An Apprehended Violence Order, or ‘AVO’, is an order made by a court which is meant to deter a person who is suspected of engaging in abusive conduct towards another from repeating or continuing that course of conduct.

But while this sounds sensible, there are concerns AVOs are being used for unintended purposes – such as to bolster family law proceedings or unfairly punish or seek revenge against another – and that claims upon which many applications are based are exaggerated, one-sided or even fabricated.

Here’s all you need to know about AVOs in New South Wales.

What is an AVO?

An AVO is a court order that expressly prohibits a person (the defendant) from engaging in certain types of conduct against another person (the protected person) for a specified period of time.

It can be made on a provisional basis (before first court date), and interim basis (between court dates) or a final basis (at the end of the proceedings) and contains mandatory conditions that the defendant must not assault, threaten, stalk, harass, intimidate or intentionally or recklessly destroy or damage property or harm an animal belonging to or in the possession of the protected person. It may also include additional conditions.

While an AVO is not a criminal offence, knowingly contravening a condition contained in the order can amount to a crime.

Who can apply for an AVO?

An AVO application can be made by:

- The person seeking protection (protected person),

- The legal guardian of a person seeking protection,

- A police officer, or

- The Secretary of the Department of Communities and Justice, or a person the Secretary delegates, in the case of a child being subjected to enter into a forced marriage.

A police officer must apply for an AVO if:

- The officer suspects that a domestic violence offence or an offence of stalking or intimidation has occurred or is likely to occur, or

- A domestic violence or stalking or intimidation charge has been brought.

However, the officer does not have to make the application for an AVO if:

- The protected person is at least 16 years of age, and

- The officer believes the protected person already intends to make an AVO application or there are good reasons for not making the application.

The officer must keep written reasons if he or she believes there are not good reasons for making the application.

Types of AVOs

There are two broad categories of AVOs in New South Wales

Apprehended Domestic Violence Orders

Apprehended domestic violence orders, or ADVOs, are sought where the defendant has or had a domestic relationship with the protected person.

This includes where the defendant and protected person are or were:

- Married or in a de facto or intimate personal relationship,

- Living in the same household or were simultaneously long-term residents in a residential facility (other than a correctional centre or detention centre),

- In a carer relationship,

- Relatives: being father, mother, grandfather, grandmother, step father or mother, father or mother in law, son, daughter, grandson, granddaughter, step son or daughter, son or daughter in law, brother, sister, half brother or sister, step brother or sister, brother or sister in law, uncle, aunt, uncle or aunt in law, nephew, niece or cousin, or

- Part of an extended family or kin in the case of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders.

Apprehended Personal Violence Orders

Apprehended personal violence orders, or APVOs, are sought where there is no domestic relationship between the defendant and person seeking protection.

This includes where the person seeking protection is a neighbour, work colleague, business partner, friend or acquaintance.

What is the difference between a provisional, interim and final AVO?

AVOs may be ordered on a provisional, interim or final basis.

Provisional AVOs

Provisional AVOs are also called ‘telephone AVOs’ or ‘urgent AVOs’ and can be sought by police officers by communicating by phone, fax or email to a judge or senior police officer in the event an incident occurs which gives the applying officer good reason to believe the AVO is necessary for the safety and protection of the protected person, or to prevent substantial damage to the protected person’s property.

Interim AVOs are sought before the scheduled court date

Interim AVOs

Interim AVOs are orders that go from court date to court date.

Defendants can attend court and oppose interim AVOs, at which time a court will only grant the interim AVO if it is satisfied on the balance of probabilities that the AVO appears necessary or appropriate in the circumstances of the case.

Final AVOs

Final AVOs are, as the name suggests, ordered upon the finalisation of the proceedings – whether this is when the defendant agrees to the AVO (with or without admissions) or when after a defended hearing the court finds the requirements for the AVO to be met.

What needs to be established for a final AVO to be made?

A court will order a final AVO if it is satisfied ‘on the balance of probabilities’ (it is more likely than not) that:

- The complainant fears the defendant will stalk or intimidate them, or commit a personal violence offence against them,

- There are reasonable grounds for the complainant to fear such conduct, and

- The conduct is sufficient to warrant the making of the order.

The first element of actual fear does not need to be established if the complainant is a child or appears to the court to be suffering from appreciably below average intelligence.

Conditions and Duration of AVOs

What are the conditions of AVOs?

All AVOs must contain mandatory conditions, and may also include additional conditions.

Mandatory conditions

The mandatory conditions of all AVOs are that the defendant must not do any of the following to the protected person or anyone the protected person has a domestic relationship with:

- Assault or threaten them,

- Stalk, harass or intimidate them, or

- Intentionally or recklessly destroy or damage any property or harm an animal that belongs to them or is in their possession.

Additional conditions

A court has the power to impose any additional conditions it sees as necessary or desirable to ensure the safety and protection of the protected person and any children from domestic or personal violence.

Such conditions may relate to such matters as contact, parenting, movement and the possession of firearms, and include orders that the defendant:

- Must not approach the protected person or contact them in any way or at any place, unless the contact is through a lawyer, or is to attend accredited or court-approved counselling, mediation or conciliation, or is in accordance with a family law contact order or agreement in relation to a child,

- Must not approach the protected person for at least 12 hours after drinking alcohol or taking illicit drugs.

- Must not attempt to locate the protected person except as ordered by a court.

- Must not attend at the residence or workplace of the protected person, or another place specific by the court.

- Must not possess a firearm or prohibited weapon.

How long does a final AVO last?

An AVO can be specified to last as long as the court considers necessary to ensure the safety and protection of the protected person.

Unless otherwise specified, an apprehended personal violence order (APVO) will last for 12 months.

Unless otherwise specified, an apprehended domestic violence order (ADVO) will last for two years, or 12 months if the defendant was under the age of 18 years when the application for the order was first made.

A court has the power to order that an AVO remain in force indefinitely if it is satisfied that:

- The applicant has sought an indefinite order,

- The defendant was at least 18 years of age when the application for the order was first made,

- There are circumstances that give rise to a significant and ongoing risk of death or serious physical or psychological harm to the protected person or any of his or her dependants, and

- That risk cannot be adequately reduced by an AVO of limited duration.

However, all final AVOs are subject to variation and revocation applications, which can change the AVO conditions (including reducing the AVOs duration) or bring it to an end altogether.

Does an AVO made in NSW apply across Australia?

Apprehended domestic violence orders (ADVOs) made in New South Wales are nationally recognised and enforceable across Australia.

Apprehended personal violence orders (APVOs) made in New South Wales are not nationally recognised and are only enforceable in other Australian states and territories in which they are registered. These are known as ‘external protection orders’.

How can an AVO affect a person?

An AVO is not a criminal offence and having an AVO therefore does not result in a criminal conviction.

This means an AVO will not show up on a criminal conviction record check, such as a national police check, and will also not generally affect overseas travel.

That said, an AVO may show up on a full background check which can be required for certain positions of employment, such as those which require higher levels of security clearance.

Having an AVO can also have a range of other adverse consequences, over and above being required to abide by the prohibitions and restrictions contained in the order, and can also result in reputational damage.

Potential consequences of an AVO include:

Family law proceedings

Having to abide by an AVO which restricts access to children can have adverse consequences for parenting proceedings, potentially leading to less or even no contact with children.

Indeed, the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) makes clear that a party to parenting proceedings must inform the court of the existence of an AVO that involves or relates to a child, which is a matter the court can consider when determining the case.

Aggrieved partners will often use the fact an AVO is in place, or had been in place, to bolster applications for contact with children, and may even rely on the grounds for complaint contained in the AVO application to strengthen submissions to the effect that the person against whom an AVO was made engaged in abusive conduct during the relationship – which can affect the credibility of any assertion of general good character.

