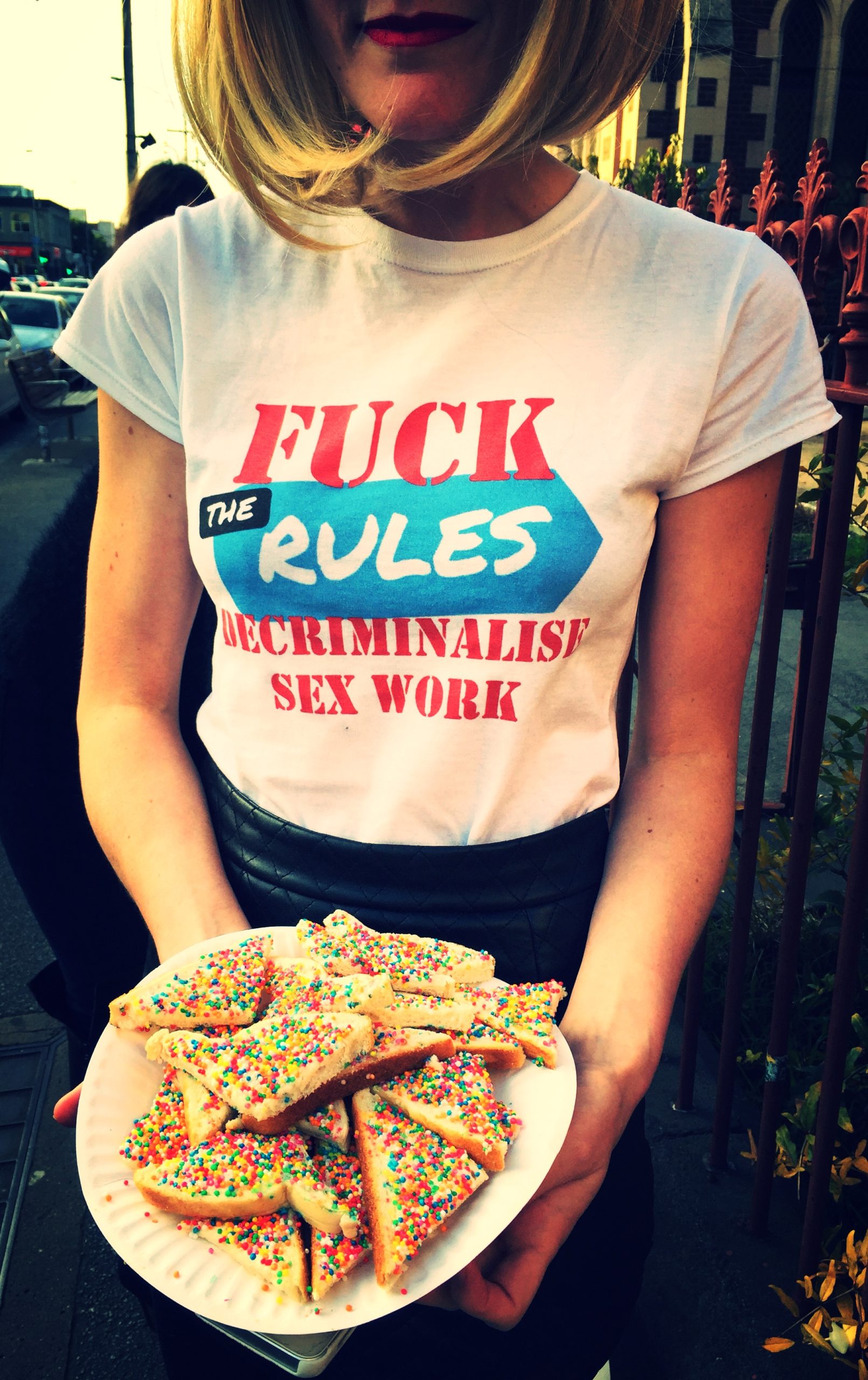

Victorian Sex Workers Demand “Full” Decriminalisation

Sex work is work, no matter which way you look at it. Workers in the sex industry get paid for providing a service. And yet, they’re not afforded the same rights and protections as other workers. Indeed, in many cases, they’re criminalised, which places them at significant risk.

