Witch-Hunting Is Gender-Based Violence: Talking Women’s Rights With India’s North East Network

Witch-hunting is a form of communal violence that continues in some parts of the world, including the state of Assam in Northeast India.

It almost always targets women, can act as punishment for tragedies with no direct relation to the accused “witch”, and it destroys the victim’s life and often takes it.

These days, witch-hunting is a criminal offence in Assam. Indeed, since the Assam Witch Hunting (Prohibition, Prevention and Protection) Act 2018 came into effect, about ten offences relating to the practice operate, with those causing death carrying life imprisonment or the death penalty.

The outlawing of witch-hunting was the result of civil society groups holding dialogues with state officials, and key to the campaign was the work of women’s rights organisation North East Network in co-producing clear documentation to prove the practice was a form of gender-based violence.

NEN was established in Assam in 1995 to address violence and discrimination towards women in all its forms, not only via the criminalisation of certain behaviours, but in a broader sense, by changing societal attitudes and inequalities to create a gender-just society.

A holistic approach

North East Network has forged a whole-of-society approach to upholding the human rights of women in the regions it operates in. NEN engages with grassroots communities and has established strong ties with the authorities via its evidence-based approach in creating reform.

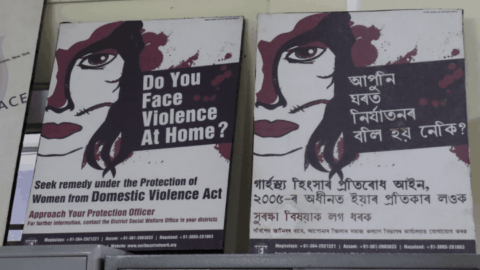

In the state of Assam, NEN has established a network of village-level support centres, which act as safe spaces for women experiencing domestic violence. These are run by local women trained in psychosocial counselling, who provide assistance to victim-survivors.

And another recent achievement took place during the pandemic, when NEN brought the escalation in domestic violence that was happening under the lockdown to the attention of government, which, in turn, saw it create a series of protocols focused on providing access to women’s shelters.

North East Network now operates in three northeastern states of India: Assam, Meghalaya and Nagaland. And over the year 2020/21, it assisted over 6,200 women and saw the various state governments approve more than 1,500 applications.

Shifting attitudes

Guwahati, the capital of Assam, is where NEN is headquartered. And walking through the streets the sense that women’s rights are being upheld seems palpable, whether that be with the presence of the region’s only All Women Police Station, or the numbers of women lawyers outside the courts.

NEN Assam state coordinator Anurita P Hazarika explains that the heads of the local police department were very open to discussions around the criminalising of witch-hunting, which was simply a community norm in parts of the region, once the evidence was before them.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers sat down to speak with Anurita and NEN project consultant Nilanju Dutta about the process of outlawing witch-hunting, the impact their organisation has had over the decades, and how NEN also focuses on assisting women in becoming economically independent.

North East Network was one of the organisations that helped influence this state’s government to pass the Assam Witching Hunting Act 2018.

How did you go about helping to facilitate laws against a cultural practice that was so entrenched in this region?

Anurita: North East Network doesn’t work directly with rescue and rehabilitation of survivors of witch-hunting.

But what we have done is partnered with one local organisation Assam Mahila Samiti Society and Partners in Law and Development, New Delhi that provided us with technical input to conduct qualitative research on witch-hunting of women in Assam.

Witch-hunting is a gender-based crime committed on women. It is gender-based violence on women. And North East works on gender-based violence, as it is one of our thematic areas.

So, we decided to do a study with AMSS. The study was qualitative in nature, not quantitative. It was based on newspaper clippings and secondary review, and we also conducted interviews with women and families affected by witch-hunting

What we learnt was more than 90 percent of cases are about women.

Like other violence which exists in patriarchal societies, witch-hunting is one form of violence. Any form of violence is used as a tool to keep women under control.

There were other issues of governance as well. For example, the police officers that were conducting the investigations would also belong to the communities.

So, there was this strong belief that witch-hunting is cultural and social, so the police would also maintain that status quo as they were under tremendous pressure to go by whims of the community.

There was no going forward, rather it was moving backwards. But now with the Act in place, the investigations are stricter.

We decided to have a dialogue with the government, so what we did with our study was shared it with officials from the Police Department like Ms Violet Baruah, who has now retired and the then Director General of Police Mr Mukesh Sahay. They were very open to the suggestions we made.