Such submissions can even impact on property disputes, painting the person against whom an AVO has been ordered as controlling and potentially undeserving of favourable treatment.

All of that said, it should be noted that many judges in the family law jurisdiction are aware that some aggrieved partners will attempt to use AVO applications as a means of gaining an advantage in parenting and property proceedings, and such improper use can backfire on vexatious or vengeful litigants inside the courtroom by undermining their credibility.

Civil proceedings

The fact an AVO is or had been in place, as well as the grounds contained in the order, are capable of being raised – if they are relevant to the facts before the court – in civil proceedings that relate to a range of disputes – from neighbourhood, to workplace, to those arising from business or other disagreements.

Firearms licences

The granting of an interim AVO – which is an offered that comes into effect before the first court date – will result in the suspension of a firearms licence or permit, and require the surrender of any firearms possessed.

The granting of a final AVO will result in a firearms licence being automatically revoked.

This can have a significant impact on those who require firearms for employment purposes such as policing or security, or to protect livestock on rural land.

Residential tenancies

The Residential Tenancies Act 2010 makes clear that the residential tenancy agreement of a tenant or co-tenant is terminated if a final AVO prohibits that person from accessing the subject premises.

The remaining tenant or tenants can apply to the New South Wales Civil and Administrative Tribunal for a fresh residential tenancy on such of the terms of the terminated agreement that the Tribunal thinks appropriate having regard to the circumstances.

Working with children

Adults who work in child-related positions must obtain a Working with Children’s Check (WWCC) every five years

Having an AVO can result in the Office of the Children’s Guardian refusing to issue a WWCC clearance or cancelling a clearance that has been issued, which of course can significantly impact upon or even prohibit working in a range of positions such as childcare, healthcare, education and certain sporting and residential services.

Any such refusal or cancellation can be appealed to the New South Wales Civil and Administrative Tribunal within 28 days of the decision.

Security clearances

Certain employment and contractual positions which deal with sensitive or classified information, such as many jobs within and related to government departments and agencies, will require full background checks, sometimes on a regular basis.

These checks will ordinarily disclose all criminal charges presently and historically brought including those that have been withdrawn or dismissed, as well as present and past AVOs.

Having a current or previous AVO may render a person ineligible for these positions.

Can a person with an AVO against them leave Australia?

Yes. Unless a specific condition in the AVO prohibits leaving the country, a person who has a provisional or interim AVO against them can go overseas, provided of course the person returns by a date on which they are required to attend court.

A person against whom a final AVO has been made can leave Australia unconditionally.

Defending an AVO

There are several ways to defend and AVO and thereby ensure a final AVO is not made.

These include:

Offering an undertaking

Negotiations can be undertaken with the applicant – whether this is the person seeking protection in a private AVO (or their lawyer) or the police informant in an AVO application made by police on behalf of the protected person – with a view to reaching agreement on written ‘undertakings’, also knows as promises to the court, not to engage in certain types of conduct (normally those specified in the AVO) for a specific period of time.

These undertakings are signed and handed-up to the court on the scheduled court date, at which time the applicant can seek to have the AVO withdrawn and dismissed.

Undertakings are not legally enforceable but will be kept on the court file and may be relied upon in making a fresh formal AVO application if any of the promises are breached.

Pushing for withdrawal

A formal letter known as ‘representations’ can be drafted and sent to the AVO applicant – whether this is the person seeking protection in a private AVO (or their lawyer) or the police informant in an AVO application made by police on behalf of the protected person – formally requesting withdrawal of the AVO application.

This document is normally followed up with negotiations pressing for withdrawal

This process will often occur where the grounds for the AVO application (the allegations) contain inconsistencies, deficiencies, or unsupported or factually incorrect assertions, and may be enhanced in circumstances where the person seeking protection provides what is known as a ‘retraction letter’ – which is a letter supporting the request for withdrawal and stating the reasons for that request.

It is important to be aware that, in the case AVO applications made by police on behalf of the protected person, only the police have the power to withdraw the application, not the person seeking protection.

If this course of action is agreed, the AVO will be formally withdrawn and dismissed in court.

Lapsing the AVO

There is a mechanism whereby a person against whom an application for an AVO has been made and who has no associated criminal charges may be able to have their case adjourned with a view to the AVO application ‘lapsing’; in other words, not having a final AVO made against them.

This mechanism is contained in the Specialist Family Violence List Practice Note and currently applies to cases listed in:

- Bankstown Local Court,

- Blacktown Local Court,

- Downing Centre Local Court,

- Gunnedah Circuit (excluding Tamworth),

- Liverpool Local Court,

- Moree/Inverell Circuit,

- Newcastle Local Court,

- Katoomba Local Court, Windsor Local Court, and

- Sutherland Local Court.

The Practice Note applies to all AVO applications where there are no associated criminal charges and empowers the court to adjourn the case and dismiss the AVO application on the subsequent court date provided there are no contraventions of the restrictions or prohibitions contained in the interim order.

The court may have regard to the following matters when deciding whether to impose a lapsing interim order:

- Whether the prosecutor and defendant consent to the order,

- Any views expressed by the complainant, including whether he or she has indicated they do not want a final order,

- Whether the complainant has received independent legal advice or engaged with support services,

- The nature of the relationship between the complainant and defendant,

- Any reconciliation between the complainant and defendant,

- The seriousness of the allegations contained in the grounds of the application and the conditions being sought,

- Whether such an order has been sought in the past,

- Any impacts associated with imposing the order instead of a final order,

- Whether the defendant is seeking treatment and/or counselling, and

- Any other matter/s the court considers appropriate.

If a defendant has agreed to engage with an appropriate counselling or intervention service, the court will record this agreement on file, and may take compliance or lack thereof into account when determining whether to lapse the AVO on the subsequent court date.

A complainant, defendant or police officer acting on behalf of a protected person can request that the proceedings be relisted at any time during the period of the adjournment – which will normally only occur if there is an alleged breach of the AVO.

The mechanism is important because it means there will be no final AVO, provided there is compliance with the AVO conditions during the adjournment period.

Participating in mediation

The court must refer the defendant and protected person to mediation where the case involves an application for an Apprehended Personal Violence Order (APVO) without associated criminal charges.

The AVO case will be adjourned to enable this to occur.

The mediation will take place at a Community Justice Centre where the parties will have an opportunity to discuss the case and how it may be resolved, without having to resort to a formal court hearing.

If an agreement is reached, a formal document will be signed which can be made enforceable during the next court date.

If an agreement is not reached, the case will proceed in the regular manner with a timetable being set for preparing and serving written statements, followed by a date to check compliance, and a hearing date after that.

Defending the AVO in court

Where an AVO case proceeds to a formal hearing, known as a ‘show cause hearing’, the applicant will need to establish ‘on the balance of probabilities’ (that is it more likely than not) that:

- The complainant fears the defendant will stalk or intimidate them, or commit a personal violence offence against them,

- There are reasonable grounds for the complainant to fear such conduct, and

- The conduct is sufficient to warrant the making of the order.

The first element of actual fear does not need to be established if the complainant is a child or appears to the court to be suffering from appreciably below average intelligence.

Where there are no criminal charges associated with the AVO, the written statements will be tendered to the court and be read by the judge.

These statements represent the ‘evidence in chief’ of each party; in other words, the testimony they would normally give on the witness stand if the case had involved criminal charges.

The protected person will then take the witness stand and be subjected to ‘cross examination’ (questioning) by the defence lawyer.

Cross examination is where the protected person’s testimony is challenged, which may involve lines of questioning regarding inconsistencies, unsupported or implausible assertions, questions of motive and credibility, and putting the defence position.

Any additional prosecution witnesses will go through the same process.