In acknowledgement of this denial of citizens’ human rights, the Victorian government has launched an inquiry into decriminalising the sex industry, as the current two-tiered state licensing model leaves many sex workers classed as criminals, which leads to poor health and safety outcomes.

A sign that the Andrew’s government inquiry is likely to have an impact is that Reason MLC Fiona Patten is leading it. Her previous work led to the establishment of the safe injecting room and assisted dying laws, while as leader of the Sex Party she fought tirelessly for sex industry reforms.

But, while those working within the sex industry right now welcome the long fought for inquiry, they stress the Victorian model must provide “full decriminalisation”, as systems that have been operating in two other jurisdictions for some time now, leave room for improvement.

A peer-led initiative

“Victorian sex workers have been calling for the full decriminalisation of our work for a very long time,” explained Jane Green, spokesperson for peer only sex worker organisation Vixen Collective. And she adds organisations like hers have long been mobilising to get this on the public agenda.

“At present, Vixen Collective works with a number of these local groups,” she told Sydney Criminal Lawyers, “including Class Whorefare, Feminist Insurgency, the local chapter of the sex worker art collective Debby Doesn’t Do It For Free, as well as others.”

And it was Vixen that got the Victorian Labor Party to add sex work decriminalisation to its May 2018 policy platform. Since then, the collective has been pushing for action on this policy that holds “tremendous possibilities”, but could also put the sex worker community at “significant risk”.