He very welcoming and willingly listened to our women’s voices and read through our entire report, which was from a feminist perspective, about how witch-hunting is a gender-based crime on women.

That was the first step we took. Then Assam Mahila Samiti Society facilitated a meeting with civil society organisations and various government departments, like police, the social welfare department and the women’s commission.

During that the government shared the draft bill in 2015, and we were very happy to see that some of the components featured were our findings from this particular study. So, we were very happy to see that.

From there, we were given a timeline by the government to give our input, and finally it was passed by the state assembly, and it remained in the form of a bill until 2018, when it was passed.

So, that was the role. One, we recognised it as gender-based violence. Number two, we wanted to create a study, so it could become a tool to have dialogue with the government. And thirdly, we partnered with local organisations, and we got an opportunity to put our viewpoints into the draft.

Why was getting laws like this across the line such a priority? What sorts of behaviours are we talking about?

Anurita: Witch-hunting is steeped in superstition. The whole community would participate and target women.

The community would have men, women, children, police and local officials, everybody believed in it. But there was no one particular legal instrument that captured witch-hunting as a crime. Now we have the Act, it’s a gender-neutral law for both men and women.

So, our dialogue was specifically about having a law about witch-hunting women. There are also witch-hunting laws in Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh.

And what would happen to a woman if she was branded a witch?

Nilanju: She would be humiliated publicly and made an outcast. There would be tonsuring. She would be paraded naked through the community. And women are also killed over this.

Anurita: There are many consequences of witch-hunting. So, adding to what Nilanju said, they would be thrown away from the village. They would be subjected to sexual violence, like rape.

We came across a case, in which this woman was raped and killed and acid from a battery was thrown on her, and her body was just lying there in one remote place. They are subjected to great violence.

There’s also boycotting, taunting, humiliation.

Nilanju: But it’s not only the women who are targeted. There are the family members as well. They will kill them and hang them too.

Anurita: Yes, there are collateral damages. For instance, once a witch, always a witch. So, what will happen, even with daughters, people would prefer not to marry them because she is the daughter of a witch.

So, it affects generations. Children won’t be admitted into schools. They have no access to the common grounds. There are many impacts, and much is lost.

Why are women targeted as witches? Because some women may have some property, even in the sense of a hut or a piece of land, so if they want to usurp that little property of the woman, they would assert that she’s a witch, then a local traditional healer or quack would be called to identify her as one.

So, much of it is to do with property. It can also be to do with women who are seen as too assertive and have a free and independent mind of their own, like if they turned down a marriage proposal, they might get targeted.

Then there can be diseases or children can die, and then someone will get into a trance and identify the witch. These are some ways that witch-hunting happens.

So, we thought it necessary to have a piece of legislation that would capture it as a crime. And also, there are other issues which needed attention like victim compensation by the state for affected victims to rebuild their lives.

The government updated its victim compensation scheme and included witch-hunting as a category of crime that needs to be compensated.

NEN was established in 1995. Anurita, you’ve been associated with the organisation since then.

A first of its kind organisation in Northeast India, NEN now also operates in Nagaland, Meghalaya, as well as here in Assam.

What sort of issues does NEN focus on? And how has this progressed over the last 27 years?

Nilanju: North East has always focused on working under three thematic areas.

The first thematic area focuses on addressing gender-based violence and discrimination against women and girls.

Another thematic area is where we focus mostly on good governance and state accountability. And the third thematic area is natural resource management and adding to that now we have started focusing on sustainable livelihoods options for women.

So, NEN is basically working on these thematic areas.

Anurita, I read your April 2020 article Lockdown: Locked With the Abuser, which discussed how women were at times breaching the lockdown to escape escalating domestic violence, and how your organisation was able to help them.

Can you talk about what happened during this period?

Anurita: In March to April 2020, there was the lockdown, and the priority of the government was to actually control the spread of the disease. The lockdown was unprecedented, so it got everybody nervous: the government, society and families.

But there was no priority on the gender needs of women. And people actually could not predict that this would lead to a rise in violence against women: that as people were locked up in their homes, homes of women became the most unsafe places.

The reasons for that in India, in our society, one of the cornerstones of gender-based violence are the unequal relations between men and women in the society.

The pandemic actually reinvented itself on these existing gender inequalities. So, that situation was aggravated.