It is important to note that a defendant is not permitted to cross examine a witness who is a child – only a lawyer or other suitable person appointed by the court can do this.

Where associated criminal charges are also before the court, there will be no written statements, and the person seeking protection as well as any other prosecution witnesses will give their testimony on the witness stand and be subjected to cross-examination by the defence lawyer.

In either case, the defendant will then decide whether or not to take the witness stand and give their testimony.

If the defendant chooses to do this, he or she will be cross-examined by the prosecutor.

The defence can also call any additional witnesses, which will give their testimony and be subjected to cross examination by the prosecutor.

In all cases, the prosecution and defence will have the opportunity to make closing submissions at the end of the case, before the judge decides whether or not the AVO applicant has discharged its onus of establishing the necessary ingredients to the required standard.

If the AVO applicant proves its case, a final AVO will be made.

If the AVO applicant fails to prove its case, the AVO application will be dismissed.

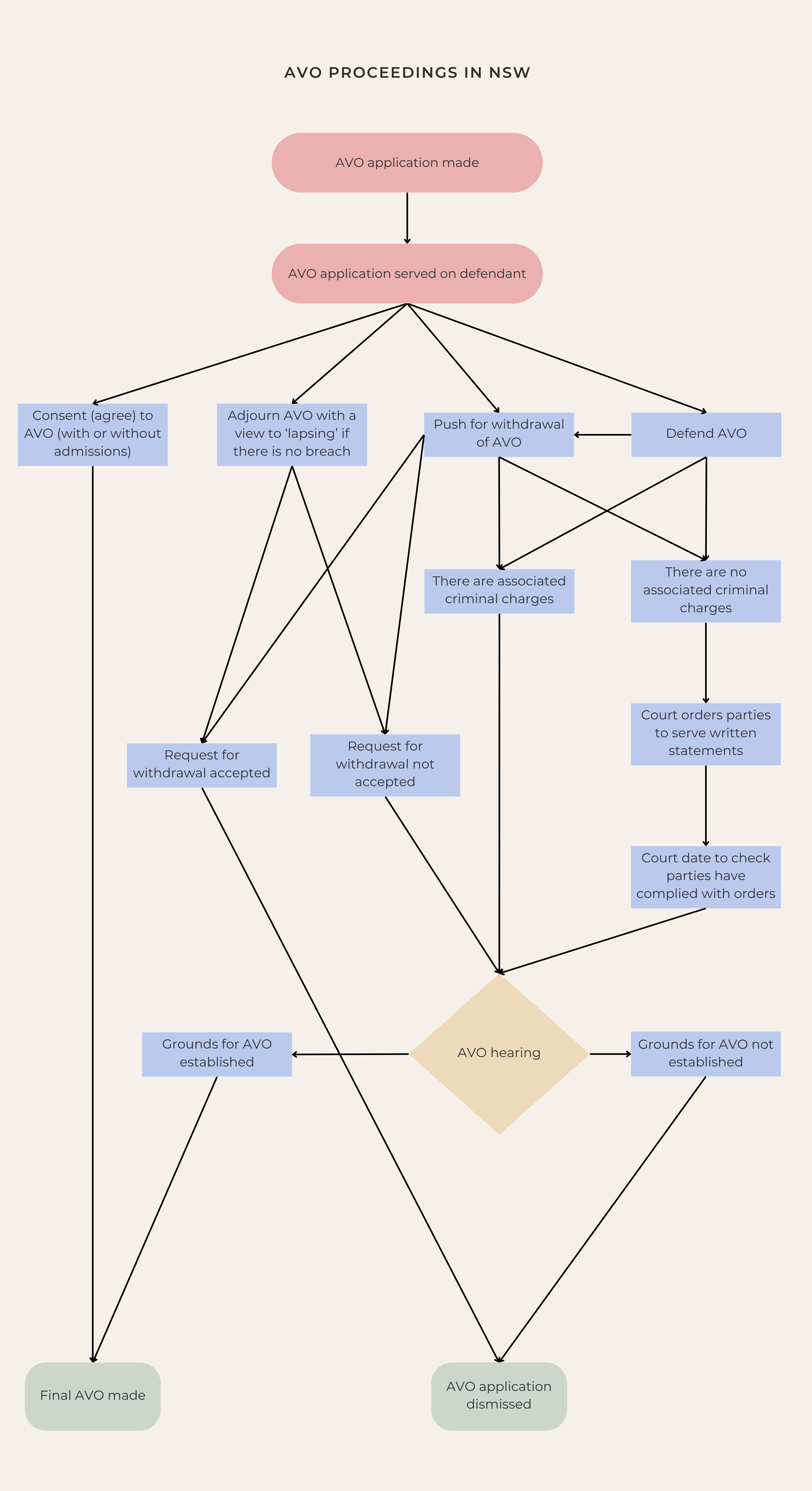

Court Process for AVO Cases

The court processes for AVO applications differ depending on a number of factors, including whether the application is for an apprehended personal violence order (APVO) or an apprehended domestic violence order (ADVO) as well as whether there are associated criminal charges; in other words, allegations of criminal offences that arise from the same circumstances as those contained in the grounds for complaint in the AVO.

Here is an outline of the court processes when defending an AVO application:

-

First court date

The first court date is known as a ‘mention’ – which is essentially an administrative court date where the future course of the case is determined.

The defendant is required to attend court on this date unless legally represented, in which case a lawyer can attend on his or her behalf.

AVO applications without associated criminal charges

If the application is for an APVO without associated criminal charges, the case will be adjourned to a later date and the parties will be ordered to undertake mediation at a Community Justice Centre with a view to resolving the matter without having to resort to a defended hearing.

However, a court will not order mediation if there are good reasons not to do so, which may include where:

- There has been a history of physical violence by the defendant towards the protected person,

- The defendant has engaged in conduct amounting to a personal violence offence or an offence of stalking or intimidation against the protected person,

- The defendant has harassed the protected person on the basis of race, religion, homosexuality, transgender status, disability or HIV/AIDS status, and/or

- There have previously been an unsuccessful mediation attempt.

In that event, a timetable will be set for written statements to be prepared by each of the parties.

These statements are capable of being used as evidence in court if the case proceed to a defended hearing.

This timetable will normally involve the applicant serving their written statements within two weeks, the defendant serving any statements relied upon within four weeks.

The case will be listed for a further mention date in five weeks to check compliance with the timetable.

AVO applications with associated criminal charges

If criminal charges are associated with the AVO application, the prosecution will be ordered to serve the brief of evidence – which includes witness statements and other materials relied upon to establish the criminal offence/s – and the case will ordinarily be listed for a readiness hearing as well as a contested hearing.

The purpose of the readiness hearing is to confirm that both parties are ready to proceed to hearing.

The readiness hearing will occur at least 14 days before the contested hearing.

AVO applications in the Specialist Family Violence List

If the case falls within the requirements of the Specialist Family Violence List Practice Note (see above), an interim AVO (one that applies between court dates) will be made and the case adjourned to determine whether the defendant has complied with the conditions of the order.

Contested interim AVOs

An interim AVO is one that applies between court dates.

A defendant may consent (agree) to or contest (oppose) an application for an interim AVO.

The court may order an interim AVO if it appears necessary or appropriate to do so in the circumstances.

The court must make an interim AVO if the defendant is charged with a serious offence, whether or not an application for an interim AVO has been made, unless the court is satisfied it is not required in the circumstances.

A registrar can only make an interim AVO if both parties consent.

Where protected person and defendant absent

Where an application for an interim AVO made by a police officer is contested and neither the protected person nor defendant are at court, the judge may consider an affidavit or written statement tendered on behalf of the protected person if the judge is satisfied there are good reasons for the protected person not attending court and the application requires urgent consideration.

