Victoria Decriminalises Public Drunkenness

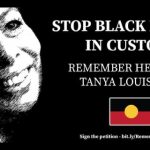

Three years after the death of Yorta Yorta woman, Tanya Day, who was arrested for public drunkenness and suffered a fatal fall in a police cell at Castlemaine Police Station, Victoria has finally passed legislation to decriminalise public drunkenness.

The family of Tanya Day has campaigned tirelessly to reform the law, which has disproportionately affected Indigenous Australians over decades.

Decriminalising public drunkenness was in fact, one of the recommendations of the Royal Commission into Indigenous Deaths in Custody 30 years ago.

A health issue, not a crime

The new Victorian law will come into effect at the end of next year and will treat public drunkenness as a public health issue, not a crime.

Despite the fact that this is seen as an important step towards justice for Indigenous Australians, there are still calls for the Victorian Government to consider wider reform including an agenda which brings greater accountability to policing.

Coroner’s findings

At the end of the Coronial Inquest into Tanya Day’s death last year, Coroner Caitlin English referred the case to the Victorian Department of Public Prosecutions to determine whether criminal negligence had occurred, after considering the evidence surrounding Tanya Day’s death.

After falling asleep on a train, Ms Day was arrested and placed in a cell where she fell and hit her head multiple times within the first hour of being detained. Police left her lying on the floor for another three hours before noticing a lump on her head. She was eventually taken to hospital where she died several days later.

The Coroner’s Report determined that Ms Day was “not treated with dignity and humanity” in accordance with the Victorian charter of human rights. It also noted that “If the required physical checks had been conducted every 20 minutes or every 30 minutes … it may well be that Ms Day’s deterioration was detected earlier.”

The Coroner also found that the police officers who took Ms Day off the train and arrested her for public drunkenness treated her differently than they did another, non-Indigenous, severely intoxicated woman later that same day, who was driven home by police and not arrested or even fined for being drunk in public.

However, the Coroner also said that: “I am not of the view there is evidence to make a finding the differential treatment was due to Ms Day’s Aboriginality.”

Accountability for Indigenous deaths in custody

After conducting its own assessment of Ms Day’s case, last year the Director of Public Prosecutions stated that it would not be pressing charges against the two officers involved.

Despite the numerous Aboriginal deaths in custody that have occurred – and continue to occur – in this country, there has never been a single police officer or prison guard convicted of an offence related to such a fatality.

Subtle change may be occurring however. A prison officer has recently been charged with manslaughter following the fatal shooting of Dwayne Johnstone, a Wiradjuri man, who was handcuffed and shackled when he was shot dead at Lismore base hospital on 15 March 2019.

The case is due in court in March.

Family to sue the Victorian Government

Ms Day’s family has since decided to sue the Victorian government for the false imprisonment of Tanya Day and for wrongfully causing her death.

In a Supreme Court writ filed last December, the lawsuit alleges the state government and police are liable because they unlawfully detained Ms Day, failed to exercise due care when she was under arrest, and by their negligence caused her death.

The suit also alleges that Ms Day’s status as an Aboriginal woman was inextricably linked to her mistreatment by police, and that the state government was aware of the impact this has in carrying out policing.

Queensland is the only state yet to repeal the law

The only State in Australia yet to repeal the law is Queensland.

In Queensland, the offence of public drunkenness is outlined in section 6 of the Summary Offences Act 2005, which outlined the Offence of Public Nuisance, which states:

“A person must not commit a public nuisance offence.

A person commits a public nuisance offence if —

the person behaves in a disorderly way, an offensive way, a threatening way, a violent way, and

the person’s behaviour interferes, or is likely to interfere, with the peaceful passage through, or enjoyment of, a public place by a member of the public.”

The maximum penalty is 25 penalty units ( currently $3,325.00 in Queensland) and/or 6 months imprisonment.

Power to detain and transport intoxicated persons

Queensland police are empowered to detain and transport intoxicated persons to a sober safe centre if they believe the person is causing a nuisance or posing a risk of harm to themselves or another person.

Sober safe centre

If a person is detained because they are intoxicated, police must inform the person that:

- They are being detained and transported to place of safety,

- They will be assessed by a healthcare professional before being admitted to the centre, and

- Intoxicated persons who are admitted to a centre may be detained for up to eight hours, their belongings may be searched, seized and kept in safe custody while they are at the centre and they will be required to pay a cost for use of the centre.

Intoxicated persons may be released from the safe centre if the staff consider they are no longer intoxicated, or if a responsible person takes them to a place of safety.

Place of safety

Queensland police are further empowered to take an intoxicated person to a place of safety other than police custody to recover from the effects of their intoxication, if they think it is more appropriate to do so. A place of safety may be a hospital, if medical treatment is required. It may also be a sobering up shelter or the person’s home or the home of a friend or family member.

However, the police may not release intoxicated persons into a place of safety if they believe that:

- A person at the place of safety is unable to provide care for the intoxicated person;

- The intoxicated person’s behaviour may pose a risk of harm to other persons.

- If the intoxicated person is released to a place of safety other than their own home, the person in charge of the place of safety must sign an undertaking to provide care for them. The intoxicated person cannot be compelled to remain at the place of safety.