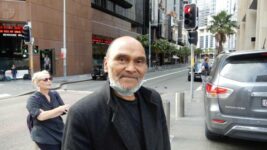

Vale Lanz Priestley: The Mayor of Martin Place

“When you come across a situation and you look and think, somebody should do something about this,” Lanz Priestley once said, “remember, you are somebody.”

And anyone who knew the unofficial Mayor of Martin Place is well aware that he lived by this creed.

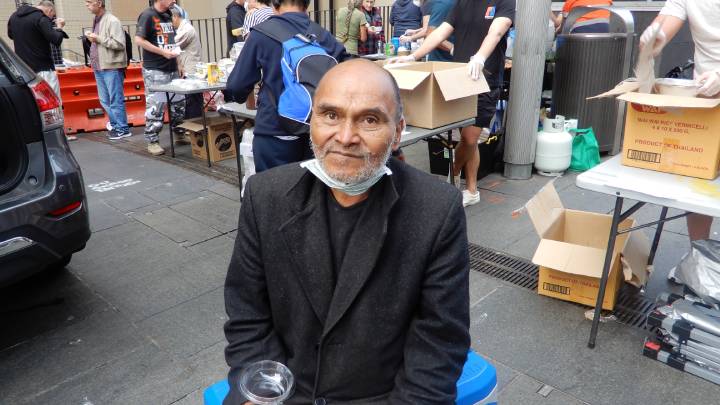

My first encounter with Priestley was in May 2017 when Sydney’s 24-7 Street Kitchen and Safe Space was in full swing in Martin Place. The grassroots setup was located directly under the construction hoarding backing onto the Macquarie Street building opposite the Reserve Bank.

At that time, the CBD initiative was effectively operating as an off-the-grid drop-in centre that fed and sheltered people experiencing homelessness. The kitchen was providing 400 to 500 meals a day free-of-charge, while the safe space had around 50 people sleeping there without fear at night.

As Lanz explained, Martin Place has a long association with homeless people. And in late 2016, as he was putting on a free Sunday homeless dinner, women who were sleeping rough told him that men had been attempting to sexually assault them, so, as the quote goes, he did something about it.

Yet, this was only one of the community-minded initiatives Priestley was the guiding force behind. And while the scope of these projects was remarkable, what was truly astounding was Lanz was overseeing all of them from the side of the road, as he’d had no fixed address since 1991.

A genuine refuge for the homeless

“24-7 took place when he took over the hoarding space. The motivation for that was he found there was an increasing number of homeless women, and they were getting attacked,” said social justice activist Ian Rose. “So, he set up a safe space where they could camp underneath that hoarding.”

According to Rose, “Lanz had been doing these things for a long time. 24-7 wasn’t the first.” And he recalled that Priestley was instrumental in setting up the Just Enough Faith project, which fed around 250 homeless people seven nights a week in the Domain during the late 90s and early 2000s.

“The kitchen was 24/7. So, people could just rock up at any time,” continued Rose, who has been described as one of Lanz’s right-hand-people. “There might be sandwiches from a deli that had been dropped off, or they’d be a meal being cooked, or you could grab a cup of tea and a roll.”

The Martin Place kitchen and safe space began in December 2016. And it was soon renowned throughout the city. People from all over were donating food, clothing, bedding and tents. And celebrities would drop by. But the operation soon drew the ire of the authorities.

As Lanz advised, by May, the City of Sydney homelessness unit had raided it four times. And this led to the boarding up of the sleeping area.

But, as Rose remembers, the cops left the kitchen running, because “over the time it was going, petty crime – such as bag snatching and shoplifting – had dropped in the city by about 30 percent, because people were always able to grab a bite to eat at 24-7”.

However, after NSW premier Gladys Berejiklian publicly stated that the sight of the homeless people made her “completely uncomfortable”, her government passed tailormade laws in August 2017 that forced the Martin Place homeless camp to disband via threat of sending in the NSW police.

“The other real remarkable thing about it was that about 60 percent of the people there were working,” Rose told Sydney Criminal Lawyers. “They would go off to their day jobs and could leave their possessions in the camp area. And they knew that it would be there when they got back.”

Occupying Sydney

“Once Zuccotti Park was occupied, we began our plan to occupy Sydney,” said Larissa Payne, another of Lanz’s co-conspirators. “Within a few weeks, we’d organised Occupy Sydney on stolen Gadigal land, with permission from Elders.”

In coordination with the anti-corporatisation Occupy Wall Street movement, Priestley and Payne organised what became the longest running Occupy demonstration on the globe commencing in October 2011, right here in Sydney’s Martin Place.

“While some would paint Lanz with an anarchist brush – and he was an anarchist indeed – much of his (anti) ideology and refusal to comply with authority he believed illegitimate, came from his Māori worldview,” Payne maintains.

Occupy was utilising the consensus decision-making model, she recalls, which fit in well with the way Lanz’s own community back in Aotearoa came to a decision. Although, when matters called for it, Priestley could always decisively step in.

“The only time Lanz would forgo consensus was in the face of a line of riot cops,” his close friend continued. “That’s when he’d bark orders, always in the interest of community safety.”

Providing dignity to others

Other projects and campaigns that Lanz coordinated included an operation that saw donated furniture moved into the premises of previously homeless people who’d just been housed, as well as Blanket Patrol, The Coffee Brigade, Stop the TPP and Defend the Right to Protest.

Larissa conveys that Priestley had a host of connections globally. And when they were organising pre-Occupy, he’d been able to supply leaked primary documents – “some courtesy of WikiLeaks” – which enhanced his ability to campaign around issues, like the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

But perhaps the most miraculous initiative was Dignity Water, which saw Priestley in mid-2019 organising truckloads of water out to the drought-stricken towns along the Barwon-Darling river system in north western NSW, at a time when the state government was failing these communities.

“Last week, we ended up sending a B-double load of water up there. It was 32,000 litres,” he explained in March 2019. “The towns are absolutely ecstatic. They can actually have a drink without any side effects.”

“We thought, nobody is actually furnishing enough to supply whole towns, so we built up the necessary partnerships in logistics and supply,” Priestley explained.

Rose outlined that the first delivery involved four pallets of water “out to Wilcannia”. Lanz had organised the money for two, whilst First Nations group FIRE organised the rest. From there, the next truckload consisted of 8 pallets, then 32, until it eventually got to 44 pallets of water per truck.

And it must be remembered that this was all being coordinated from the streets.

The saint of Martin Place

On Tuesday this week, word rang out across Sydney that Lanz Priestley passed away last weekend. Social media pages were awash with posts remembering the “thoughtful, selfless being”, whom many admired and indeed, he’d inspired.

“Lanz was a remarkable coordinator. Whatever the world threw at him, he’d roll with it,” declared Rose. “He had an incredible mind. He was one of the most lateral thinkers that I have met in my life or have even read about. His ability to snatch victory out of the jaws of defeat was remarkable.”

Priestley operated outside the sanctioned system. He showed that to exist on the margins does not render one powerless or condemn them to act without humanity. In fact, Lanz proved with grace that when the motivation is the greater good, one can act more effectively than any government.

“As radical and visionary as Lanz was, he was a relentless pragmatist and realist, working with anyone to achieve his goals of community-led decision-making and freedom,” Larissa concluded.

“Lanz always taught me that nothing lasts forever – things grow, cement their place in history, disband, and are reborn.”