Where protected person absent and defendant present

The same rule applies where an application for an interim AVO made by a police officer is contested and only the defendant is present.

That is, the judge may consider an affidavit or written statement tendered on behalf of the protected person if the judge is satisfied there are good reasons for the protected person not attending court and the application requires urgent consideration.

Where protected person present and defendant absent

A judge can make an interim AVO regardless of whether the defendant is at court or has been given notice of the proceedings.

Where protected person and defendant both present

Where the protected person and defendant are present at court and the interim AVO application is contested, a hearing of that application is to be held on the day or, if that is not possible, as soon as practicable thereafter.

The application is to be heard and determined based on:

- The written grounds of the application,

- Written statements from any witnesses intended to be called at the interim hearing,

- Oral evidence, and/or

- Written or verbal submissions in court.

As a general rule, any cross-examination of a witness at the interim hearing:

- Is limited to establishing whether it is necessary or appropriate to make an interim order, and

- Is not to be directed toward establishing whether a final AVO is warranted.

2. Second or subsequent court date/s before hearing

What occurs at the second or subsequent court date before any contested hearing also depends on the category into which the application falls.

AVO applications without associated criminal charges

If the AVO application had been adjourned for mediation, the court will ascertain participation as well as whether an agreement had been reached.

If so, the terms of that agreement can be formally accepted, whether this involves:

- Dismissing the AVO application unconditionally,

- Dismissing the AVO application upon receipt of undertakings to the court,

- Making a final AVO on the existing conditions, or

- Making a final AVO on varied conditions.

This will bring an end to the proceedings.

If no agreement had been reached, a timetable will be set for the service of statements as described above and the case will be adjourned to check compliance with those orders.

If a timetable had been set during the first court date, the court will determine whether there has been compliance with those orders.

If so, the court will adjourn the case for a contested hearing.

If not, the court may:

- Dismiss the AVO application if the applicant has failed to comply,

- Make a final AVO if the defendant has failed to comply, or

- Set a further timetable and adjourn the case for another compliance check, if there are good reasons to do so.

AVO applications with associated criminal charges

AVO applications with associated criminal charges will come before the court for a readiness hearing, with a view to ascertaining whether both parties are prepared for the contested hearing.

If the parties are ready, or anticipate being ready by the hearing date, the hearing date will be confirmed.

If the parties are not ready and do not anticipate being ready, an application can be made to vacate (cancel) the hearing date.

Such an application will only be successful if vacating the hearing is in the interests of justice.

If the application is successful, further dates for readiness and hearing will be set.

Alternatively, the court has the power to adjourn the case for mention on a date closer to the hearing, with a view to ascertaining readiness.

AVO applications in the Specialist Family Violence List

Where an AVO application was adjourned in the Specialist Family Violence list subject to an interim order, the court will ordinarily be withdrawn by the prosecution and dismissed by the court provided there has been no breach of the orders.

If there has been a breach of the orders, the lapsing AVO order may be revoked and a timetable set for the service of written statements, followed by a date to check compliance at which time further court dates for a readiness hearing and contested hearing will be scheduled.

3. Contested hearing

The process that takes place at a contested hearing – which is also known as a show cause hearing – will differ depending on whether associated charges accompany the AVO application.

Where there are no associated criminal charges

Where there are no criminal charges that arise from the same circumstances as the grounds of the AVO application, the contested hearing will proceed with the written statements of the complainant – also known as the protected person or person seeking protection – and any other of the applicant’s witnesses being tendered in court.

These statements represent the evidence-in-chief of the applicant; in other words, the primary evidence being relied upon to establish the requirements of the AVO application.

Applicant’s case

The applicant will then open its case and the statement of the complainant will normally be read first.

The defence will then have the opportunity to cross-examine the complainant; in other words, ask them questions with a view to challenging their evidence, raising inconsistencies, unsupported assertions, deficiencies, matters impacting on credibility and so on, with a view to undermining the evidence.

This process will be repeated with any other applicant witnesses.

It is important to note that only a legal practitioner (lawyer) or other suitable person appointed by the court can cross-examine a witness who is a child, or who in the opinion of the court suffers from an appreciably low level of intelligence.

The applicant will then close its case, and the defence will be invited to open its case.

Defence case

Provided the defence is of the view at this stage that the requirements for the AVO application are capable of being established on the balance of probabilities, the defendant’s statement will ordinarily be tendered and – in the same way as the statement/s for the applicant – relied upon as the defendant’s evidence-in chief.

The applicant will then have the opportunity to cross-examine the defendant.

This process will be repeated with any other defence witnesses.

Closing submissions

Each party will then have the opportunity to make closing submissions to the court – the applicant submitting that the evidence establishes the requirements for the AVO to the required standard, and the defence submitting that it does not.

Judge’s deliberations

The judge will then consider whether the applicant has established on the balance of probabilities that:

- The complainant fears the defendant will stalk or intimidate them, or commit a personal violence offence against them,

- There are reasonable grounds for the complainant to fear such conduct, and

- The conduct is sufficient to warrant the making of the order.

It is important to be aware the first element of actual fear does not need to be established if the complainant is a child or appears to the court to be suffering from appreciably below average intelligence.

When deciding whether to grant an application for an AVO, the judge must consider the safety and protection of the complainant as well as any child directly or indirectly affected by the defendant’s conduct.

This encompasses consideration of:

- The effects and consequences on the safety and protection and any child permanently or ordinarily living at the residence, if an order that prohibits or restricts access to the residence is being requested,

- Any hardship that may be caused by making the order, particularly to the complainant and any child, and

- The needs of all parties, particularly the complainant and any child.

Judgement

The judge will then deliver the judgement, informing the parties as to whether he or she considers the requirements of the AVO application to have been established, as well as the reasons for making that decision.

If the requirements are established, a final AVO will be ordered.

If they are not, the AVO application will be dismissed.

Where there are associated criminal charges

Where criminal charges that arise from the same circumstances as the grounds of the AVO application are being heard simultaneously, the criminal and AVO proceedings will proceed in accordance with a defended criminal hearing.

This means that, unlike where there are no associated criminal charges, written statements will not be tendered as evidence-in-chief.

Rather, the prosecution and defence will have the opportunity to make opening statements which foreshadow the evidence to be adduced. The parties do not have to make such statements.

Prosecution case

The prosecution will then call its first witness.

The prosecution witnesses will ordinarily include the officer in charge of the case and complainant, as well as any others that are intended to give testimony supporting the allegations.

These witnesses will give their evidence-in-chief on the witness stand; in other words, be asked to give their version of the events.

The defence will then be able to cross-examine each witnesses after he or she has testified; that is, question them with a view to challenging their testimony, raising inconsistencies, unsupported assertions, deficiencies, matters impacting on credibility and so on, with a view to undermining the evidence.

The prosecution will then close its case.

No prima facie case submission

If the defence is of the view the prosecution evidence when taken at its highest is incapable of establishing the criminal charges, a no prima facie case submission can be made at this stage.

If the submission is accepted, the criminal charges will be dismissed. However, this does not prohibit the making of a final AVO as the standard of proof for an AVO application is lower than that of a criminal prosecution.

That being so, the judge can proceed with the hearing of the AVO application despite dismissing the criminal charge/s.

Defence case

The defence will then be invited to call any witnesses to the stand, including the defendant.

The defendant will only normally be called if the defence is of the view the prosecution evidence is likely to have established the charge/s beyond a reasonable doubt.

If a defence witness is called to testify, the witness will be asked questions by his or her own lawyer, which is known as evidence-in-chief.

The prosecution will then have the opportunity to cross-examine the witness.

Closing submissions

The prosecution and defence will then have the opportunity to make closing submissions to the court, in relation to both the criminal charge/s and the AVO application.

