Victorian Liberals Push for Harmful Anti-Sex Work Laws

The Victorian Liberal Party recently passed a motion to support the Nordic model of sex work regulation. This is a sex work policy that criminalises clients and support structures of sex workers, rather than the workers themselves.

Passed at the April Liberal State Council meeting, the motion outlines that “a more sensible policing policy” will “protect vulnerable women,” as well as drive down demand for sex work and reduce people trafficking.

However, sex worker advocates state that rather than protecting sex workers, the Nordic model actually increases their risk of violence, undermines their human rights and threatens their health and safety.

And with the state election set for November, Victorian sex workers have grave concerns that a conservative win could lead to the enactment of these regressive laws that will further criminalise their industry and force them to work under dangerous conditions.

Driving sex work underground

“The Nordic model criminalises not just clients but also third-parties,” explained Jane Green, spokesperson for peer only sex worker organisation Vixen Collective. This includes brothel owners, managers and security, “as well as those perceived to be living off the earnings of sex work.”

“In reality the application of these laws has meant that sex workers working together in small groups, or even in pairs have been prosecuted,” Ms Green continued. She added that landlords can even be charged, which has led to sex workers being evicted and experiencing homelessness.

According to Green, police engage in the “intensive surveillance of sex workers” in order to locate clients to arrest, which causes sex workers to employ “police avoidance strategies,” which lessens their ability to use safety mechanisms, such as screening clients, due to client fear of arrest.

“Having to avoid the police means that sex workers are often working in isolation, away from support structures and less likely to access police assistance for fear of coming to police attention,” Ms Green told Sydney Criminal Lawyers®.

And she stresses that there’s absolutely no evidence that these laws reduce the number of sex workers or reduce trafficking, which are the effects those who support laws like these claim they are intended to have.

Intentionally increasing harms

Sweden was the first country to pass laws that criminalised the buying of sex back in 1999. Similar versions of these laws – which are now known as the Nordic or the Swedish model – have since been adopted by Norway, Iceland, Canada and Northern Ireland.

France adopted the laws in 2016, with the stated aim of protecting sex workers, who had previously been directly targeted by laws that criminalised public soliciting. But, a recent study of the French laws reveals that the criminalisation of clients has been more detrimental than the original laws.

Researchers found that 42 percent of sex workers are now more exposed to violence, 70 percent observe no improvement or a deterioration in their relations with police, 78 percent report having lost income and 63 percent have experienced a deterioration in living conditions.

And as Ms Green points out “for some supporters of the laws, these harms are intended.” Anne Martin, head of Sweden’s trafficking unit, has said “of course the law has negative consequences for women in prostitution, but that’s also some of the effect that we want to achieve with the law.”

Partial criminalisation

Currently, the Victorian sex industry operates under a licensing model, which is regulated via the Sex Work Act 1994 and the Sex Work Regulations 2016. The registration and licensing of sex workers, managers and industry businesses is administered by Consumer Affairs Victoria.

Ms Green makes clear that this system is far from adequate. “Under licensing, street-based sex work has remained criminalised and any sex work that is noncompliant with the rules laid out by the legislation is also criminalised.”

The “two-tiered” system that licensing creates undermines the health and safety of sex workers, “because sex workers in the noncompliant part of the sex industry are less accessible to health, outreach and sex worker organisations.”

Another detrimental aspect of the licensing system is that “sex workers are placed in an oppositional role from police,” Green explained. This is because those working in the illegal part of the industry “often fear coming to police attention.”

But, she added that it is also because “police do not relate to sex workers as they do to other members of the public, because sex workers are not treated as other members of the public under law.”

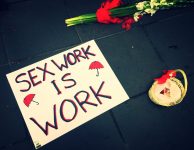

Sex work is work

The Vixen Collective is advocating for the decriminalisation of the Victorian sex work industry, which is the model that has been adopted in NSW. In 1995, the enactment of the Disorderly Houses Amendment Act decriminalised most aspects of the sex work industry in this state.

The decriminalisation model, which was also adopted nationwide in New Zealand in 2003, has been shown to reduce police corruption, improve the health and well-being of sex workers and increase their ability to organise.

Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, UNAIDS and the World Health Organisation all support the decriminalisation of sex work, as a way of protecting against human rights violations and reducing the harms associated with sex work.

And while the decriminalisation of the sex industry has brought these protections for workers in NSW, the Victorian system is failing.

“Sex workers’ rights are infringed upon because the licensing system treats us as intrinsically different from other workers,” Ms Green stated. “And while all work is different, recognising that all workers have rights should be universal.”

The usual lack of consultation

But, rather than consulting Victorian sex workers and their peer-based organisations before creating policy that affects them, the Liberals have decided to adopt an approach to sex work that is guaranteed to further endanger their lives.

“This failure to consult with sex workers isn’t isolated, it’s representative of a broader failure by government to engage effectively with marginalised communities,” Ms Green said and added that policy shouldn’t be formed without “evidence or consultation with the affected community.”

“We’ll be looking to discuss this with the Victorian Liberals and we’d expect them to be open to having that discussion. If they’re not it will represent an even more profound failure,” she concluded.