Victorian Government Backtracks on Promise to Decriminalise Public Intoxication

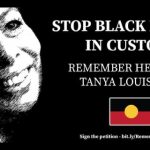

The government headed by Daniel Andrews in Victoria promised to decriminalise the crime of public intoxication following the tragic death of Yorta Yorta woman Tanya Day in 2017, but now says the offence won’t be repealed until at least next year.

The decision is disappointing to the family of Ms Day, which has been campaigning for the abolition of public drunkenness laws since she died after hitting her head on the concrete floor of a police cell.

The preventable death of Tanya Day

Tanya Day’s story, like that of so many Indigenous deaths in custody, has led to frustrations and raised questions amongst the wider community.

What we do know is evidence presented at the Coronial Inquest into Ms Day’s death, which heard that she boarded a train from Echuca train station in northern Victoria with a ticket to Melbourne, but never made it to her destination.

At some point during her journey, Ms Day was approached by a ticket inspector who testified that she was lying with her feet blocking the aisle, although other passengers have disputed this, saying they did not witness anything abnormal.

The ticket inspector called the police. Ms Day was taken off the train, arrested by police for being drunk in a public place, and taken to Castlemaine police station where she was detained in a police cell.

Despite the requirement under police guidelines that Ms Day be physically checked every 30 minutes, Ms Day was left alone, and unattended for several hours.

The CCTV footage shows that at around 5:00pm Ms Day fell and hit her head on a concrete wall of the police cell. When a physical check up of Ms Day was done three hours later, police noticed the bruise on her forehead.

An ambulance was called, which took her to Bendigo hospital. A scan revealed a massive brain hemorrhage and she was flown by helicopter to St Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne, where she underwent emergency surgery. Ms Day died in hospital seventeen days later.

Coroner recommends abolition

In her final report, Deputy State Coroner, Caitlin English, made a recommendation that the Victorian Government abolish the offence of public drunkenness.

It is a criminal offence which disproportionately impacts some of society’s most vulnerable people, including those who are indigenous, homeless and mentally ill.

Coroner English also noted that, “Ms Day’s death was clearly preventable had she not been arrested and taken into custody”.

She further outlined that “an indictable offence may have been committed” and recommended the DPP consider charges against the police officers who had a ‘duty of care’ to Ms Day while she was in custody.

The Victorian coroner based these conclusions on evidence that revealed the officers on duty had failed to carry out proper cell checks in relation to a woman who was clearly in distress. This left Ms Day’s condition to deteriorate, when it could have been treated at an earlier stage.

Despite this, no charges have ever been laid against the officers involved.

And now the Victorian Government has pulled back its commitment to decriminalise public drunkenness until November 2023, despite promising to do so last year.

Why the delay?

The government’s official announcement was mooted earlier this year by statements from Premier Daniel Andrews which suggested that the pandemic had placed pressures on the health system and caused a delay in establishing trial ‘sobering-up’ centres.

The Victorian Government has committed some $20 million plus in funding to the centres, which will coordinate a public health and police-led response, but with the aim of diverting offenders away from the criminal justice system and into the health sector.

However, many believe that the real issue behind the delay of reform has less to do with Covid-19 related issues and more to do with a stand-off between Victoria’s powerful police union and the Victorian Government.

The Police Association of Victoria has pushed back against decriminalisation, saying that the Government has “failed to deliver clarity to the community about the way that the reform will be implemented and how the community will be protected from alcohol-fuelled offending”.

According to Victoria’s crime statistics, there were 2,984 drunk and disorderly offences recorded last year, but the numbers only tell part of the story, often those arrested are indigenous – and given that many indigenous Australians have underlying health issues, there do need to be safety nets in place – including having medical intervention immediately available – so that lives are not put at risk.

In New South Wales, public drunkenness” was officially decriminalised in the late 1970s. Queensland is the only other state (along with Victoria) which continues to make being drunk in public a criminal offence.