting until something happened.

I got despondent about it for a while. In late 98, I was living there, and the violence was every day. Every now and then, people would get killed. It was just part of daily life.

I saw the same thing happening in Papua. The people will not stop fighting. And the Indonesians will not stop killing them, until there is some kind of resolution.

The only way for the Indonesians to sort this out is to have some kind of a referendum to move ahead, because otherwise the war is just going to keep going.