Judge’s deliberations

The judge will then consider whether the prosecution has proven the charged criminal offence/s beyond a reasonable doubt.

The judge will separately consider whether the applicant has established ‘on the balance of probabilities’ (it is more likely than not) that:

- The complainant fears the defendant will stalk or intimidate them, or commit a personal violence offence against them,

- There are reasonable grounds for the complainant to fear such conduct, and

- The conduct is sufficient to warrant the making of the order.

The first element of actual fear is not required to be established if the complainant is a child or appears to the court to be suffering from appreciably below average intelligence.

When considering the AVO application, the judge must take into account the safety and protection of the complainant as well as any child directly or indirectly affected by the defendant’s conduct.

This encompasses consideration of:

- The effects and consequences on the safety and protection and any child permanently or ordinarily living at the residence, if an order that prohibits or restricts access to the residence is being requested,

- Any hardship that may be caused by making the order, particularly to the complainant and any child, and

- The needs of all parties, particularly the complainant and any child.

Judgement

The judge will then deliver the verdict in the criminal case; in other words, inform the parties whether the defendant is guilty or not guilty.

Following this, the judge will deliver judgement on the AVO application; that is, inform the parties whether the requirements of the application have been met.

If so, the judge will make a final AVO.

If not, the judge will dismiss the AVO application unless required to make the final AVO by law.

Court must make AVO on finding of guilt for an associated serious offence

In that regard, it is important to be aware that – unless there are good reasons not to do so – a court must make a final AVO if there is a finding of guilt for an associated ‘serious offence’, which encompasses:

- Attempted murder,

- A domestic violence offence other than murder, manslaughter or assault causing death.

A domestic violence offence is one that is committed against another person with whom there is or has been a personal violence offence, or an offence that arises from substantially the same circumstances as a personal violence offence, or an offence of section 54D(1), or an offence other than a domestic violence offence that involves domestic abuse.

A personal violence offence is one that is under, or mentioned in, the following sections of the Crimes Act 1900: 19A, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 33, 33A, 35, 35A, 37, 38, 39, 41, 43, 43A, 44, 45, 45A, 46, 47, 48, 49, 58, 59, 61, 61B, 61C, 61D, 61E, 61I, 61J, 61JA, 61K, 61KC, 61KD, 61KE, 61KF, 61L, 61M, 61N, 61O, 65A, 66A, 66B, 66C, 66D, 66DA, 66DB, 66DC, 66DD, 66DE, 66DF, 66EA, 73, 73A, 78A, 80A, 80D, 86, 87, 91P, 91Q, 91R, 93AC, 93G, 93GA, 110, 195, 196, 198, 199, 200, 562ZG or the former offence under section 562I, or 109, 111, 112, 114, 115 or 308C but only if the offence is in the nature of the previous-mentioned offences, or an offence of stalking or intimidation under section 13 or contravening an AVO under section 14 of the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007, or an offence of forced marriage under section 270.7B of the Criminal Code Act 1995, or any attempt to commit one of the mentioned offences.

Domestic abuse encompasses violent, threatening, coercive or controlling behaviour, as well as conduct that causes another to fear for his or her safety or wellbeing, or that of others.

- Any offence under, or mentioned in, section 33 (intentionally wounding or causing grievous bodily harm) or 35 (recklessly wounding or causing grievous bodily harm) of the Crimes Act 1900,

- A prescribed sexual offence, which includes the offences contained in the following sections of the Crimes Act 1900: 43B, 45, 45A, 61B, 61C, 61D, 61E, 61I, 61J, 61JA, 61K, 61KC, 61KD, 61KE, 61KF, 61L, 61M, 61N, 61O, 63, 65, 65A, 66, 66A, 66B, 66C, 66D, 66DA, 66DB, 66DC, 66DD, 66DE, 66DF, 66EA, 66EB, 66EC, 66F, 67, 68, 71, 72, 72A, 73, 73A, 74, 76, 76A, 78A, 78B, 78H, 78I, 78K, 78L, 78M, 78N, 78O, 78Q, 79, 80, 80A, 80D, 80E, 81, 81A, 81B, 87, 89, 90, 90A, 91, 91A, 91B, 91D, 91E, 91F, 91G, 91P, 91Q, 91R, 316 (if the concealed serious indictable offence is a prescribed sexual offence) or 316A

- Any offence under section 93AC (child forced marriage) of the Crimes Act 1900 or the Commonwealth Criminal Code, section 270.7B (forced marriage offences), or

- an offence of attempting to commit an offence referred to in paragraph (b), (c), (c1a) or (c1),

- Any offence of stalking or intimidation with the intention of causing physical or mental harm, or

- An offence under the law of the Commonwealth, another State or a Territory, or another country, that prescribes an offence similar to the above.

In the event a full-time prison sentence is imposed, the ADVO will remain in place for two years after the prison term ends, unless the court orders otherwise.

Where the defendant was under the age of 18 years at the time of the offending, the court is not required to order a final AVO unless the person is sentenced to a term of full-time imprisonment.

Flowchart of AVO proceedings

What happens if the protected person fails to attend court?

There may be consequences for a complainant (the person seeking protection or protected person) who fails to attend court.

Failing to attend the first court date

Where the protected person fails to attend the first court date for an AVO application made on their behalf by police, the judge will only make an interim AVO (an AVO that applies between court dates) if the defendant consents, or if police are able to establish by way of affidavit evidence or a written statement that there are good reasons for the protected person not attending court and the matter being one which requires urgent consideration.

Where the protected person in a private AVO fails to attend court, the judge has the power to adjourn the application or dismiss it altogether.

Failing to attend a second or subsequent preliminary court date

Where the applicant in an AVO application without associated criminal charges fails to comply with the timetable for serving written statements, the judge can dismiss the application altogether or, if there are good reasons to do so, set a further timetable for service of the statements and adjourn the case to check compliance.

Failing to attend the hearing date

Where the protected person fails to attend court on the day of the contested hearing, the judge may:

- Dismiss the application altogether,

- Adjourn the application to allow the protected person to attend, but only if this is in the interests of justice, or

- Proceed to hear and determine the case on the grounds contained in the AVO application and any written statements provided to the court by a police officer, as well as defence statements (if the defendant is present) and/or the defendant’s testimony, if the protected person had notice of the hearing date and it is in the interests of justice to proceed on the day.

What happens if the defendant fails attend court?

The potential consequences of the defendant failing to attend court as required are as follows:

Failing to attend the first court date

Where the defendant fails to attend the first court date and is not legally represented, the court may:

- Make an interim AVO and adjourn the case (with or without setting a timetable for service of written statements where there are no associated criminal charges), or

- Make a final AVO, but only if the court is satisfied the defendant had been given reasonable notice of the hearing date, time and place and it is in the interests of justice to do so.

Failing to attend a second or subsequent preliminary court date

Where the defendant in an AVO application without associated criminal charges fails to comply with the timetable for serving written statements, or to attend or have legal representation in court, the judge can make a final AVO or, if there are good reasons to do so, set a further timetable for service of the statements and adjourn the case to check compliance.

Where the defendant in an AVO application with associated criminal charges fails to attend court or have legal representation in court, the judge has the power make a final AVO, but only if satisfied the requirements for making a final AVO are met.

Failing to attend the hearing date

Where the defendant fails to attend court on the day of the contested hearing, the judge may:

- Vacate the hearing and re-list in on another day. However, this will only occur in exceptional circumstances such as where the court is of the view the defendant did not have notice of the hearing date, or

- Proceed with the hearing in the defendant’s absence on the grounds contained in the AVO application as well as any written statements, provided the defendant had been given reasonable notice of the hearing date, time and place. A final AVO will be ordered if the court is satisfied the requirements for making it are met.

