Victoria to Decriminalise Public Drunkenness

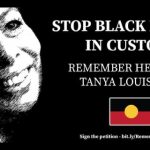

The Victorian government has announced it will decriminalise public drunkenness, just days before the CoroniaI Inquest into the death of Indigenous woman Tanya Day.

The death of Tanya Day

The 55-year old Yorta Yorta woman caught a train from Echuca to Melbourne on 5 December 2017 to see her family.

She was heavily intoxicated and fell asleep during the trip, with her legs said to be blocking the aisle.

As the train pulled in to Castlemaine station, the conductor called police to request help with an “unruly” passenger who he said could not find her ticket.

Police arrived at 3.10pm and shook Ms Day awake. They then arrested her for being drunk in public and and took her to the police station.

Shortly after 8pm, when Ms Day was scheduled for release after the prescribed four-hours of sobering up, officers at the station realised something was wrong.

The conveyed her to Bendigo hospital, where it was discovered she had bleeding from her brain due to a traumatic brain injury sustained nearly five hours beforehand, when she had fallen in the cell unnoticed. She was not being monitored at the time.

Ms Day later died in Melbourne’s St Vincent’s hospital.

Current legislation

Section 13 of the Summary Offences Act 1966 (VIC) makes it a criminal offence and prescribes a maximum penalty of 8 penalty units (which is $1,289.52 in Victoria) for “any person found drunk in a public place”. Under section 3 of the Act, this includes footways, train stations, parks and school.

A person is deemed to be “drunk” if an ordinary person would consider them to be, which according to the law can be determined through a speech, coordination and/or other behaviour.

Other jurisdictions

Victoria and Queensland are currently the only states or territories Australia where being drunk in public is still considered a crime.

Recommendation 79 of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody states, “in jurisdictions where drunkenness has not been decriminalised, governments should legislate to abolish the offence of public drunkenness”.

The following recommendation sets out that laws against public drunkenness should be replaced by the introduction “non-custodial facilities for the care and treatment of intoxicated persons”.

Victorian reforms

Victorian Attorney-General, Jull Hennessy, has recognised that Indigenous people are most vulnerable to being targeted by public drunkenness laws, foreshadowing the replacement of these laws by a health-based regime.

“The Andrews-Labor Government acknowledges the disproportionate impact the current laws have had on Aboriginal people and pay tribute to the community members who have advocated for this change,” Ms Hennessy stated.

“It’s nearly 30 years since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, so I certainly agree with all of the sentiments that this can’t come soon enough.”

The law in NSW

While there is no crime of public drunkenness in NSW, the section 206 of the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (LEPRA) provides that:

- A police officermay detain an intoxicated person found in a public place who is:

- behaving in a disorderly manner or in a manner likely to cause injury to the person or another person or damage to property, or

- in need of physical protection because the person is intoxicated.

Any such detention is regulated under section 207, which requires, among other things, that the person cannot be under 18, must be kept separate from others where possible and released when they cease to be intoxicated.

The death of Rebecca Maher

Indigenous woman Rebecca Maher died in Maitland police station in 2016 after being placed in protective custody under the LEPRA.

She was not permitted to nominate a responsible person for her to contact, which is a requirement under the law.

New South Wales Coroner, Therese O’Sullivan, found that Ms Maher’s death could have been prevented if police had better monitored her while she was in custody, or called an ambulance when she repeatedly complained to them about being in pain.

Ms O’Sullivan ultimately found that Ms Maher “should not have been kept in police detention”, and that the police failure to comply with their policies to monitor arrested persons and call for medical assistance when asked to do so breach their policies and contributed to the woman’s death.

“There seemed to be a consensus among various officers that the power to detain an intoxicated person was to be exercised to allow [the person] to sleep off,” the Coroner stated, adding “I am troubled by this attitude.”