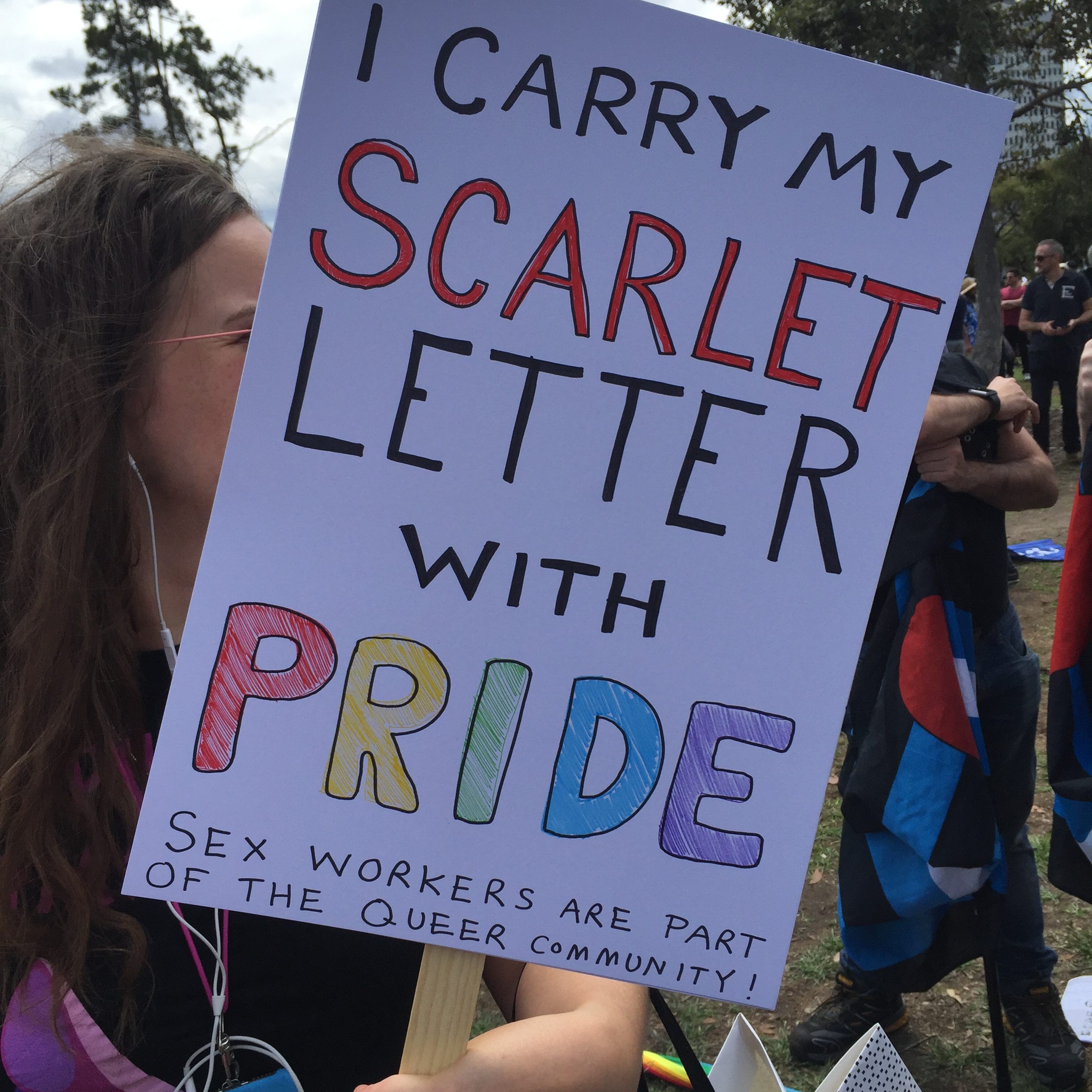

The lived experiences of sex workers reveal that full decriminalisation is necessary, and this is backed by evidence from leading health and human rights bodies globally. However, the inquiry will provide a very public platform for those opposed to sex worker interests and rights to voice that opposition.

“Let’s be clear, bosses and workers in any industry have different interests,” Green stressed. “But, in Victoria, we remain the only state or territory in Australia that does not have a government-funded peer service for our community.” So, well-funded forces opposing reforms will have an advantage.

A growing and reforming trend

If Ms Patten does what she does best, Victoria should become the fourth jurisdiction in the world to decriminalise sex work. The Northern Territory decriminalised just last month, while NSW led the way back in 1995, which was followed by the entire nation of NZ passing decrim laws in 2003.

However, Ms Green points out that there’s an issue in NSW around “the management of street-based sex work”. While she emphasises that the NZ model has “significant flaws”, which include, but are not limited to, “the criminalisation of migrant sex workers”.

“Throwing some people under the bus – the most marginalised and most stigmatised – with the idea you can fix it later, clearly doesn’t work,” said NZ sex worker Natasha. “Now that I live in Victoria, I don’t want to see the same thing happen again.”

“I can’t imagine looking other sex workers in the eye,” she added, “knowing that I’ve got more rights suddenly and they’ve been left behind.”

But, Ms Green also makes clear that despite the fact that the systems operating in NSW and New Zealand needing further reforms, they’ve “immeasurably improved the lives of many sex workers”.

Decriminalisation has been shown to promote the health and well-being of workers, provide them with better and safer working conditions, and it increases access to outreach services, including peer-based health promotion and peer-education.

And another essential outcome of the removal of criminal sanctions around sex work is that workers themselves are able to approach police with complaints or requests for help without fear of reprisal.

Long called for best practice

As Green puts it, when the Victorian sex industry licensing system was brought in “the focus was on controlling and monitoring sex workers”. The Sex Work Act 1994 (VIC) even states this. And there was no real consideration given to the rights, health or safety of workers.

The inquiry by Marcia Neave that preceded the laws we have now, had recommended the decriminalisation of sex work,” the Vixen Collective rights activist recalled. “So now, 33 years after the Prostitution Regulation Act 1986, we’re back to having another inquiry.”

What full decriminalisation would mean, she continued, is that sex workers would have “the same rights as any other workers and workplaces”. Indeed, sex workers simply want the same laws that apply to other forms of work, with nothing special or different.

“That sounds pretty reasonable to me,” Green added.

Continuing the struggle from St-Nizier

The history of sex work is one fraught with criminalisation and corrupting licensing regulations, Jane sets out. She underscores that those regulating systems bring their own forms of discrimination. And she said as things progress in Victoria, they’ll be pushing for past convictions to be erased as well.

The global sex worker rights movement began on 2 June 1975, when hundreds of French sex workers occupied the St Nizier Church in Lyon, demanding an end to police harassment, a system of fines, and the proposed enactment of new laws that could have led to imprisonment.

“It’s critical in this process that the focus is the labour rights, health and safety of sex workers – just like the labour rights, health and safety of workers would be central in an inquiry into any other type of work,” Ms Green concluded.

“If this becomes an inquiry about morality or politics, then that’s a problem.”