When they were locked inside, there were untold increases in violence. As well, many families suffered because their incomes had dwindled, they were laid off and that entire frustration was let out on women.

And lastly, the government’s priority was very different at that point in time, that was to control the spread of the virus which of course was necessary.

So, we at North East Network, because we were working closely with the Social Welfare Department, we wrote a report on what was happening with women and the SWD commissioner was very responsive.

The commissioner immediately got a team together working to provide standard operating procedures (SOPs) for women facing violence and their access to shelter homes in Assam. It was one of the earliest SOPs in this regard, and probably the first in the country.

Our partner organisations, like Syawam in Kolkata and Jagori in Delhi, referred to the Assam SOP to mobilise initiatives in their states.

NEN also has dialogues and interface with the government around law changes and service establishment.

Anurita: Because we’ve been established here for more than 27 years now, because of our credibility and our very strong position on women’s rights violations, there is a recognition for the work NEN does and its strategies, which are community-friendly, as it engages them.

Another reason is that our work is based on a lot of documentation and surveying. And lastly, what we do is we look at the gaps and then we have dialogues and make proposals to the government. This kind of interface is always important.

Even our counselling centres, which are out in the villages, are recognised by the government as service providers under domestic violence legislation.

So, what sort of impact has NEN had in terms of women’s rights over the close to three decades it’s been operating?

Anurita: In Nagaland, the establishment of the community resource centre in Chizami village is a milestone. The verdict on our good work was given by the community as they donated land for the centre.

Now this community has a space where women can come and upgrade their livelihood skills, where women can come and talk of their rights, and where youths can come and find a space.

So, we have youth collectives there, vendors collectives. We have weaver collectives and farmers’ collectives. Because in Nagaland, they have really been working on the recognition of women farmers and also on discrimination in terms of payments of wages. And they’ve been successful in that.

In Meghalaya, we have counsellors at the grassroots level. Meghalaya’s work started with a study on domestic violence in matrilineal society. There is this whole myth about matriliny: everything is fine and rosy in the life of a woman in a matrilineal society, which is not true.

So, North East Network demystified that by showing there is huge patriarchal control in matriliny.

Our study became a turning point to start our work on gender sensitisation, and state accountability and governance to train healthcare providers, educational institutions and the police on being more gender responsive on addressing violence against women.

In fact, one of the earliest gender components in a police training manual in Meghalaya was developed by North East Network.

In Assam, we have what is called the Gramin Mahila Kendra. Gramin means village. Mahila is women and kendra is centre.

We have been doing this work on mobilisation for the past 10 to 12 years. And today, they have emerged as safe spaces for women, and these safe spaces are where women are provided psychosocial care and counselling by the village women who have been trained on such counselling.

This is a huge achievement of ours. Inside the counselling centre, it’s very feminist in nature unlike many other counselling centres.

These places are led by the community women who are trained by NEN on different issues of gender violence, law, service and policies. And they are very empowering.

These spaces actually began in about four or five districts with 30 women. Now, we have more than 300 women, because we have support groups, peer leaders and survivors groups.

So, this is a huge success, and it is also recommended by the government, as I said, they are registered as service providers.

And lastly, more broadly, how has NEN changed attitudes in society?

Anurita: When we started it was just women and women’s organisations alone. Now we work with youth. Now we work with government. Now we work with the community.

We have introduced an engaging youth program using various cultural and creative mediums. We play sports to talk of gender equality, because if you want to stop gender-based violence, you need to talk to the newer generation.

That is something that we are doing, creating youth collectives.

Nilanju: We are a community-based organisation, and our focus has always been communities.

Now these safe spaces that we have created within the villages itself and the recognition that our centres are getting from the community people, that is our achievement.

Anurita: Also, the women in the villages, they claim their spaces in the public forums. For example, earlier committees that were committed to looking at crime and robbery in the villages had only men. But now our women members are also part of those committees.

So, the very recognition itself is a behavioural change. Economic programs may not contain gender-based violence as a component, but what we have done is linked up survivors of violence to income generation activities like weaving and farm-based activities.

Nilanju: Our work in Assam is holistic in nature because we don’t only provide psychosocial counselling. There is always a follow up to her GBV case post the counselling sessions.

Every woman, when they approach us for counselling and legal support, once we resolve her case, we don’t leave it at that. We also link her with income generating activities where she can sustain herself and her family members.

So, there is an interconnectedness to everything we do.