What is the Time Limit for Commencing Defamation Proceedings?

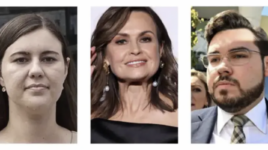

The mainstream media is starting to salivate over the legal strategies Network Ten and News Corp, as well as reporters Lisa Wilkinson and Samantha Maiden, intend to use with a view to defending a defamation case launched by Bruce Lehrmann, the man for formerly accused of sexually assaulting Brittany Higgins in parliament house, Canberra.

However, legal analysts say the case may not be allowed to proceed.

Both of the networks are challenging the delay by Mr Lehrmann in launching his defamation case which, under the law, is generally subject to a limitation period (sometimes referred to as a ‘statute of limitations) of 12 months from the time of publication.

Limitation period

Section 14B of the Limitation Act 1969 (NSW) provides that ‘an action on a cause of action for defamation is not maintainable if brought after the end of a limitation period of 1 year running from the date of the publication of the matter complained of.’

Clauses in other states and territories across Australia contain the same provision.

Mr Lehrmann’s case is well outside the general time limit, with the articles published in early 2021.

However, section 56A(2) allows a court to extend the time limit to up to 3 years from the date of publication, ‘if satisfied that it was not reasonable in the circumstances for the plaintiff to have commenced an action in relation to the matter complained of within 1 year from the date of the publication’.

Mr Lehrmann is arguing for an extension, saying he was delayed in filing proceedings because of the high-profile criminal case against him and prior legal advice, along with mental health issues.

The timeline

Brittany Higgins’ allegations of sexual assault surfaced in early 2021.

In February 2021, Brittany Higgins’ sat for a media interview with Lisa Wilkinson, which went to air on Network Ten. It did not mention Mr Lehrmann. His name was not made public until some time later.

He was charged in August 2021 with one count of sexual intercourse without consent, also known as sexual assault, which carries a maximum penalty of 12 years’ imprisonment.

He has always maintained his innocence.

The trial was due to begin in June 2022 but was vacated and relisted after remarks made by Lisa Wilkinson in her Logies Award speech which were highly-prejudicial to the defendant a well as in clear violation of the judge’s directions not to make such comments. The speech was viewed by millions.

The trial eventually proceeded in October 2022, and ended in a mistrial, as a result of a juror engaging in misconduct by bringing research papers on sexual assault, again in clear violation of the judge’s directions.

Proceedings discontinued

The Department of Public Prosecutions (DPP) decided not to proceed with a second trial of Bruce Lehrmann, citing, amongst other issues, the stress on all parties involved as a result of delayed proceedings and p[rolonged, intense media scrutiny.

The charge against Mr Lehrmann was dropped and he filed the defamation lawsuit shortly afterwards. Around the same time, allegations surfaced from the Office of the DPP that police pressured the ACT’s Director of Public Prosecutions, Shane Drumgold SC, not to pursue a second trial of Mr Lehrmann.

That inquiry is expected to deliver its final report by the middle of this year.

In the meantime, despite all the havoc created by relentless media coverage, it shows no signs of abating. Mr Lehrmann and Ms Higgins continue to make the headlines, with the stories focusing this time on exactly what the media networks will bring to court as evidence to defend themselves against defamation claims.

As a recent headline in the Australian quipped: ‘The Lehrmann Defamation case shapes up to be a defacto rape trial.’ Many media stories in recent days have focused on court documents which include an email, referred to as part of Ten‘s defence to defamation proceeding, included a series of questions sent to an email address believed to be controlled by Mr Lehrmann including “Did you rape Brittany Higgins as alleged?” and offered him a chance to tell his side of the story.

It’s important to remember in amongst all the sensationalist reporting that will undoubtedly continue to follow the proceedings – this case is not about sexual assault, it is about defamation.

What is defamation?

Defamation laws are virtually the same in each state and territory across Australia, and they are very similar to the national laws.

Defamation is defined in the Defamation Act 1995 (NSW), where published material or information:

- Was published, meaning communicated in any way to at least one other person other than the person who was allegedly defamed,

- Identified the person allegedly defamed, whether directly or indirectly, and

Had a defamatory meaning, meaning it was likely to:

- cause the person to be shunned, shamed or avoided by others,

- adversely affect the reputation of the person in the minds of right-thinking members of society, or

- damage the person’s professional reputation by suggesting a lack of qualifications, skills, knowledge, capacity, judgment or efficiency in the person’s trade, business or profession.

There are a number of defences to defamation. Network Ten has submitted in court documents that it will seek to establish that the reporting was true and it will also rely on the defence of qualified privilege in the case.

Qualified privilege as a defence to defamation

Qualified privilege is where the defendant must prove that:

- the recipient of the information has an interest or apparent interest in having information on some subject, and

- the matter is published to the recipient in the course of giving to the recipient information on that subject, and

- the conduct of the defendant in publishing that matter is reasonable in the circumstances.

In determining whether the defendant’s conduct is reasonable, the court is to consider:

- the public interest in the matter, and

- whether the material relates to the performance of public functions, and

- the seriousness of any defamatory imputation, and

- whether the material distinguishes between suspicions, allegations and proven facts, and

- whether it was in the public interest to publish the matter expeditiously, and

- the nature of the business environment in which the defendant operates, and

- the integrity of the sources of the information;

- whether the substance of the material is person’s side of the story and, if not, whether a reasonable attempt was made by the defendant to obtain and publish a response from the person, and

- any other steps taken to verify the matter published, and

- any other circumstances that the court considers relevant.