Why the NSW Court of Appeal Declared the Protest to Be Legal

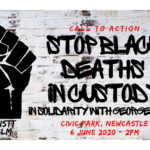

Looking out from Sydney Town Hall steps at 2.40 pm on 6 June the size of the crowd gathered for the Stop All Black Deaths in Custody-Black Lives Matter rally was staggering.

But, the thousands there were all about to break the law as the NSW Supreme Court had ruled it couldn’t go ahead.

Close to ten minutes later though, NSW Greens MLC David Shoebridge announced that he’d just been given the word that an appeal of the court ruling had been successful, so the 50,000 strong rally was now legal.

And the waves of jubilation that swept the crowd were almost palpable.

The Sydney barristers that argued the demonstration over the line were Stephen Lawrence and Felicity Graham. The pair had done so remotely from Dubbo, effectively saving all those present from being arrested or fined, which in this post-COVID-19 lockdown grey area can be quite steep.

Silencing dissent

On 29 May, Indigenous Social Justice Association (ISJA) secretary Raul Bassi emailed a Notice of Intention to NSW police commissioner Mick Fuller. It outlined his intention to hold a public assembly of around 50 people to mark the deaths in custody of David Dungay Junior and George Floyd.

Though, it became obvious the following week that the action was going to be much larger, as according to the Facebook event page, around 5,000 people would be attending and the scheduled meeting place next to Central would have to be changed to somewhere like Sydney Town Hall.

So, on 4 June, Bassi met with NSW police chief inspector Paul Dunstan to inform him that the rally would now comprise of many more participants and organisers wanted to march from Town Hall to Belmore Park.

NSW police sergeant Hallett subsequently amended the original notice and then emailed it to Bassi.

But, on the day prior to the rally, the police commissioner moved to have the event banned in the Supreme Court. And Justice Desmond Fagan ruled the protest could not go ahead due to concerns over the COVID-19 pandemic, drawing on evidence from NSW chief health officer Kerry Chant.

The law in application

The laws that allow for the authorisation of a public assembly are contained in part 4 of the Summary Offences Act 1988 (NSW). Section 23 outlines that a rally organiser must present an official notice to the commissioner outlining details at least seven days prior to its scheduled date.

Amendments of the details of a sanctioned assembly are then able to be made, under section 24 of the Act if the commissioner agrees to those changes. And section 26 sets out that if a notice is served less than seven days before an assembly, a court must then provide authorisation.

On 5 June, Justice Fagan found that Fuller hadn’t agreed to the amended notice and the changes to the event created a new one, which hadn’t been lodged seven days earlier. His Honour then refused an oral application for authorisation from Bassi on the basis of public health considerations.

Sydney lawyers step in

Protesters vowed to go ahead regardless. But, determined to overturn the ban, barristers working on behalf of Bassi lodged an urgent appeal with the Supreme Court just before noon on 6 June, about three hours before Sydney rallied for an end to police brutality towards First Nations people.

The appeal was argued on four grounds: that the justice had been in error in finding that the form hadn’t been lodged within the set time, that the changes had led to a new notice, that the commissioner hadn’t approved the amended notice, and that court authorisation was needed.

The barristers argued these points before Justices Tom Bathurst, Andrew Bell and Mark Leeming, who all agreed that the first three grounds of appeal had been made out, and due to this, there was no need to consider whether the fourth ground held any weight.

The panel of justices ruled that Bassi had given a notice of intention to hold a public assembly more than seven days prior to it taking place, and while the changes made were very significant, they didn’t lead to the original notice ceasing to legally apply and nor did the changes create a new one.

Their Honours noted that under section 24, the “particulars” of a public assembly may be altered with the agreement of the commissioner, and what occurred on 4 June with the changes was an alteration of the particulars, as opposed to the creation of a new form requiring court authorisation.

The justices then turned to the language used by sergeant Hallett in the email containing the final iteration of the notice of intention, which set out that the document was dated “29/5/2020” and that it had been “modified” on the “04/06/2020″.

The notice contained in the email therefore constituted the original one with the implied authorisation from the police commissioner.

“At some point between the sending of this email on 4 June 2020 on which Mr Bassi was entitled in the circumstances to rely upon and 5 June 2020, the commissioner’s view as to the advisability of the public assembly going ahead changed,” the Supreme Court justices found.

And an attempt by the commissioner’s lawyer to argue for a cross-appeal to the decision to allow the rally to go ahead during the course of the proceedings was dismissed in part due to the fact that it was raised only 20 minutes before the event was set to take place.

The machine continues

But, this hasn’t discouraged NSW authorities in their assault upon public political expression under the cover of COVID. NSW police minister David Elliott said on Monday that he expects protests over 10 people to be deemed illegal.

While on Wednesday, the NSW police commissioner again petitioned the state Supreme Court to prohibit another rally. This time the protest set to take place on Saturday afternoon at Sydney Town Hall is over the ongoing incarceration of refugees.

Justice Michael Walton ruled the demonstration should not go ahead due to the continued threat of the coronavirus. However, protest organisers have vowed that it will take place.