Applying for an AVO

The process for making an AVO application depends on whether the order is sought by police on behalf of a protected person, or privately by a complainant.

AVO applications made by police

Those who fear for their personal safety can contact police with a view to having an AVO application made on their behalf.

Police will normally arrange for an interview to take a formal statement and assess the allegations.

A police officer will then decide whether to make an application by phone, fax or other communication device to an authorised officer – being a registrar or judge of a Local Court, or a senior police officer – for a provisional AVO; which is an AVO that applies for 28 days or until the first court date, whichever comes first.

A police office may apply for a provisional AVO if an incident has occurred between the complainant and suspect which gives the officer good reason to believe the AVO is immediately necessary to ensure the safety and protection of the complainant, or to prevent substantial damage to the complainant’s property.

The authorised officer will grant the provisional AVO if satisfied there are reasonable grounds for doing so.

If granted by a senior officer, the provisional AVO will be filed in court and taken as a general AVO application, and a first court date will be set.

A first court date will similarly be set if the provisional AVO is granted by a court registrar or judge.

The provisional AVO must be served on the defendant as soon as practicable, and will only come into effect once it is served.

The AVO is to be served on the defendant personally, but may be served by electronic means, such as by email, if:

- The defendant or protected person consent, and

- The police officer personally explains to the defendant or protected person the conditions and consequences of breaching any condition in the AVO, as well as associated rights.

A police officer who is investigating an incident must apply for a provisional AVO if the officer suspects or believes that:

- A domestic violence offence or an offence of stalking or intimidation with intent to cause physical or mental harm has recently been or is being committed, or is imminent, or is likely to be committed against the person for whose protection the order would be made, or

- An offence of child and young person abuse has recently been or is being committed, or is imminent, or is likely to be committed against a child or young person for whose protection the order would be made, or

- Proceedings for any of the above offences have been commenced where the person for whose protection the order would be made is the alleged victim,

And the officer has good reason to believe an order needs to be made immediately to ensure the safety and protection of the person who would be protected, or to prevent substantial damage to that person’s property.

An officer must apply for proceedings to be commenced seeking a final AVO if the three dot points above are satisfied; in other words, there is no additional requirement of a ‘good reason’.

However, an officer does not need to apply for an AVO in such circumstances if:

- The person for whom the order would be made is at least 16 years old, and

- The officer believes the person intends to make an AVO application or there are good reasons not to make the application.

The officer will need to make a record of the good reasons for not making the application, and the unwillingness or reluctance of a person to have an order made for their protection will not generally suffice.

Investigating police will often bring associated criminal charges against the defendant, such as assault charges.

If such charges are brought, the proceedings will ordinarily be listed on the same date and in the same court as those for the AVO application.

The AVO application will then proceed in accordance with the court process previously outlined.

Private AVO applications

A private AVO is one that is sought directly by a person aged at least 16 years who is seeking protection, rather than by police on behalf of such a person.

AVO application forms come with step-by-step guides and can be obtained from a Local Court registry.

The applicant can arrange to attend the court registry to submit the forms once they are completed.

A court registrar will then review, sign and process the application, unless the registrar refuses to do so.

A registrar has discretion to refuse to process an application for an apprehended personal violence order (APVO) that is not made by a police officer if satisfied the application:

- Is frivolous, vexatious, without substance or has no reasonable grounds of success, or

- Could be dealt with more appropriately by mediation or another means of dispute resolution.

A court registrar, judge or senior police officer is, unless there are compelling reasons to do so, prohibited from refusing to process a private AVO application that discloses:

- A personal violence offence,

- An offence of stalking or intimidation with intent to cause physical or mental harm,

- Harassment relating to race, religion, homosexuality, disability, or transgender or HIV status, unless there are compelling reasons to do so,

When determining whether to process a private AVO application, a judge or court registrar must take into account:

- The nature of the allegations,

- Whether there are prospects of mediating or otherwise resolving the matter without having to continue the proceedings,

- Whether the parties have previously attempted mediation or another form of dispute resolution,

- Whether mediation or other alternative dispute resolution services are available and accessible,

- Whether the parties are willing and capable of resolving the matter in a way other than having to continue the proceedings,

- The relative bargaining power of the parties,

- Whether the application is a cross-application, being one made in response to an initial AVO application, and

- Any other relevant matter.

The reasons for any refusal by a court registrar to process an AVO application must be recorded in writing.

The applicant may apply to have any such decision determined by a Local Court judge.

Revoking, Varying or Appealing an AVO

Can an AVO be revoked or varied?

An application can be made to revoke (cancel) or vary (change the prohibitions or restrictions) in a provisional, interim or final AVO.

Revoking or varying a provisional AVO

A provisional AVO is one that applies for 28 days or until the first court date, whichever comes first.

Any interested party may apply to a court to revoke or vary a provisional AVO, including the defendant, protected person/s or police.

However, only a police officer can apply for revocation or variation of a provisional AVO where a protected person is a child.

A provisional AVO may be varied or revoked by the authorised officer who made it, or by any court before which the case comes before.

Variations may be in the form of amending, deleting or adding prohibitions and/or restrictions to the AVO.

Notice of any application for revocation or variation must be served on the defendant, each protected person and the Commissioner of Police.

Where a defendant applies to revoke or vary a provisional AVO made by a senior police officer, the application will come before the court in which it is listed.

The court may revoke or vary the provisional AVO if satisfied that in all the circumstances it is proper to do so.

A provisional AVO is not to be varied or revoked on the application of the defendant unless notice is served on the relevant Police Area Commander or Prolice District Commander, and police are entitled to appear before the court in relation to any such application.

Revoking or varying an interim or final AVO

An interim AVO is one which applies between court dates whereas a final AVO is put into place for a set period of time at the end of the proceedings.

Any interested party may apply to a court to revoke or vary an AVO, including the defendant, any protected person/s, or police where the application was made for the protection of any person.

A court may revoke or vary an interim or final AVO if satisfied that, in all of the circumstances, it is appropriate to do so.

A variation may involve:

- Reducing or extending the period of the AVO,

- Deleting or amending prohibitions or restrictions, and/or

- Adding prohibitions or restrictions.

A court may refuse to hear an application for revocation or variation if satisfied there has been no change in the circumstances on which the order was based and the application is in the nature of an appeal against the order. Such an application should only therefore be made if there has been a material change or changes in circumstances.

Notice of any application for revocation or variation made by the protected person, or police on behalf of the protected person, must be served personally on the defendant. However, the court may order the extension of an AVO if the application was made before the expiry of the order. Such an extension will cease to have effect after 21 days, unless it is revoked earlier.

Notice of any application for revocation or variation made by the defendant must be served personally on each protected person, unless the court directs otherwise.

Where an application for revocation or variation is made by one protected person is circumstances where there is more than one protected person, any such revocation or variation will only be in respect of the applicant.

A court that varies an interim or final AVO must explain the effect and potential consequences of the change to any party who is present, as well as cause a written explanation of the same to be provided to the defendant and protected person/s.

A copy of the orders must also be provided to the defendant and protected person/s.

Variation of interim or final AVO by deleting child’s name

The name of a protected person who is a child will only be removed from an AVO application if there are good reasons to do so, which may involve absence of threats or violence against or in the presence of the child, a strong and important presence in the child’s life and other matters which make it in the child’s best interests to delete them from the AVO.

Variation of interim or final AVO upon finding of guilt for serious offence

A court may vary an interim or final AVO for the purpose of providing greater protection for the person against whom a serious offence was committed.

Appealing an AVO

There are two main ways to appeal against a decision relating to an AVO application:

-

District Court Appeal

An appeal may be filed in the District Court against the Local Court’s decision to:

- Make an AVO,

- Dismiss an AVO application,

- Revoke or vary an AVO,

- Refuse to revoke or vary an AVO,

- Award legal costs in relation to the AVO proceedings, or

- Refuse to award legal costs in relation to AVO proceedings.

The appeal must be filed within 28 days of the AVO proceedings being finalised, or within three months if the District Court grants leave (permission) to appeal beyond the 28-day period.

Leave to appeal outside 28 days will only be granted if it is in the interests of justice to do so.

An appeal against an AVO made with the consent of the defendant can only made with the leave of the District Court.

-

Local Court annulment application

A defendant who was not present in the Local Court when the AVO was made can file an application in the same court to annul (cancel) the AVO, and essentially re-open the case.

The defendant will need to persuade the court that it is in the interests of justice to adopt this course of action, which will normally require material and submissions establishing that he or she was not aware and could not reasonably have been aware of the court date and place, or was unable to attend court due to a significant medical condition, accident or other occurrence or situation which prevented attendance.

An annulment application will need to be made within two years of the AVO being made, and the prospects of its success will be enhanced where it was made as soon as possible after the defendant was made aware of the order (in the event he or she was not aware) or the circumstances or situation which prevented attendance at court were resolved (in the event such circumstances or events prevented attendance).

Consequences of Breaching an AVO

There are potential consequences for contravening an AVO, as well as other conduct relating to AVOs such as making false statements to obtain an AVO and breaching AVO-related orders.

What criminal offences relate to AVOs?

There are six discrete criminal offences that relate to AVOs and orders that are ancillary to AVOs in New South Wales:

Making a false or misleading APVO application

Making a false or misleading statement in an application for an apprehended personal violence order (APVO) is an offence under section 49A of the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 which carries a maximum penalty of 12 months in prison and/or 10 penalty units (currently $1,100).

To establish the offence, the prosecution must prove beyond reasonable doubt that:

- A person made a statement, whether orally, in a document or in any other way,

- The person did so knowing the statement was false or misleading in a material particular, and

- The statement was made to a judge or court registrar for the purpose of making an application for an APVO.

Knowingly contravening an AVO

Knowingly contravening an apprehended violence order (AVO) is an offence under section 14 of the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 which carries a maximum penalty of two years in prison and/or 50 penalty units (currently $5,500).

To establish the offence, the prosecution must prove beyond reasonable doubt that the defendant:

- Contravened a prohibition or restriction in an AVO against them, and

- Did so knowingly.

A defendant cannot be found guilty of the offence in the following circumstances:

- In the case of an AVO made by a court, the defendant was not in court when the AVO was made and was not validly served with the AVO thereafter,

- In the case of an AVO not made by a court (such as a provisional or ‘telephone’ AVO), the defendant was not validly served with the AVO, or

- The AVO was contravened to attend mediation or comply with a property recovery order.

Knowingly contravening an ADVO with intent

Knowingly contravening an apprehended domestic violence order (ADVO) with intent is an offence under section 14(1A) of the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 which carries a maximum penalty of three years in prison and/or a fine of 100 penalty units (currently $11,000).

To establish the offence, the prosecution must prove beyond reasonable doubt that the defendant:

- Contravened a restriction or prohibition in an ADVO,

- Did so knowingly, and

- Did so with the intention of causing the protected person physical or mental harm, or fear for their own safety or that of another person.

The defendant is considered to have intended to cause physical or mental harm, or fear for safety, if the defendant knew the conduct was likely to cause the harm or fear.

The prosecution is not required to prove that physical or mental harm was in fact caused, or that the protected person actually feared for their or another’s safety.

Persistently contravening an ADVO

Persistently contravening an apprehended domestic violence order (ADVO) is an offence under section 14(1C) of the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 which carries a maximum penalty of five years in prison and/or 150 penalty units (currently $16,500).

To establish the offence, the prosecution must prove beyond reasonable doubt that:

- The defendant contravened a restriction or prohibition in an ADVO,

- The defendant did so knowingly,

- The defendant had, during the 28 days immediately preceding the contravention, knowingly contravened an ADVO relating to the same protected person, or the same ADVO, or another ADVO arising from the same ADVO application, on at least two other occasions, and

- A reasonable person would consider the conduct in the latest contravention likely, in all of the circumstances, to cause the protected person physical or mental harm, or to fear for their safety or that of another person, whether or not the harm or fear was actually caused.

Contravening a property recovery order

Contravening a property recovery order (PRO) is an offence under section 37(6) of the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 which carries a maximum penalty of 50 penalty units (currently $5,500).

To establish the offence, the prosecution must prove beyond reasonable doubt that the defendant:

- Contravened or obstructed a person attempting to comply with a PRO, and

- Did so without a reasonable excuse.

The defendant cannot be found guilty if he or she establishes, ‘on the balance of probabilities’ (it was more likely than not) that there was a reasonable excuse for the contravention or obstruction.

Contravening a Serious Domestic Abuse Prevention Order.

A Serious Domestic Abuse Prevention Order (SDAPO) is a mechanism whereby a court can impose prohibitions, restrictions requirements and other conditions the court considers appropriate – including conditions normally contained in AVOs and even broader conditions relating to residence, employment, movement and contact – to prevent a person from engaging in domestic abuse against family members, former, current or future partners, or anyone in a domestic relationship with the person’s current or former intimate partner/s.

Contravening a Serious Domestic Abuse Prevention Order (SDAPO) is an offence under section 87E of the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 which carries a maximum penalty of five years in prison and/or 300 penalty units (currently $33,000).

To establish the offence, the prosecution must prove beyond reasonable doubt that the defendant:

- Contravened an SDAPO, and

- Did so knowingly.

The defendant cannot be found guilty of the offence unless he or she was served with a copy of the SDAPO or was present in court when it was made

The Local Court can make a SDAPO on the application of police or the DPP against a person who has been convicted of two or more domestic violence-related offences that carry a maximum of seven years imprisonment or more, and the Supreme Court can make the order if the ground for the application is that a person has been involved in serious domestic abuse activity.

To grant such an order, the court must be satisfied ‘on the balance of probabilities’ (that it is more likely than not) that:

- The person against whom the order is being sought is at least 18 years old, and

- During the last 10 years, when the person was at least 16 years old, he or she:

- had been convicted of 2 or more domestic violence offences with a maximum penalty or 7 years imprisonment or more, or

- had been involved in serious domestic abuse activity, and

- There are reasonable grounds to believe the making of the order would prevent the person from engaging in domestic abuse.

The duration of an SDAPO cannot exceed five years from the day it is served. However, the applicant is permitted to make additional applications at any time.

Having an SDAPO can, for all intents and purposes, extend and indeed expand conditions contained in an AVO, and the fact the orders are framed to include a far broader range of persons – including potential future partners – can place onerous obligations well after a person has ‘served their time’.

It is therefore important to consider attending court and opposing the application, setting out the reasons as to why it is being opposed.

What are the legal defences to AVO- related offences?

In addition to having to prove every element (or ingredient) of an AVO-related offence beyond a reasonable doubt, the prosecution must disprove to the same high standard any general legal defence raised by the evidence in the case.

The defendant is entitled to an acquittal (finding of not guilty) if the prosecution is unable to do this.

General legal defences to AVO-related offences include:

Self-defence

Self-defence arises where the defendant believed the contravention was necessary to defend themselves or another person, or to prevent the unlawful deprivation of his or her liberty or that of another person, or to protect his or her property from being taken, destroyed, damaged or interfered with, or to prevent criminal trespass to his or her land, or to remove a person criminally trespassing, and the conduct was a reasonable response to the circumstances as the defendant perceived them at the time.

Duress

Duress is a defence that arises where the contravention occurred due to an imminent threat to the defendant or someone close to the defendant, in circumstances where the threat was continuing and serious enough to justify the conduct.

Necessity

Necessity is a defence that arises where is where the contravention occurred to avoid serious, irreversible consequences to the defendant or someone the defendant was bound to protect, the defendant honestly and reasonably believed they or the other person were in immediate danger and the conduct a reasonable and proportionate response to the danger.

Automatism

Automatism is not a legal defence in the strict sense of the term. However, a state of automatism will render a defendant’s actions involuntary and therefore result in the mental element of an AVO contravention being incapable of establishment.

Automatism is where the contravention occurred as the result of an involuntary act such as one which occurred whilst asleep or otherwise unconscious, concussed, suffering from drug induced psychosis or emotional trauma-associated transient disassociation, or what is commonly referred to as a ‘fit’ such as one brought about by a condition of epilepsy, or any other involuntary conduct.

Mental illness

Mental illness is an offence that arises where the defendant had a cognitive impairment and/or mental impairment at the time of the contravention, did not know the nature or quality of their actions, or did not know the actions were wrong.

Costs Orders in AVO Cases

A court presiding over an AVO case has the power to award professional costs – which include the costs paid for lawyers, disbursements rendered and witness expenses – in certain limited circumstances.

Costs awards may specify a particular sum of money, or that a sum is to be agreed between the parties or be referred for assessment by a cost assessor.

Awarded costs are paid to the court registry before being distributed to the awarded party.

The rules relating to costs awards depend on a range of matters including whether the application for costs is made when the case is adjourned or finalised, whether it relates to an AVO brought privately or by police, as well as the party making the application.

Costs against the police

Costs may be awarded against police who have made an application for an AVO for the protection of a person.

The Supreme Court of NSW has made clear that such an order is only to be made if police have deviated so far from what is reasonably expected of them that a costs order is warranted.

That said, the legislation makes clear that costs may only be awarded against police who have made an application for an apprehended domestic violence order (ADVO) for the protection of a person if the court is satisfied that the applicant officer:

- Knew the application contained a matter that was false or misleading in a material particular, or

- Deviated from the reasonable case management of the proceedings so significantly as to be inexcusable.

In such proceedings, the mere fact the protected person did any of the following does not give rise to the award of costs against the police officer if the application was made in good faith:

- Indicated he or she would not give favourable evidence,

- Indicated he or she did not want the ADVO or had no fears, or

- Failed to attend the hearing or attended and gave unfavourable testimony.

Where there are associated criminal charges, costs may be ordered in favour of the defendant upon the finalisation of the proceedings – whether this is when charges are withdrawn or dismissed after a hearing – where:

- The investigation into the alleged offence was conducted in an unreasonable or improper manner,

- The proceedings were initiated without reasonable cause or in bad faith, or were conducted by the prosecutor in an improper manner,

- The prosecutor unreasonably failed to investigate, or to investigate properly, any relevant matter of which it was aware, or ought reasonably be aware, which suggested the proceedings should not have been brought or the defendant might be not guilty,

- An exceptional circumstance relating to the conduct of the prosecutor makes it just and reasonable to make a costs order.

The amount of costs will be what the judge considers to be just and reasonable in the circumstances.

The State will indemnify police from personally having to pay any costs order, which essentially means costs awarded in favour of the defendant will be paid by the government.

Costs against the person seeking protection

Costs may be ordered against an applicant who is seeking protection by way of a private AVO if the court is satisfied the complaint was frivolous or vexatious.

Costs on adjournment

Costs may be ordered in favour of a party when AVO proceedings are adjourned – whether or not there are associated criminal charges – if the court is satisfied the party seeking costs has incurred additional costs because of the unreasonable conduct or delays of the other party.

Such costs may apply regardless of the ultimate outcome of the proceedings.

The amount of costs may be determined upon adjournment or at the finalisation of the case.

Property Recovery Orders

A property recovery order (PRO) is an order which sets out the rules to enable a defendant or protected person in an application for a provisional, interim or final apprehended domestic violence order (ADVO) to retrieve property that belongs to them.

An application for a PRO can be made by a defendant in an application for an ADVO, an applicant in a private ADVO or a police officer who applies for an ADVO on behalf of a person on whose behalf protection is sought.

A PRO may:

- Direct the occupier of a premises to allow access to the person and any accompanying police in order to retrieve personal property,

- Provide that access at a time or times arranged between the occupier and a police officer,

- Require the person who has left personal property to be accompanied by a police officer when retrieving the property,

- Provide that the person who has left the personal property be accompanied by another specified person, and

- Specify the property to which the order relates.

A PRO does not authorise entry to the subject premises by force.

Nor does the making of a PRO confer rights on a person to take property they do not own or have a legal right to possess, even if the property is specified in the order.

It follows that a person who takes property pursuant to a PRO they know they do not own or are legally entitled to possess may be charged with an offence, such as larceny (a form of stealing or theft).

Additionally, a defendant cannot be found guilty of contravening an AVO for complying with the conditions of a PRO, even if compliance would – on the face of it – be a breach of the orders contained in the AVO.

Case law has found that here is no right to appeal to the District Court against a PRO.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I agree to an AVO without admitting the alleged conduct?

Yes. A defendant can consent, or agree, to a final AVO without admitting to the conduct alleged in the grounds for complaint.

This is done in court and will result in a final AVO being ordered, and the defendant avoiding an AVO hearing.

Can the protected person withdraw an AVO?

A protected person – also known as the complainant – only has the power to withdraw an AVO application that is made privately.

A protected person does not have the power to withdraw an AVO application made on their behalf by police. Only police can withdraw such an application.

Can a protected person be charged with contravening an AVO?

No. The AVO only applies to the defendant. This means a person cannot be charged with contravening an AVO in which they are the protected person.

The law also makes it clear that a person cannot be charged with aiding, abetting, counselling or procuring the contravention of an AVO in which they are the protected person.

How Can We Help?

Our defence lawyers have a thorough understanding of the laws that relate to apprehended violence orders, as well as many years of experience in consistently defending and winning AVO cases.

We can assist you by:

- Evaluating your case;

- Informing you of the rules and how they apply to your case,

- Advising you of the best way forward, and

- Fighting to achieve the optimal outcome.

So, call Sydney Criminal Lawyers today on (02) 9261 8881 and engage specialist defence lawyers with an exceptional track record of having AVOs withdrawn and dismissed in court.

We offer a free first conference for all defendants in AVO cases.

Recent Success Stories

- Assault Occasioning Actual Bodily Harm Charge and AVO Dropped

- Assault Occasioning Actual Bodily Harm Charge and AVO Thrown Out of Court

- All Allegations of Assault (Domestic Violence) Withdrawn and Dismissed

- Assault Charge and Apprehended Domestic Violence Order Dropped

- Not Guilty of Assault, Stalk/Intimidate, Damage Property, AVO and Costs Ordered Against Police

- Yet Another AVO Dismissed and Costs Awarded in Favour of Our Client

- Not Guilty of Assault Charges and AVO after Defended Hearing in Downing Centre Court

- Not Guilty of Aggravated Indecent Assault

- Assault Charges and AVO Thrown Out of Court Despite Testimony of 'Independent' Witness

- AVO Thrown Out of Court and Police Ordered to Pay Our Client's Legal Costs

Recent Articles

- Can a Protected Person Be Charged with Contravening an Apprehended Violence Order?

- Serious Domestic Abuse Prevention Orders in New South Wales

- The Offence of Persistently Contravening an Apprehended Domestic Violence Order in NSW

- The Offence of Knowingly Contravening an Apprehended Domestic Violence Order With Intent in NSW

- How to Vary the Conditions of an Apprehended Violence Order in New South Wales

Our entire firm is exclusively dedicated to criminal law – which makes us true specialists.

Our entire firm is exclusively dedicated to criminal law – which makes us true specialists.